Si Smits: champion of cycles, saloons, and charities

"If you can believe it, I found my community through graffiti on a bathroom wall."

Si Smits was born Sylvester George Smits Jr. in 1945 in Appleton, Wisconsin. He lived on the family farm until leaving for Vietnam at age 20. He doesn’t remember any bullying or name-calling but admits he might have just been oblivious to it happening.

“I remember wearing colored shoestrings on my shoes in high school,” said Si. “I didn’t know I was gay; I just knew I was different. My first inkling was being attracted to a football player whose locker was left of mine. I really admired his body. On the other side of my locker was a cheerleader for the football team. I didn’t really like her, but I saw her all the time. Well, she got pregnant by him – and I was so disappointed that she got him, and I didn’t. That’s when I really understood I was attracted to men.”

In 1966, Si enlisted in the Army and was sent to Vietnam, where he spent the next few years.

“I was in the tent with all the administrative people,” he said, “which included clerks, ministers, assistants, you know. We had these huge mosquito nets over our beds to prevent tropical diseases. One night, a hand appeared under my mosquito net massaging my leg. I thought, well, this is strange, and I shooed it away.”

“A week later, word was spreading around the tent that there was a queer among us,” said Si. “The word was that the only thing that comes from Texas is steers and queers -- and one of the guys in the tent was from Texas. And then he just disappeared. I guess that’s where I really learned, at 21 years old, about gay life. I ‘came out’ to myself but didn’t really come out until I was back in Milwaukee in 1969.”

After coming back to the States, Si worked at the Chicago Army Headquarters on 53rd Street, and then Fort Sheridan, doing administrative work. After being discharged in spring, he enrolled in the fall semester for college, but had some time to kill.

So, he went down to Milwaukee every weekend. His first apartment on 28th Street was only $8/week.

Being seen

Si remembers attending Gay People’s Union meetings for the first time.

“I was working the midnight shift at that time, so I was able to make the 8 p.m. meetings at the Farwell Center,” said Si. “I went to listen, but not really lead. I didn’t consider myself an activist then and I still don’t now. I’m more a person who sits, listens, and contributes. I met so many important people at GPU: Alyn Hess, Eldon Murray, Michael Lisowski, Paul DeMarco, Miriam Ben Shalom.”

Through Gay People’s Union, Si also became one of the most visible gay men of 1973.

“WTMJ4 reached out to GPU asking to interview someone for this special series they were doing,” said Si. “Even though I was a shy person, the act of being seen on TV excited me. I barely thought about it, so I didn’t have time to be scared. In the end, WTMJ4 as fair, honest and respectful. They were actually trying to help the community.”

The series, “Some Call Them Gay,” ran for four nights in September 1973, and featured a balanced look at gay life through social, economic, legal, political, and cultural considerations. Today, the entire series is available for viewing on YouTube.

“It seemed like such a small thing, but it wasn’t small to the people who saw it. I know the series lifted up a lot of people who were in the closet, who had no connections to their community or culture.”

Although GPU effectively disappeared in the mid-80s, the organization still exists on paper today. Si still holds the 501c3 license for Gay People’s Union that was incorporated over 50 years ago. Up until 2015, Michael Lisowski sponsored GPU through his MATA Cable show, The Queer Program. Today, Si sponsors the $25 annual renewal cost.

“GPU did what it was supposed to do,” explained Si. “It brought strength to that first generation of gay liberation. It inspired so many other organizations, many of whom took over GPU functions, and those new organizations splintered off in different directions. The real movers and shakers of the movement died of AIDS, and nobody really rose up to replace them. As a result, GPU didn’t evolve, and it’s time was done.”

Si likened GPU’s disappearance to the demise of the Milwaukee Entertainer’s Club, an incredibly talented production company that toured the state in the 1970s and early 1980s.

“They were one of the greatest things to ever come out of Milwaukee, and they really united our community,” said Si. “And then, even the Entertainer’s Club just fell apart.”

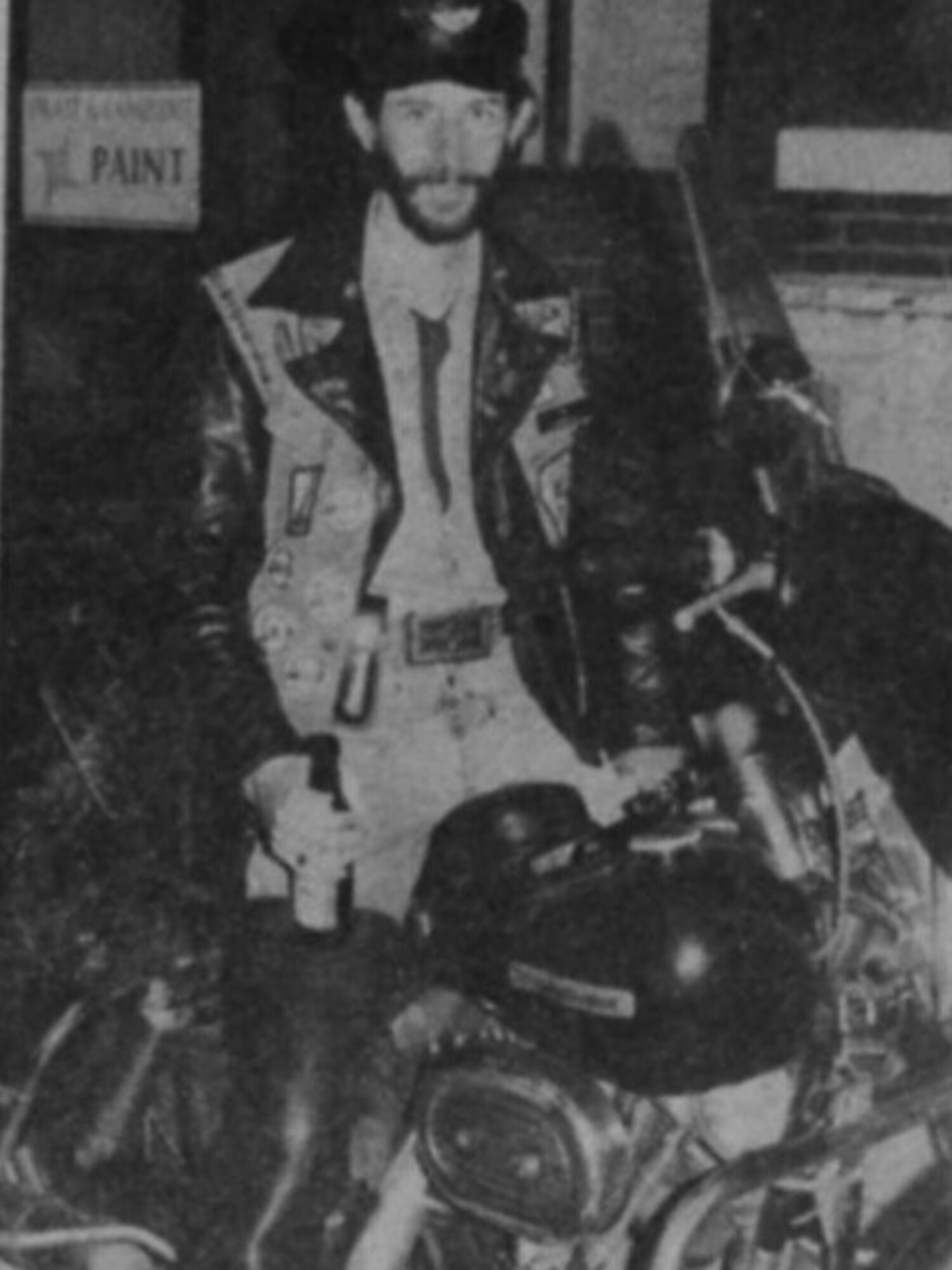

Start your engines

Growing up in rural Wisconsin, Si was fascinated with his neighbor’s motorcycle as he rode around the neighborhood. So, he saved his money and bought his first motorcycle – a Honda 350 – when he was 24 years old.

“I would park it right in front of the Royal Hotel,” said Si. “I was the only person who wore a leather jacket and parked in front of the gay bars at that time. Everyone else parked in back or far away. They didn’t want anyone to see them. I remember going down to Castaways when it would get packed on Friday and Saturday nights. Jimmy Zingale was outside, and he took one look at my leather jacket and said, ‘you can come in, but you have to stay over in that corner.’ He wouldn’t let me in the rest of the bar. I reminded him about this years later when he was my liquor distributor.”

“I met Chuck Renslow a few times, when he was opening up the new Gold Coast location,” said Si. “He took me and my friends into his place and down into the basement. I remember there being lumber everywhere. A few years later, he had the first International Man of Leather contest a few blocks away from the Gold Coast, and we walked over to the event together. Then, I got too busy up here, and I somehow lost touch with him.”

In the early ‘70s, Wreck Room was one of the few places to find out about motorcycle community events. The Leather/Levi crowd really began to organize on a regional basis.

“If you wanted to go to events in Detroit, Minneapolis, St. Louis, you could find them,” said Si. “You’d pay $50 upfront to get free drinks, meals, and a whole lot of sex. My friends and I went to quite a few of these. My friend Joe from Green Bay, who owned a bar, would attend these with me. We talked about it seriously and decided to start something in Milwaukee. There were guys who didn’t want to go to drag shows or dance clubs, who still wanted their own space. Wreck Room already had a strong membership crowd. So why not? That’s how the Silver Stars Club was born.”

Si remembers hanging with the Silver Stars Motorcycle Club at the Shaft (219 S. 2nd St.)

“They’d have a beer bust and a Queen of the Month contest,” said Si. “Whoever was wearing this quilt, like a cape, was the Queen.”

Silver Stars continued for many years, until a fateful Thanksgiving party at the Astor Hotel.

“Bob Mannix came up for the event,” said Si. “He was connected with a popular Chicago leather store, and he brought a boy with him who was a leather drag queen. I was chastised for bringing not just a drag queen, but an out-of-town drag queen, into this space. So, I was kicked out of Silver Stars – the club that I started – in 1976. It continued for a short time after I left.”

“We created a new motorcycle club afterwards called the Castaways,” said Si. “The logic was that since I was cast out, we’ll call it Castaways. Some people went off and started the Argonauts in Green Bay around that same time.”

In 1984, Si launched his third motorcycle club, the Beertown Badgers, which ran until 1995.

The Boot Camp is born

“I was living on 9th and Lapham in winter 1984,” said Si, “and I wanted out of that neighborhood. My nice Harley-Davidson had been stolen that summer, and on New Year’s Eve, my Bronco truck had been broken into. I was just about to go out to the bars to celebrate. By the time the police came, my truck was gone! I thought, time to go. As I was looking for places to move, I was also thinking, what am I going to do next? Spend the rest of my years at Wreck Room? If so, I should open my own bar."

"And then I found a bar for sale in the newspaper. It was an old Mom & Pop tavern, run by a grandmother, and the owner worked at Barry Trucking Company across the street. It was only open 2-3 hours a day for the truck drivers, and it wasn’t making any money at all. They weren’t even open at night."

“The price point was perfect, and I thought, OK, I’m going into the bar business. Instead of sitting in a bar all night long, I’m going to own my own bar and sit in my own bar.”

“I’d actually dreamed of owning a bar since childhood,” said Si. “I heard about this legendary Florida club called the Copa and thought it would be fun to run a club of my own.”

“The thing is, I didn’t warn Wayne in advance,” said Si. “But I wasn’t trying to take away his business, either. I had my own following. I had been out in the bars for a long time and knew a lot of people – enough people to make a living with my own bar. For the first few years, I was only open from 8-2pm so we only needed one shift of workers. I was still working at NML those first two years.”

“Wayne had more going for him: softball leagues, bowling leagues, the Wreck Room Classic. He had all these structures I didn’t have. My customers were older, didn’t care about sports, and weren’t exactly joiners.”

When Boot Camp Saloon (209 E. National Ave.) opened in 1984, there was an explosion of gay bars happening in Milwaukee. Three new lesbian bars opened that same year. The state was riding high on its reputation as the Gay Rights State, and the specter of the AIDS crisis was still years ahead.

“I ran a pretty tight ship,” said Si. “At the first sign of trouble, I wanted you out, because I wasn’t going to fight with you. I wasn’t big or strong enough to fight with people. But it was a bad misconception that we didn’t allow women or drag queens in the bar. Four lesbians who hung out with the Silver Star Motorcycle Club were regulars at the bar. They later formed the Forkers Club of their own. They even held a Women’s Leather Night at Boot Camp.”

“Whenever women or drag queens showed up, the other customers complained, this is a gay man’s space, a butch space, a leather space. It’s not a women’s bar or a drag bar or a straight bar. The business welcomed everyone, but the clientele often got very territorial.”

“I never really felt like I fit in with the other bar owners,” said Si. “I spent a lot of time with Wayne Bernhagen before I opened a bar, so maybe we were tight. John Clayton once tried to pick me up, but that sure didn’t work.”

“I was the worst bar owner in the city, because I never communicated with people,” said Si. “People saw me as protective, but mysterious, even stand-offish. I just don’t have the outgoing personality that a bar owner should have. This has been a problem throughout my life. I was an only child, raised on a farm, and grew up isolated and bashful. I still can’t walk up to people in public and say hi, because I’m aware that I’m interrupting something.”

Si worked hard to protect the space he’d created, as local police often sought reasons to shut it down.

“Boot Camp was raided several times,” said Si. “Police would claim they saw people in the bar after hours, but they’d come in and never find anyone. They couldn’t find any tracks, they couldn’t find any cars, they couldn’t find any evidence of people in the space. They’d see reflections in the mirrors and mistake them for real people.”

“When we’d show movies in the backroom, detectives would come in, have drinks, and watch for over an hour. Eventually, someone would touch someone else, and BAM! That's all they needed. And then, they’d hit us with these huge tickets and try to talk us into plea bargaining."

"Well, I decided I could play their game better than they did. I was asked to take plea bargains because it would take hours to locate the officers and bring them to the courtroom. I said, I’ll wait. I wanted my $500 worth of justice. When the detectives showed up, I had my chance to ask them questions, and ultimately the judge reduced the fines. I wasn’t going to pay the fee and lose my license renewal. I wanted justice. They were harassing me, my staff, and the bar, and I was going to play the game. This happened 5-7 times over the years.”

Still, Si has great memories of the golden age of Boot Camp when people would park once and hit 4-5 bars in one night.

“La Cage, Your Place, Triangle, Boot Camp…those were the days! The neighborhood had a really strong pulse to it.”

Caring for a community in crisis

Si remembers the community coming together to raise funds for the AIDS crisis.

“Being a bar owner, we were always asked for door prizes and donations,” said Si. “And I remember those asks getting increasingly aggressive that first year we were open. There was always something to raise money for: Gay People’s Union, BESTD Clinic, Milwaukee AIDS Project. I didn’t want to keep asking my customers to donate, because they were getting hit up for money at every turn, 20-30 times a year.”

“Forty years ago, the community looked at bar owners as its pillars,” said Si. “We didn’t have a lot of organizations; we didn’t have anywhere to look for guidance or leadership. If you were a bar owner, you were on stage all the time, and people expected you to be the leader. So, I knew I had to do something.”

“Finally, I decided I should start my own foundation so these donations could be tax exempt,” said Si. “I wanted to make things accessible and fair for everyone. We were trying to help the Community Center establish themselves back then, so we stared as the G/L Community Center Trust Fund. Over the years, as we achieved our goals, we dropped the Community Center name, then the Trust, and now we’re just the G/L Community Fund.”

“In those first years of fundraising, I was so grateful to work with Bob Schmidt at M&M Club. We hosted many holiday fundraising dinners upstairs at M&M Club. There was no charge for the room, the bartenders donated their time, and we received so many donations for the silent auction. We started the Community Fund with that money. And we had a lot of competitors, including Cream City Foundation, for those donations.”\

Today, the Gay and Lesbian Community Fund supports over a dozen small local non-profits and community causes, including the Wisconsin LGBTQ History Project.

Changing times

By 1995, the Wreck Room was approaching the end of its 24-year run. AIDS claimed Wayne Bernhagen (1943-1987) and Bill Kindt was getting older and tired of running the business in a rapidly changing Third Ward. A year later, it was gone, and with it, an entire way of life.

With the Wreck Room gone, Boot Camp was the only bar serving the Levi & Leather crowd in town. The Milwaukee Eagle opened with great expectations in November 1997, but it barely lasted two years. To this day, there are still rumors swirling about its short-lived run.

“I had a customer from Shorewood who said he was the owner,” said Si, “but he was just a big talker, and so I dismissed him. Later, I found out it was owned by some straight Middle Eastern men who were just taking our dollars. They weren’t even gay. They were just ripping us off. That would explain the odd vibe of the bar. It always felt fake and uncomfortable.”

Si remembers Serge and Jerry, owners of Kruz, meeting at Boot Camp. When Kruz opened in 2006, they’d meet for cocktails once a month – and exchange beer glasses. Kruz was a perfect complement to Boot Camp, not a competitor, and many customers would take a circle tour between the bars every weekend.

“It makes me feel good when people say, ‘I met my boyfriend at your bar,” said Si. “That’s one of the things I feel best about. I created a place where those lifelong connections were born.”

Sadly, a catastrophic fire consumed Boot Camp in May 2011. The business did not reopen, and over a decade later, nothing has been built on its landmark site.

What will tomorrow bring?

After five decades as a local fundraiser and business owner, Si has some real concerns about our future.

“We’re in a better place than we were 50 years ago, but we can’t give up. The pendulum swings back and forth,” he said, “and we should be afraid of what our enemies want to do. If they convince enough people to suppress us, those old laws could come back.”

“We need more movers and shakers to step up,” said Si. “In my day, we had Eldon Murray and Alyn Hess. I don’t see a lot of people elevating the community the way they did. I don’t see a lot of real leadership.”

“I often think about John Clayton, who took in all these runaway boys,” said Si. “He gave them a place to eat, sleep, work, things to do that kept them off the street. He really turned around a lot of lives that were heading the wrong way. And yet, there was all this gossip about him, and the police harassed him for years, and tried to shut C’est La Vie down. They don’t even know how many young men he helped. Where would these men be today without him?”

“I feel gay bars are still necessary,” said Si, “especially for people with family problems, religious conflicts, and other issues they’re struggling with. I think of all the people who come to PrideFest. They come to the big city, and they’re in heaven, because there’s all this fun between the gay bars and the parade. This is the one weekend a year they can really feel free.”

“Pride is still needed, too. We have to continue with it no matter what. If we do away with our pride traditions, we will lose a lot. I remember being on the parade committee in 2004, when it was decided bar owners weren’t welcome at PrideFest. We took over the Milwaukee Pride Parade with the owners of OutBound Magazine. Jim, James, and I worked really hard to make it successful on its own. Today, the parade is the Sunday headliner of PrideFest weekend.”

Today, Si hangs out at Kruz, which has a modern-day “Boot Camp vibe,” and Harbor Room, where he sees a lot of people from his bar.

“They’re fading away fast,” said Si, “and there’s not too many of them going out anymore. The whole Leather & Levi scene is dying. It’s not out in the open like it was in the old days. How often do you see people in leather chaps in public? Is there even still a place in the world for leather bars? I’d like to see it last, but I don’t think it will happen.”

“There’s not much room for leather anymore.”

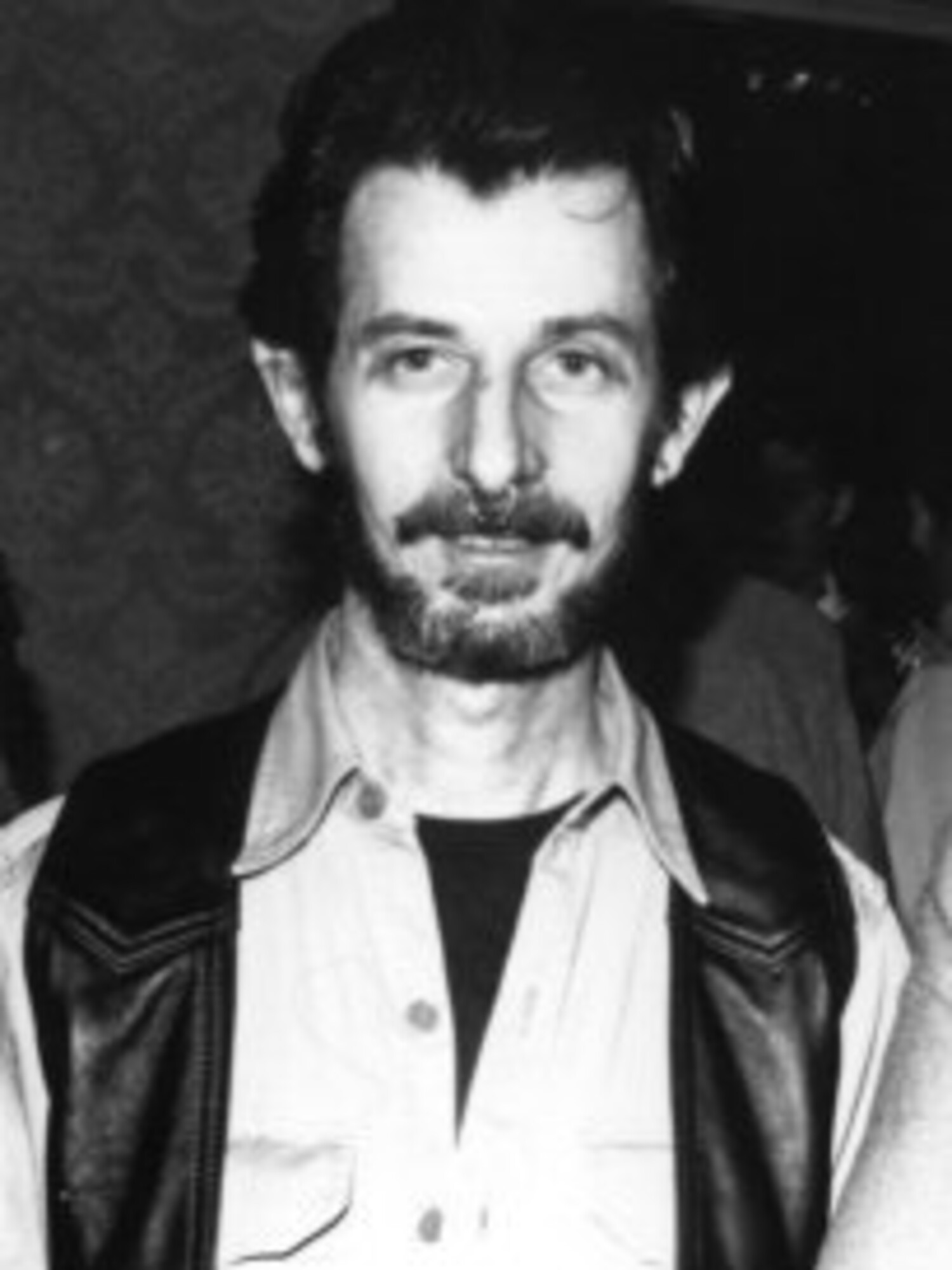

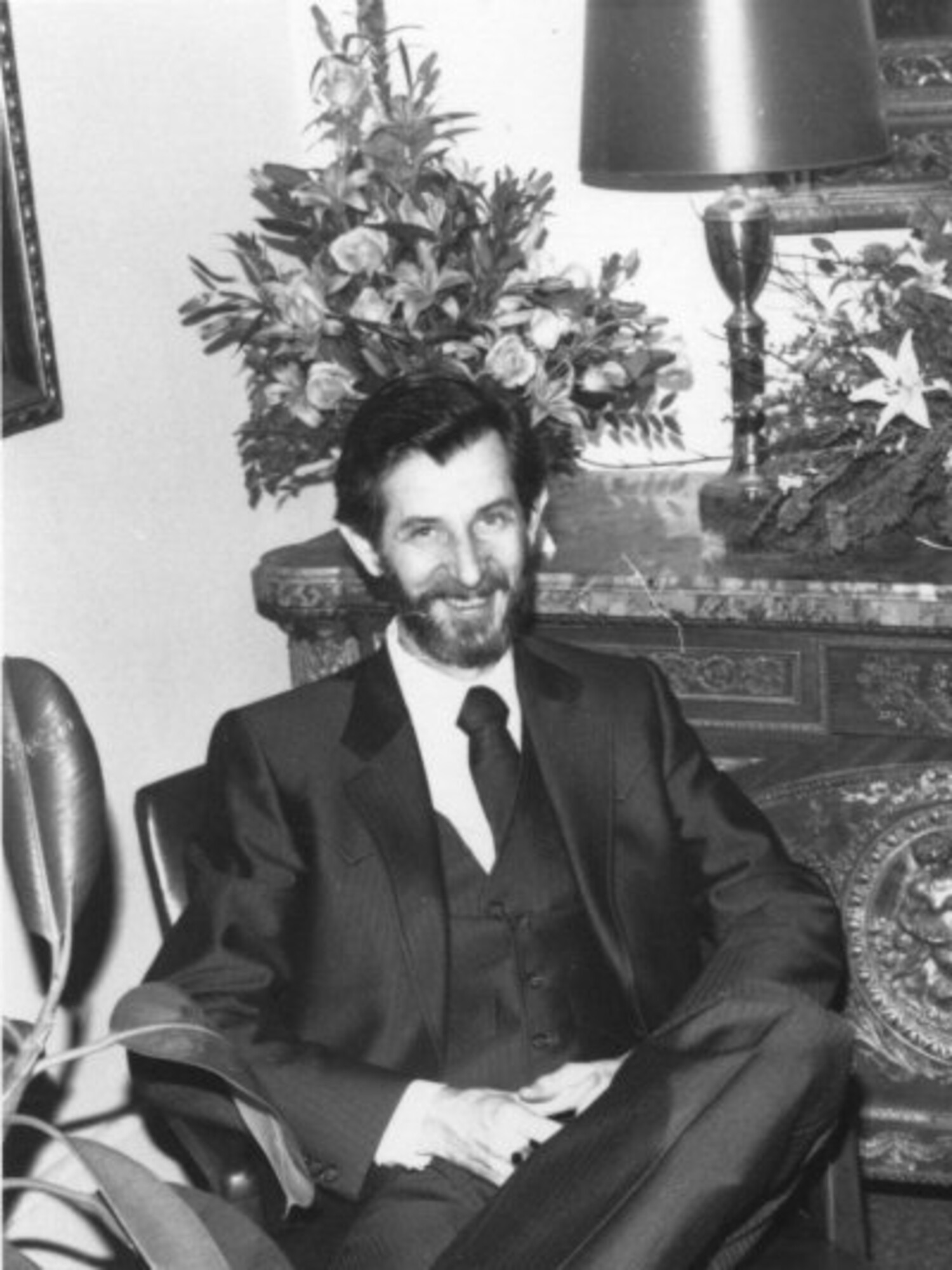

Si at the Boot Camp

Si at the Boot Camp

Surviving members of Gay People's Union, 2021

Surviving members of Gay People's Union, 2021

Si Smits and Don Schwamb, 2024

Si Smits and Don Schwamb, 2024

recent blog posts

April 06, 2025 | Michail Takach

Camille Farrington & Vicki Shaffer: standing up for students

March 31, 2025 | Amy Luettgen

March 29, 2025 | Michail Takach

The concept for this web site was envisioned by Don Schwamb in 2003, and over the next 15 years, he was the sole researcher, programmer and primary contributor, bearing all costs for hosting the web site personally.