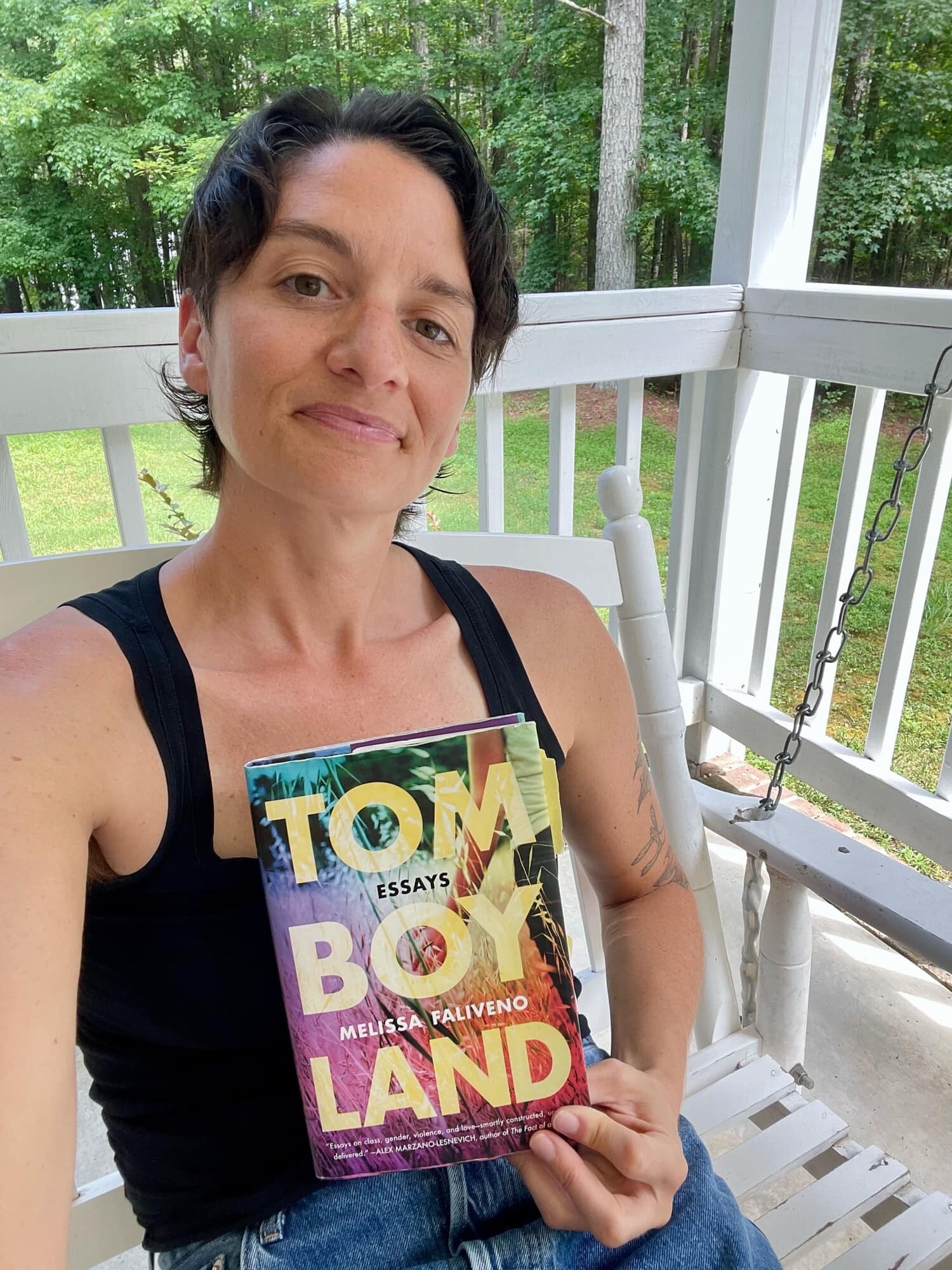

Melissa Faliveno: piecing together the puzzle

“Writing is where I do my figuring out of my own life and my experiences. It feels so right to me that Tomboyland would be how I would come out. "

Melissa Faliveno, an assistant professor of English and creative writing at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, has had a fascinating journey of self-discovery and identity exploration.

Born in 1983 in Madison, Wisconsin, Melissa grew up in Mount Horeb as a tomboy, identifying more with the boys in her life and feeling frustrated by the traditional expectations placed on girls. As a teenager, they conformed more to societal norms of femininity, but still struggled with their sense of gender and sexuality.

As an adult, Melissa identifies as genderqueer and uses both she and they pronouns.

In terms of sexuality and gender identity, she started to understand it in college. She didn't really conceive of themselves as queer until then, but looking back, they could see the queer puzzle pieces that were always there. They have spent their life seeing and arranging those pieces to fit together comfortably and snugly.

When Melissa moved to New York and attended Sarah Lawrence, which has historically been a very LGBTQ-friendly school, she met a diverse group of queer individuals from across the country and the world.

She had already used bisexual to describe their sexuality but a friend at Sarah Lawrence used the term genderqueer to describe them. At first, Melissa did not think of themselves as genderqueer but their viewpoint changed as they thought about their gender identity more deeply.

“At first I was like, I’m not genderqueer. And then I started thinking about that term and I was like, again, oh actually that’s exactly it. I’m not eschewing womanhood. I’m not a man. I loved that genderqueer was sort of ambiguous, you know, not a male or female definitive term.”

As she started publishing her work, and publicly identifying as a queer writer, Melissa became more involved in LGBTQ organizations and events. She started receiving interview requests from LGBTQ organizations and invitations to readings and events across the country, including PFLAG chapter meetings in their own hometown. Their work with PFLAG has been particularly impactful.

“I have had the opportunity to engage with high school students at PFLAG chapter meetings and have witnessed their excitement about writing and expressing themselves. It's been a powerful and rewarding experience.”

Melissa's book, Tomboyland, was a way to come out to many friends and family, including her parents. It wasn’t as though she was hiding her identity, but there had never been a specific coming out talk with anyone. Through Melissa's life, writing has helped her understand herself and better communicate their experience, so it just made sense that the entire tale of who they are would be released in written form. Sometimes the complexity felt too hard to explain in person and they did not always feel comfortable talking about themselves.

Melissa has reflected that it might be a rural Midwestern quality, or maybe a rural quality generally, to not always speak out loud their deepest truths.

“Growing up in the Midwest we’re not having conversations about identity," said Melissa. "It’s just not something that I had access to, felt like I had language for, or spent any time thinking about. That is, until I was really confronted with people who were talking very loudly about it, and owning themselves and their identities really unabashedly.”

Melissa’s parents are very supportive of her. While Melissa is not certain her parents always understand everything, they alway show up enthusiastically. Melissa proudly states that her Dad is her number-one hype man.

“My Dad, the Italian Catholic from New Jersey and once very conservative, is now shopping at A Room of One’s Own all the time and reading James Baldwin.”

Melissa admits there have been some challenges along the way. She often gets misgendered, and has had a handful of scary run-ins with strangers. But much of the negativity she’s experienced has come from within the LGBTQ community, with people questioning the validity of her bisexuality. Melissa has found it particularly difficult when queer women have suggested she’s an imposter, or able to “pass” as straight, as she has been in a relationship with a man for the past 13 years.

“I don’t consider myself in a straight relationship because I am not straight," said Melissa. "It sometimes feels as though queer folks consider my identity a disappointment or a betrayal. It feels far more hurtful because I feel like this is my community or should be. And I have felt very much outside of it or not queer enough. Sometimes it has made me want to kind of hide and not talk about it and not claim it. It starts to needle at your sense of ownership.”

After a long career in editing and publishing, Melissa recently made a career shift and is now a professor working solely with undergraduates. She remembers being their age, around 18-22, that transformative time of life when she was trying to figure out so many things about herself. She is often the first openly bisexual and genderqueer professor most students have ever had.

“I think I can be a mentor to them in that way," said Melissa. "I have a big progress flag on my office wall, and my bi pin on my board, a sticker on my door that says 'y’all means everyone,' which is a super important thing for young people to see, especially in a state like North Carolina. So many of my students are bisexual, and it’s amazing to me."

"I often help them through hard stuff, well beyond the classroom, and hope I can show them that being bisexual and being queer holds so much possibility, and that life can get really good. I can show them it can and does get so much better.”

Melissa Faliveno

Melissa Faliveno

recent blog posts

December 17, 2025 | Michail Takach

December 16, 2025 | Michail Takach

December 01, 2025 | Dan Fons

The concept for this web site was envisioned by Don Schwamb in 2003, and over the next 15 years, he was the sole researcher, programmer and primary contributor, bearing all costs for hosting the web site personally.