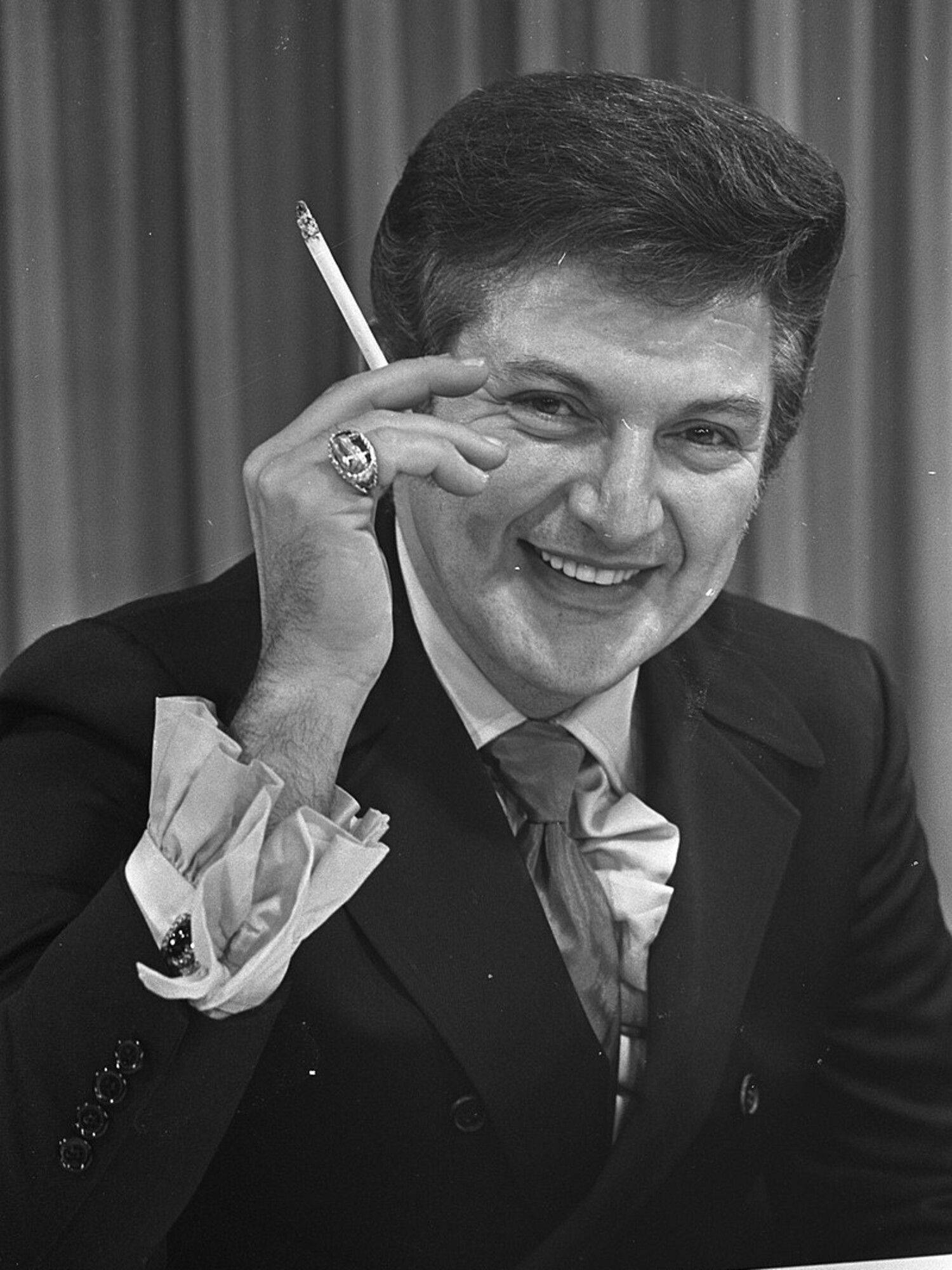

Liberace: the spark that made Milwaukee spectacular

"There's no such thing as too much glitter."

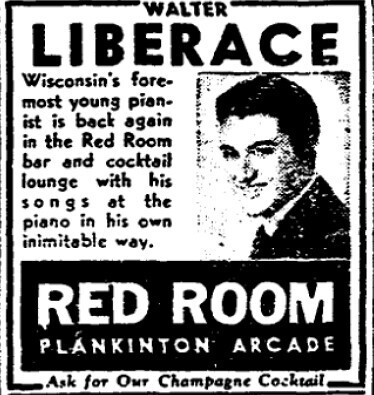

Walter Liberace was born May 16, 1919 in West Allis and grew up in nearby West Milwaukee. His mother’s family was Polish; his father’s family was Italian. Growing up, he and his three siblings were surrounded by music.

After suffering childhood pneumonia, Liberace was always a smaller, thinner and “sickly” child. He experienced bullying from the first day of school onward. As he practiced piano, neighborhood children would come to his window and yell “sissy.”

As a teenager, he nearly lost his arm due to blood poisoning. After a specialist called for amputation, Liberace’s mother said “My son is a pianist. You will save his hand.” The specialist said “we’ll be lucky to save his arm.”

She hesitated for a second and said, again, “Let’s go home, son. You will keep your hand.” Through a combination of strong spiritual faith and unidentified Old World recipes, she healed the poisoning completely.

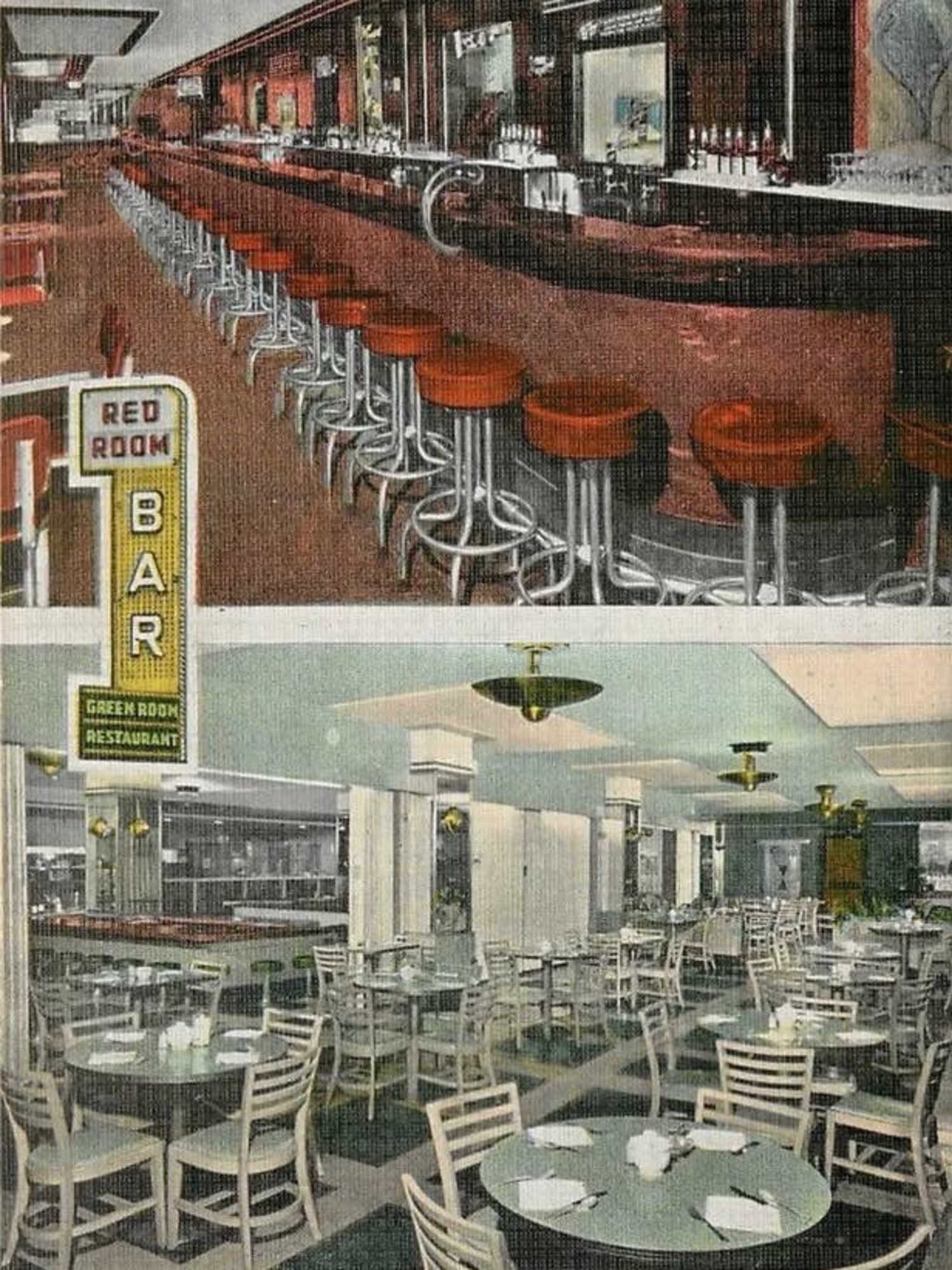

By 1958, the Plankinton Arcade was again feeling old-fashioned and out of favor.

After World War II, people just weren’t coming downtown for entertainment anymore. Attempts to modernize the Green Room as the “Buffet of Plenty” were ambitious but impractical. The Red Room got a facelift, but it was barely noticed as its former regulars now only came once a month – or less.

Downtown was in real trouble. On January 31, 1960, the Plankinton Arcade declared bankruptcy in federal court, resulting in the closing of the Red Room, Buffet of Plenty, Arcade Driving School, bowling alley, billiards hall, and news shop.

The Plankinton Arcade would spend the next 20 years nearly abandoned until the creation of Grand Avenue Mall in 1982.

In 1963, Liberace reinvented himself as “Mr. Showmanship,” investing heavily in glitz, glamour, furs, feathers, and costumes as he toured London, Las Vegas and the world. While he considered himself a one-man Disneyland, his shows took on the gaudy look and gimmicky feel of a big-budget drag show.

Liberace was the first gay person many Baby Boomers ever saw on TV – and some, like Elton John, immediately idolized him.

In 1976, the Liberace Foundation for Creative and Performing Arts opened in Las Vegas with a $4 million donation from Liberace. Liberace Plaza opened at the intersection of Tropicana and Spencer, containing both the Liberace Museum and Tivoli Gardens (a restaurant designed by Liberace.) Three years later, the museum relocated to a complex in Paradise, Nevada, with his brother George serving as director. With a half-million visitors each year, the museum became the third most-visited attraction in Nevada.

After earning two Emmy Awards, six gold albums, two stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, countless TV and movie appearances, and 56 sold-out shows at Radio City Music Hall over an exhausting five decade career, Liberace faced a challenge not even he could glamorize. He was secretly diagnosed as HIV positive in August 1985.

He kept his diagnosis a secret, despite visible symptoms, and refused medical treatment. Even after his death on February 4, 1987, the cause was deliberately obscured, with some sources claiming emphysema, heart disease and/or anemia from a fad diet.

Liberace is entombed at Forest Lawn Cemetery in Los Angeles. Seven years after his death, he received a Star on the Palm Spring Walk of Stars.

Liberace's death sparked tremendous interest in his museum, which tripled in size in 1988 and expanded yet again in 2002. Proceeds from the museum allowed the Liberace Foundation to create over $6 million in music scholarships. From 1993 to 2008, a "Play-A-Like" Competition celebrated Liberace's birthday.

With attendance dwindling, museum leaders announced a move to the Las Vegas Strip. Instead, the museum closed "indefinitely, but not forever" on October 17, 2010. It has never reopened.

The Liberace Foundation is still operating in Las Vegas and still manages the full collection, which has been shown at various exhibits over the years. In 2014, the museum's colorful signage was donated to the Neon Museum. The Liberace Garage opened in 2016, featuring eight Liberace-owned vehicles, a piano, and some of his stage costumes.

recent blog posts

April 06, 2025 | Michail Takach

Camille Farrington & Vicki Shaffer: standing up for students

March 31, 2025 | Amy Luettgen

March 29, 2025 | Michail Takach

The concept for this web site was envisioned by Don Schwamb in 2003, and over the next 15 years, he was the sole researcher, programmer and primary contributor, bearing all costs for hosting the web site personally.