Patrick Bergen: aces for the win

"I really want people to understand they're not broken."

Patrick was born and raised in Germantown, Wisconsin to a pretty traditional Catholic family. As a teenager growing up in the ‘90s and ‘00s, he was heavily influenced by the emo and pop punk scenes.

In gym class, he experienced “locker room talk,” but mostly dismissed it.

“I always thought it was a a joke,” said Patrick, “they don’t really think about this stuff, they don’t really want to do these things. I didn’t understand why people acted like ‘saving themselves for marriage’ would be a nearly impossible task. To me, it seemed pretty easy.”

“I remember friends talking about Megan Fox or Keira Knightley as their celebrity crushes,” said Patrick, “and for me, it was more of a ‘this person seems cool and I’d like to hang out with them.’ When asked, I would say my crush was Hayley Williams of Paramore, because she seemed cool and artsy. I didn’t understand how there could be anything deeper.”

Visibility is power

“I started following people on social media, and later, started sharing my story online. I found AVEN (Asexuality Visibility & Education Network,) a central online hub connecting ace people all over the world. I connected with a handful of creators, and now I’m a content creator myself. I’ve launched outreach on YouTube and TikTok to share our message. I’m trying to use all of my gifts to educate in a relatable way.”

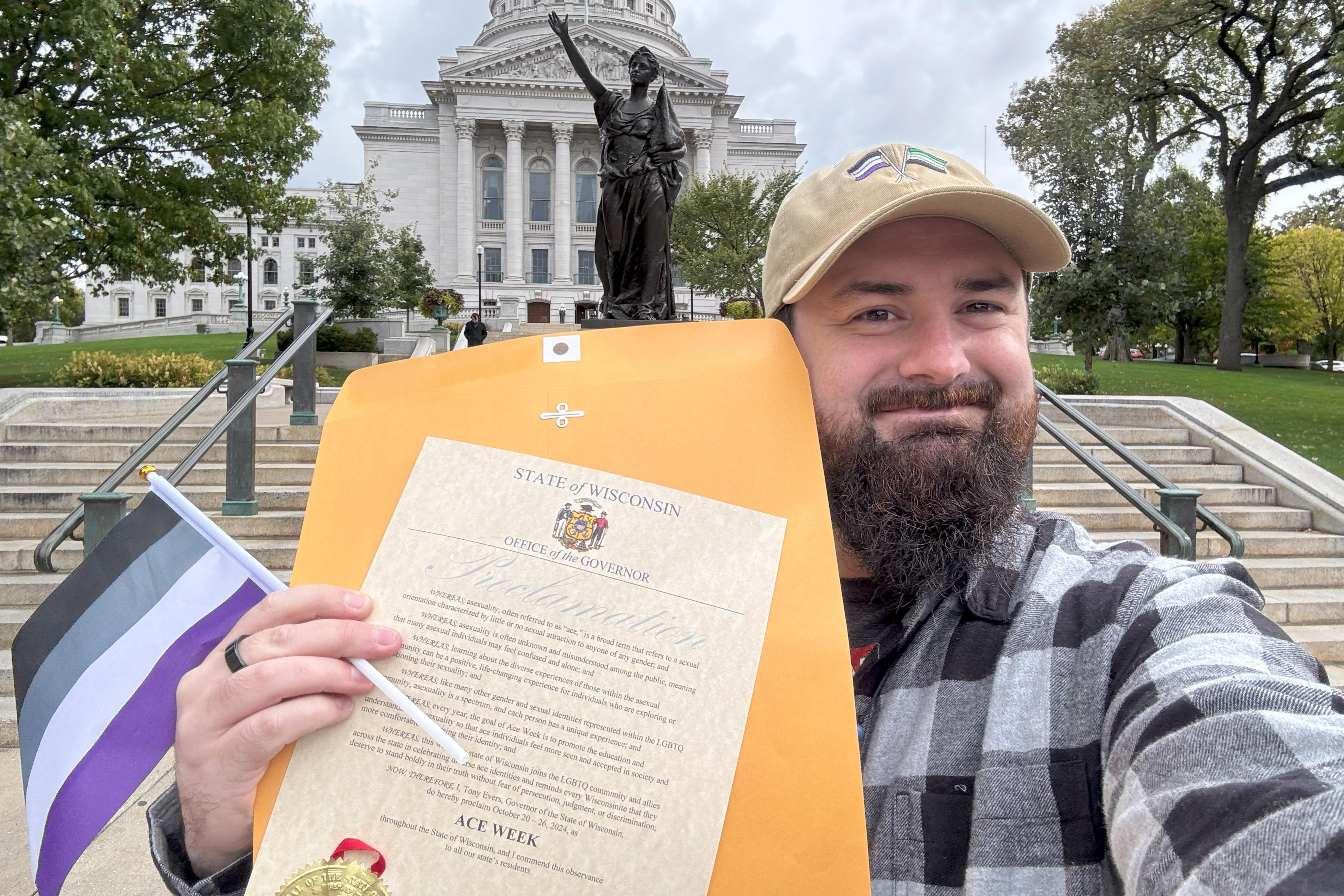

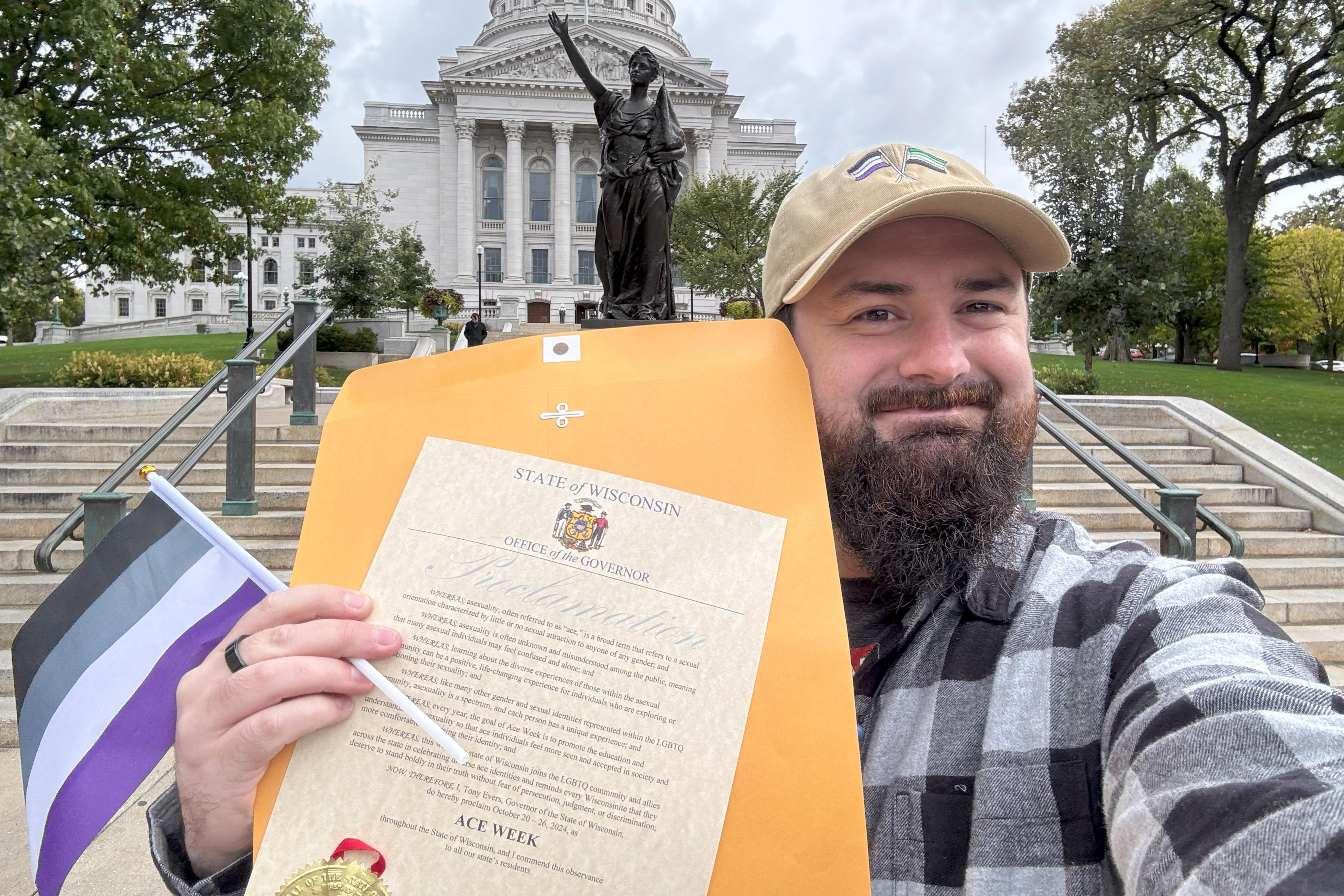

“A lot of aces relate to feeling broken, before they know what is actually going on. I really wanted people to understand that they were not broken. I founded Fluently Aspec as my passion project. And I’ve been advocating for Wisconsin Ace Week since 2022. I knew other states had observed Ace Weeks – Pennsylvania, Washington, Illinois, Michigan -- and I felt Wisconsin needed their own. Wisconsin has been a front-runner in queer legislation, and a vital first step towards legislation is recognition and understanding.”

“So, I did all the research, submitted the proclamation, and now it’s become a tradition in Wisconsin for a third year. The goal of Ace Week is to promote the education and understanding of asexuality so that ace individuals feel more seen and accepted in society and more comfortable expressing their identity.”

“I met Gentle Giant Ace, a wonderful creator, who organized Ace Week in Pennsylvania. We collaborated on a YouTube video that sends a call to action to ace people everywhere. Let’s get 10 states to recognize Ace Week this year. Next year, maybe it’s 15 or 20. We want to take these proclamations and make them visible to elected officials.”

“The A is not always seen, even by allies and advocates. They stop at the “I” in LGBTQIA. This is wonderful, because intersex individuals get recognized, but it’s at the expense of the “A.” I wonder if that’s because people mistake A for ally, when A actually stands for the A-spectrum of asexual, aromantic, and agender. Another word for this group is ‘aspec.’”

Why does it matter? When the “A” is invisible, legislation doesn’t include them. For example, the acronym used in this year’s Title IX updates stop at the I. While the word “asexual” appears once, the A appears nowhere: it’s all about the LGBTQI.

“As an educator myself, that’s concerning,” said Patrick.

Another area is marriage. There are still states where marriage is not legally binding until it’s been consummated.

“Who’s checking that? Why is this still on the books?” asked Patrick. “Marriages should be valid and recognized for being a marriage without sexual activity required. I’d also like to see a ban on conversion therapy. Many aces are highly susceptible to this treatment. They feel they are broken and that only a procedure can fix them.”

“This, too, is wrong.”

Patrick and friends

Patrick and friends

Patrick and friends

Patrick and friends

Patrick and friends

Patrick and friends

Myths vs. facts

Because society is often so sex-focused, people are raised to relate and respond to others through attraction. When you spend your whole life ruled by attraction to many, it can be hard to comprehend that others exist who don’t experience sexual attraction to anyone at all.

“Non-ace people just can’t wrap their minds around that absence,” said Patrick. “We do have a term for this, allonormative, the expectation that everyone has sexual and romantic attraction. Whatever direction it may point, everyone has it, right? Wrong, but aspec individuals are still constantly bombarded with this.”

“It’s okay if you don’t experience the same kind of attraction as other people,” said Patrick. “There’s a whole spectrum of identities and we call them micro-labels. An individual might experience attraction only under certain circumstances. For example, aceflux is someone who experiences fluctuations in their sexual attraction to individuals or groups. It’s not constant: it can stop, it can intensify, it can drop off. Another one is demisexual, where sexual attraction only forms when a strong emotional bond has been established.”

“Remember that relationships can look however you want them to look, depending on what you’re looking for yourself,” said Patrick. “Someone out there is looking for the exact same thing. Communicate, compromise, and you can make it work.”

What are some of the myths that ace people face?

“I’ve been told that aspec identity is a medical disorder, such as a lack of testosterone,” said Patrick. “I’ve been told that it’s a mental disorder – maybe a trauma response of some sort. There’s a myth that asexual people are just ‘late bloomers.’ There’s a myth that ace is a ‘white thing.’ But these could not be more wrong.”

“Ace people are often stereotyped as emotionless, cold, or prudish,” said Patrick. “And there’s also this myth that we never have sex. There’s actually a number of ace people who do have sex with their partners. Asexuality is not about NOT having sex. It’s not about the action, it’s about the attraction. That’s the key component.”

“Some of my YouTube videos have really gained traction, and the majority of comments are very negative,” said Patrick. “There’s a religious angle, a science angle, that people like to try to spin. People say we’re just looking for attention. People try to body shame us – comments like, ‘don’t worry, you wouldn’t be getting any action anyway.’

Expressing the A

Up against these challenges, where – if anywhere – can ace people find positive representation in the world?

“Believe it or not, there’s actually been quite a few of them lately,” said Patrick. “Isaac on Heartstopper is canonically aromantic and asexual. That’s been confirmed on the show, where he actually said it. Tori is asexual in the books, but she hasn’t come out yet on the show. Alice Oseman, the creator of Heartstopper, is asexual and aromantic herself. We’ve had Gwenpool in Marvel Comics, who came out as ace not long ago. Alastor, on the animated series Hazbin Hotel, is an increasingly popular ace character. And another really positive example is Todd Chavez of Bojack Horseman. He’s one of the most popular icons of the ace community.”

“While I can name a handful of examples, there is still very little representation. Most aces would probably name these exact same characters, since we have so little to choose from.”

“Sometimes, a character’s asexual identity is erased when moving between mediums. Jughead, a character from Archie Comics, was canonically ace until he appeared on the TV series Riverdale. In other cases, the media gets it wrong: the show Sex Education portrayed asexuality as an avoidance or hatred of sex. The showrunners ignored their own consultants’ recommendations, which they didn’t find out until the series aired.”

“There are many ways to be asexual, and it’s not gender-specific or culture-specific. One of the most well-known aces in the world is Yasmin Benoit. She’s a Black, twentysomething lingerie model from the United Kingdom. That’s not the image most people would have of an ace person. And she’s created a campaign #ThisIsWhatAsexualityLooksLike to challenge those notions. There’s also an Instagram page that features the wonderful diversity of the ace community. I’ve been featured on it myself.”

“The ace community often uses dragons and unicorns as symbols,” said Patrick. “This is a clap-back at the misconception that asexuality is a myth – like dragons and unicorns. Another symbol is space itself, for the vast, open, endless nothingness – occupying the space where there is no pull in any direction, like how we experience little to no pull of sexual attraction. And perhaps our most confusing symbol is garlic bread. This seemed to start as a joke that garlic bread is better than sex, and over time it stuck, so we don’t question it much anymore.”

In closing, Patrick invites everyone to visit his Fluently Aspec channels on YouTube and TikTok for more information. And, if you’re questioning your own place on the spectrum, know you will find support within the community.

“Cake is probably the most meaningful symbol for ace people. Members share the cake emoji, or a picture of cake, when people are introducing themselves on AVEN. So, I’d like to offer cake to anyone who might be aspec themselves. Come on in, grab a slice, you’re one of us!”

Patrick in Seattle

Patrick in Seattle

recent blog posts

December 17, 2025 | Michail Takach

December 16, 2025 | Michail Takach

December 01, 2025 | Dan Fons

The concept for this web site was envisioned by Don Schwamb in 2003, and over the next 15 years, he was the sole researcher, programmer and primary contributor, bearing all costs for hosting the web site personally.