Les Petites Bon Bons: the surprise in your Cracker Jacks

With one year of the Stonewall Uprising of June 28, 1969, more than two hundred gay organizations formed around the United States.

“Some were moderate, some radical, some social, and some nonsensical,” wrote reporter Neil D. Rosenberg in the February 29, 1972, Milwaukee Journal.

Les Petites Bon Bons checked all the boxes.

In fall 1971, Jerry Dreva (1945-1997) and Bobby Lambert (1948-,) residents of South Milwaukee and “veterans of a slightly stale, local civil rights / anti-war / gay lib counterculture,” formed a queer collective of revolutionary guerrillas. Les Petites Bonbons evolved out of local gay activism (Gay Liberation Front, Radical Queens, and New Gay Underground) to become socially and culturally influential on a national level.

Most of the original Bon Bons were disillusioned queer youth from Cudahy, younger than Bobby and Jerry, but no less radical in spirit.

“I was 12 years old, and people somehow just knew I was different,” said Dick Varga. “So, I leaned in towards people like myself, who were different, and we melded into a group.”

“The funny thing is, we were all Catholics who went to the same grade school. But then we discovered rock and roll music, The Beatles, The Stones, and then we discovered hairstyles, and clothing and make-up, that straight people just weren’t into. We just gravitated towards each other because we liked all the same things. It was immediately obvious we were different, but it wasn’t so obvious that we were all gay. But that’s how it turned out.”

“By the time I got to high school, I was like, I’m going to have to marry a girl otherwise people are going to hate me. But things were changing, fast, and by the time I got to college, everything was just unfolding and changing in front of our eyes.”

“Dressing up was a big thing at that time,” said Dick. “We’d see rock and roll stars who wore high heels, wild clothing, glitter painted faces…and we thought, hey, maybe this is something I can get into and meet other people like me.”

Jim “Sully” Sullivan, on the other hand, grew up on Milwaukee’s East Side near Cramer and Newberry and attended Marquette High School. That’s where he met Dick Varga, and eventually, he befriended Chuckie Betz, Gary Pietrzak and John "JP" Pelokonis. The gang would spend their weekends downtown at Marc’s Big Boy and the Loop Café with other queer youth, drag queens, and trans women. Some of these scenesters were affectionately known as “5th Street Pot.”

“The Loop had a great jukebox, greasy cheeseburgers, endless coffee, and big ashtrays,” said Sully. “We’d spend the whole evening there.”

“I knew I liked guys then, but couldn’t express it,” said Sully. “I hitchhiked everywhere hoping to get molested by someone, but it didn’t happen until later. I wasn’t sure what I was, but I finally admitted to myself I was queer. I remember telling Dick, Mark, and Chuckie about it, and they were giggling – because they’d been picking up guys for quite a while.”

The future Bon Bons hung out at East Side drag parties, jazz concerts at the Avant Garde coffeehouse, drinking Harvey Wallbangers at The Rooster…”it was quite a wacky time, and a dangerous one too. If we missed the last 15 bus, we’d get chased by gangs of guys in cars while walking home.”

Sully and Dick moved to Madison for a while, and the others visited regularly for crazy times and colorful characters. They later returned to Milwaukee for art school at UWM, where they joined the gay liberation organization, painted revolutionary messages on campus walls, and protested “bad gays” like The Boys in the Band.

Bobby Lambert

Bobby Lambert

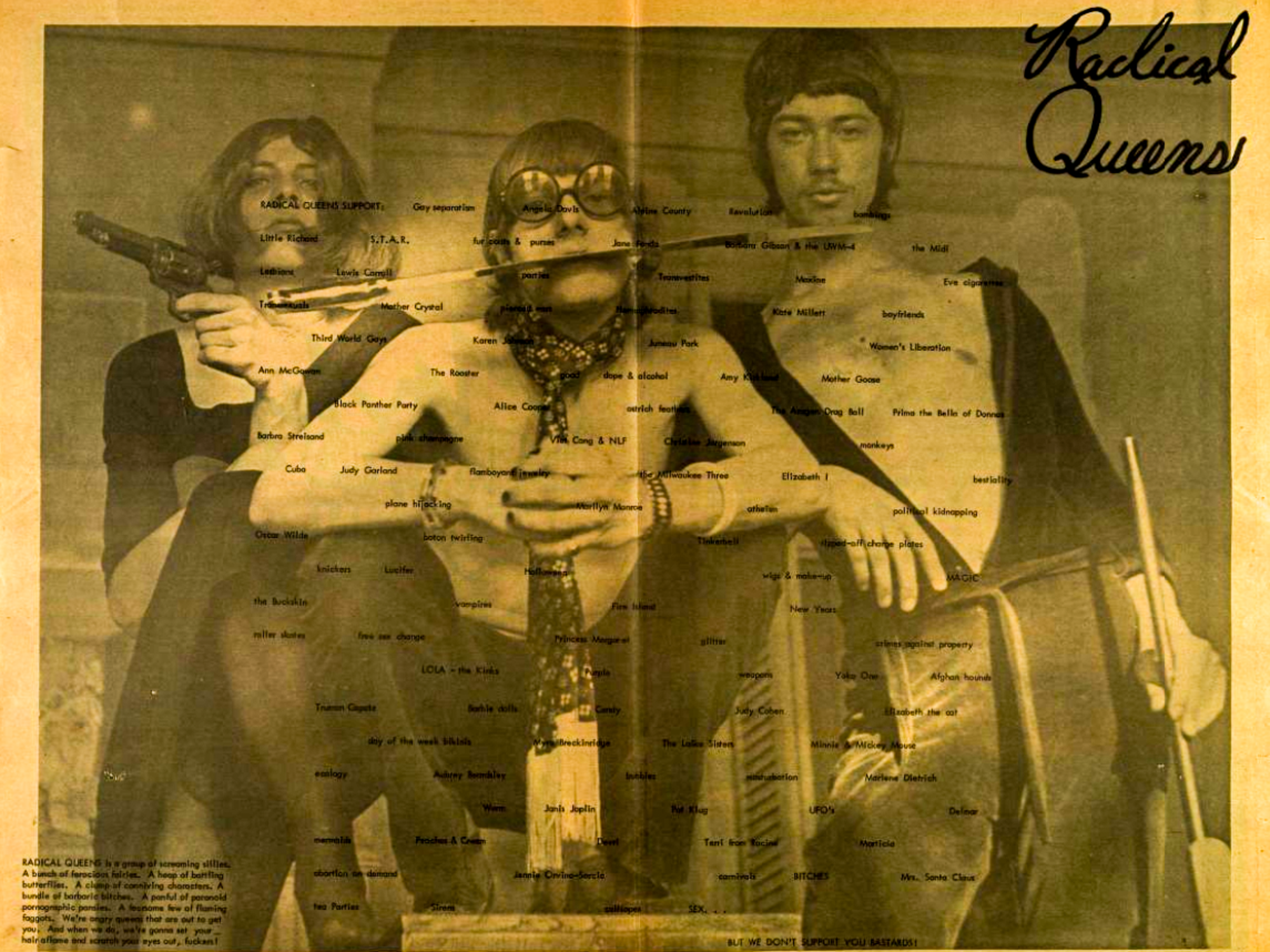

Radical Queens

Radical Queens

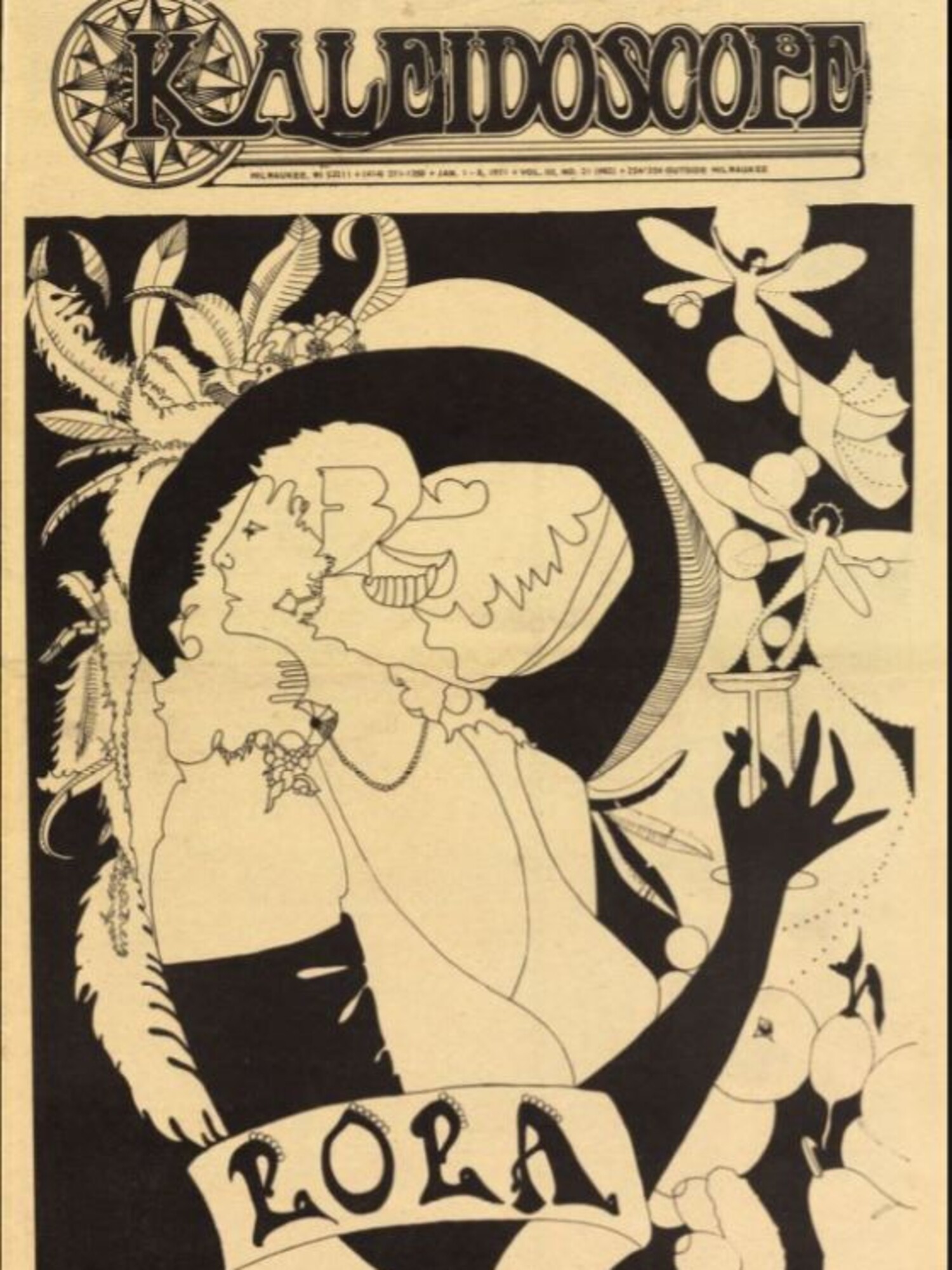

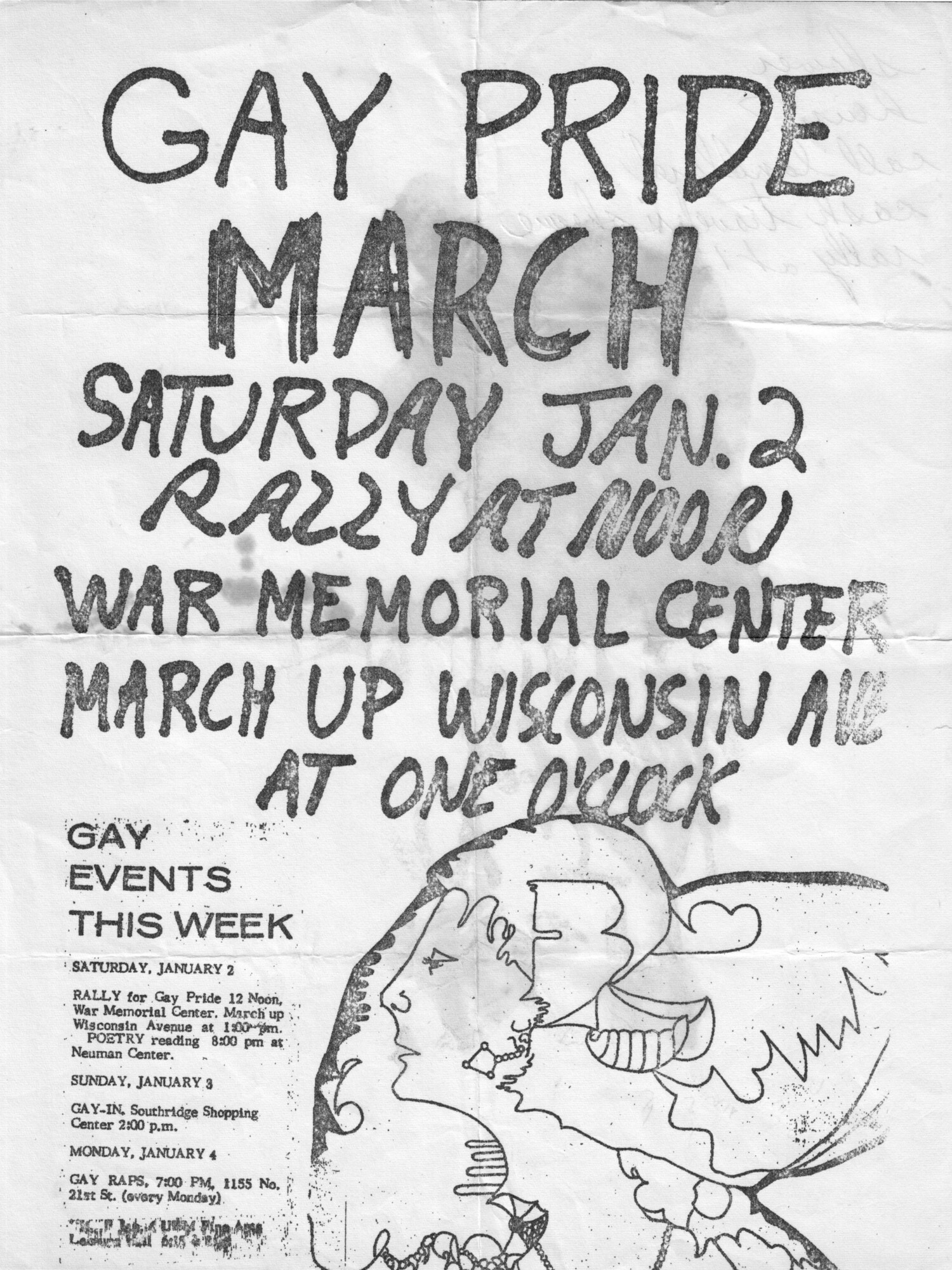

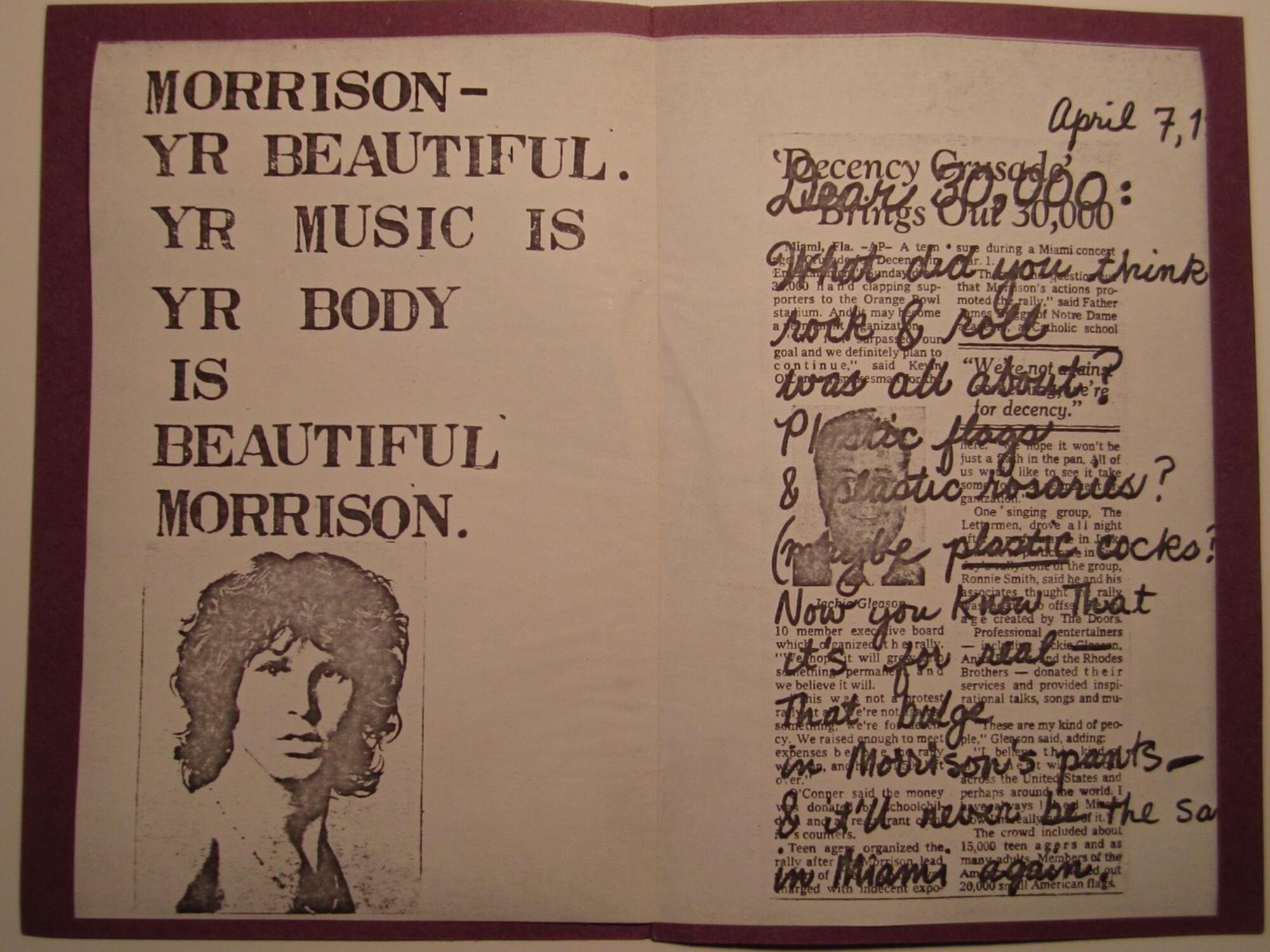

In January 1971, Gay Liberation Front took over Kaleidoscope magazine to celebrate the first-ever Gay Pride Week and March. The centerfold was a double-page fashion blow-up of Chuckie Betz, John "JP" Pelokonis, and Gary Pietrzak as the Radical Queens. This was an incredible demonstration of queer visibility.

The Radical Queens were already known for their subversive antics: hosting a walk across town on stilts, staging a Mad Hatter tea party complete with silver service stolen from a local museum, throwing a mock gay wedding where the attendants were monkeys, scheming to break into an East Side pharmacy but imbibing on the loot and passing out on the floor, taking over city bus lines and department store escalators in full drag.

Like many of the Bon Bons’ grand plans, this show was never actually produced. Instead, the Bon Bons became a synthesis of art, politics, and sex at the crossroads of social revolution.

“The Gay Revolution: Raid, Riot Marked Turning Point for Movement,” by Neil D. Rosenberg, was the first Milwaukee media mention of the group:

“Les Petit Bon-Bons (sic) is one of four gay groups now operating in Milwaukee. According to their anti-manifesto, the goal of this group is the ‘perpetuation of madness; we’re all crazy.’

‘Our lives are our art. Our art is our politics. Our politics is the way we make love. We believe…gay people have a responsibility to sabotage seriousness.

‘We demand not just the end of our oppression as gay people, not just happiness, but ecstasy, which is eternal delight.’

‘Les Petit Bon-Bons (sic) are alive and at play in the Milwaukee area today. We’ll be visiting your neighborhood soon. You can’t miss us.” (Milwaukee Journal, February 29, 1972.)

Self-described as a “group of gay life artists who live and play in and around Milwaukee, Hollywood, and the World,” Les Petites Bon Bons invited America to “imagine a gay universe” with enticing correspondence art. They were so loosely organized that “Bon Bons” became an umbrella open to anyone who subscribed to its ideals. Anyone who wanted to be a “Bon Bon” could take on that name, which only advanced the popularity and impact of the group.

But what were the Bon Bons supposed to be, exactly? Nobody was quite sure, including the Bon Bons. “We are poets, and we are dancers. Les Petites Bon Bons is the name of the play, a group of rock musicians, a gay twirling corps, a traveling circus,” they said. “From the beginning, we didn’t want anyone to be sure of who or what we were,” said Bobby Lambert.

Bobby Lambert moved into the second floor of “The Astor House,” a beautiful – and soon to be infamous home -- on the northwest corner of Astor and Ogden. Dick Varga, Jim Sullivan, and JP rented a space downstairs. Chuckie Betz met Jerry Dreva through Gay Liberation Front.

“I knew who they were, but we weren’t exactly friends yet,” said Bobby. “They were much younger than me, and when you’re young, a few years is a big difference.”

The Bon Bons were shockingly ahead of their time. Not only were they significant influencers of fashion, art, nightlife, and media, they specialized in socially disruptive pranks and hoaxes that shattered the rigid mainstream world. Freedom of expression allowed them to escape from conventional morality.

Throughout their innovative existence, they became famous simply for being famous. Their lasting influence can be seen on the New Romantic scene of the 1980s and the Club Kids scene of the 1990s.

“Somehow, none of this seemed weird to me, even now,” said Dick Varga. “It was just the times we lived in, and the brotherhood we shared between us. We enjoyed a kind of unity that doesn’t exist today.”

“In the course of their work the Bon Bons inspired, befriended, amused, angered or merely confused many of the public figures of their time,” wrote Bobby Lambert. “In the end, there were few who did not know, or think they knew, Les Petites Bon-Bons.”

But Les Petites Bon Bons were far too high-concept for Milwaukee. Jerry and Bobby had traveled Europe, briefly lived in New York, and intersected with cultural icons of their era, including Marsha P. Johnson, Sylvia Rivera, Yoko Ono, John Lennon, Candy Darling, Jackie Curtis, and more. They were fascinated with the Warhol Factory scene, attending parties at Max’s Kansas City and stage shows at La Mama.

Richard Cromelin, a childhood friend of mutual connection Ben O’Loughlin, was now an established rock critic with an impressive personal network. The American media was quickly becoming a “public relations culture that feeds indefinitely on the entertainment industry of Los Angeles.” Regaled by stories of the Bon Bons, Richard insisted they come to Hollywood. Jerry Dreva headed to Los Angeles alone on May 29, 1972, followed by Bobby Lambert in January 1973.

“Even Hollywood would never be the same,” said Bobby Lambert.

Fashion

The Bon Bons were powered by public attention, decades before social influencers, and invested heavily into uniquely curated looks. The Bon Bons look was described as “the future in the past reflected in the moment,” including harlequin mirrored sunglasses, Italian whale-toed platform pins, shoes, scarves, necklaces, bracelets, rings, crocheted belts, and excessive accessories. Some of the members were into scare drag, others fully committed to extreme genderfuckery, and some never did drag in their lives.

It didn’t matter. All were Bon Bons.

“Thrift shop hippie glamour met classic drag on an acid trip and took it from there. It became like childhood dress-up play,” said Bobby Lambert. “Chuckie was a real expert in adornment. I began to sew, but we had lots of time. At this point, we had become unemployable.”

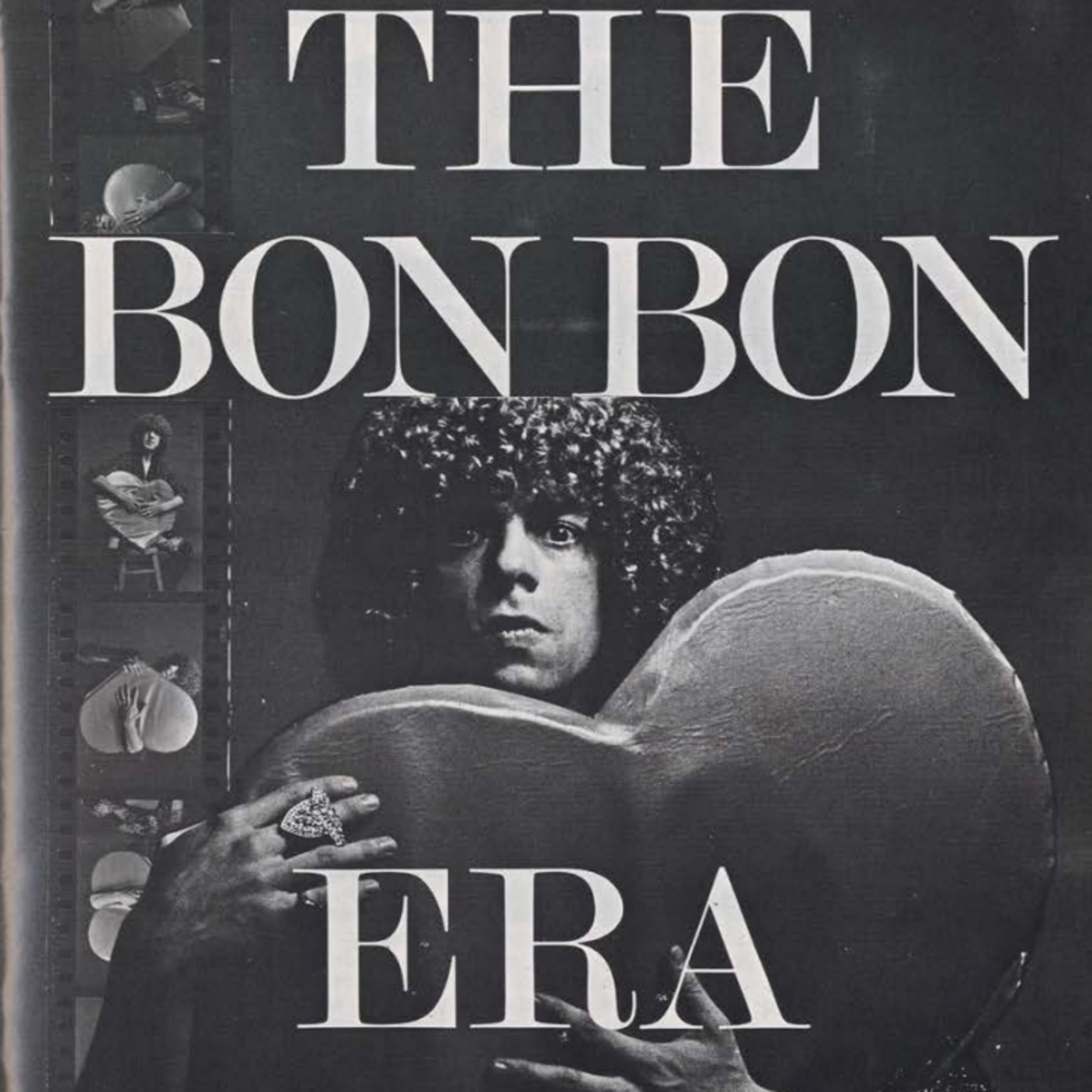

In early 1971, Milwaukee photographer Francis Ford read a Rolling Stone article about The Cockettes and sought drag queens to photograph. Through mutual friends “Silent John” Stegman and "Caesar," Ford eventually connected with the Bon Bons.

"It was so ironic. I wanted drag queens, and they found me drag queens -- in Cudahy," said Francis Ford. "I thought that was crazy. Drag queens in Cudahy?"

"So, I went down to see them. Most of them had asshole fathers who didn't want their kid in drag, and there he was, muttering in the back corner, while I was chatting with their more friendly moms. That's how it all got started."

Soon, they struck a deal: Ford could take all the photos he wanted, if he printed copies they could use to promote their cause.

“I’d spent my life preparing for this opportunity, as if perfecting his call,” said Bobby Lambert,

The Bon Bons photo shoot was a riotous night that ended with a bottle of vodka spilled into an electric typewriter. Legendary photos were born that evening -- and later displayed at a Milwaukee Art Museum juried competition. The Bon Bons had big plans for opening night.

“The museum allowed me two tickets, so I brought my mother and told the Bon Bons to come anyway,” said Ford. “When confronted with half a dozen questions in bizarre costumes, including Chuckie Bon Bon in a diaphanous gown that lit up when plugged in, the matron at the ticket table turned them away. I told her that if she didn’t let them in, I’d take all my work and leave. She backed down.”

“My favorite moment: a guy in a Green Bay packer sweatshirt took one look at Chuckie, and said to my mom, ‘what in the world was that?’ and she deadpan replied, ‘that’s my son.’”

Meanwhile, the Bon Bons installed label cards crediting themselves for light switches, drinking fountains, and other non-art throughout the exhibit. Just for kicks.

The Ford photos became the foundation of a new Bon Bons media blitz that canvassed the region.

"They sent out postcards to all these people, inviting them to events that simply didn't exist, building up a brand for themselves," said Ford. "Their drag was outrageous, outlandish, confrontational... it may not have always been pretty, but it sure was effective."

On May 21, 1972, Jerry Dreva hung 40 Les Petites Bon Bons posters around the St. John’s University campus at midnight. He remembered a freshman asking him, “Hey, where are those guys from?” “Milwaukee,” he answered.

“What do they do?”

“Nothing.”

Little did they know how much “nothing” was about to happen.

Art

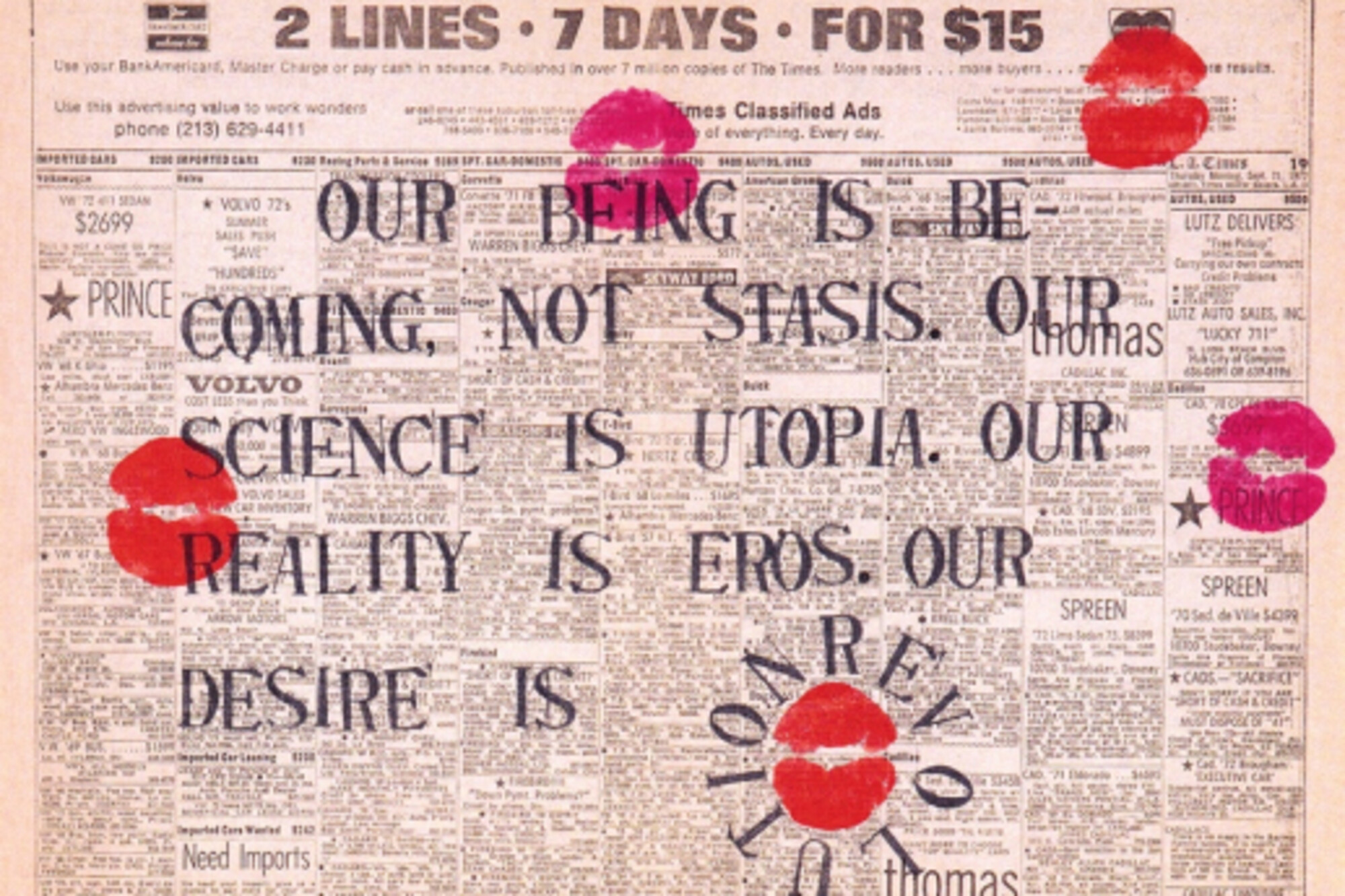

Since 1971, the Bon Bons had been sending hand-crafted, artistic gifts for people they admired, including journalists, artists, musicians, and authors. Their artwork incorporated gay camp, glam rock, and street art to create a unique alternative to the mainstream gay liberation movement. Using photocopied texts and images, they created a compelling new brand of visual counterculture. These mailings, including posters, toys, candy, and glitter, became legendary.

“It was great fun, because we were all pioneering,” said Bobby. “This was all new, not only to us, but to the entire world. It was just outrageous what we could get away with. Everything was so structured, and nobody ever questioned anything. We found that if you moved outside the rigor, you could find all sorts of little wormholes through things.”

“And it was also long before the internet. We used the mail the way people use the internet now, but we had access to everyone, and we could do anything.”

“Mail art was inexpensive, required no infrastructure other than the postal system, and allowed for word-of-mouth advertising…. which gave the feeling an alternative scene was emerging,” said Kristen Olds.

“Addresses were easy to come by,” said Bobby Lambert. “Everyone was in the phone book except the very few who had unlisted numbers. The entire United States Postal Service was at our disposal. Andy Warhol. William Burroughs. Christopher Isherwood. Rona Barrett. And why not? Even when we didn’t get replies, it didn’t diminish the secret thrill that we had reached them.”

Packages went out to Bette Midler, Peter Allen, Marc Bolan. The Kinks. Rod Stewart. David Cassidy. And many, many more.

“Jerry had a lifetime of quotes from people he admired in the books stacked around his room. We stole freely from the best and brightest -- and added our own. They became our platform ‘Bon Bon mots.’ They were typed in tight blocks and scattered around a page like an elementary school project.”

Art critic Jack Burnham wrote back on April 6, 1972, sharing, “All I can say is more power to you and Les Petites Bon Bons, culturally you’re part of the wave of the future, and it you can get it out into the street and make the little people think, you’ll be doing something that museums just can’t do.”

Arthur Bell, who reported on the Stonewall Riots, replied on April 14, 1972: “Should you come east one of these days, do say hello. Meanwhile, blow those bubbles my way. I’ll blow mine back.”

In Los Angeles, the Bon Bons made “packages” (also known as press kits) and sent them to their favorite rock stars’ hotel rooms. They viewed the work as a ritual sacrifice: elaborate pieces designed with wit and beauty; walked a thin line between rumor, hazard, and myth; and manipulated and mutated the media in the process.

“Through Richard's interviews, we knew where our targets would be staying,” said Bobby Lambert. “On some occasions, Les Petites Bon Bons went along; in other cases, we sent packages filled with jewelry, plastic toys, diverted comics, collages, committed texts, and t-shirts with our logo. The New York Dolls, for example, received cut-outs of paper dolls with their heads glued on them, while David Bowie was the recipient of a set of works composed with a quote from Antonin Artaud and a giant photograph sparkling from him.”

Jerry Dreva’s mailings to David Bowie were so influential that they inspired the cover of his single, “Ashes to Ashes.” The first 100,000 copies were covered with stamps, and the word “Bon Bon” appears on one of the stamps.

“We were coloring and defining and era,” said Bobby Lambert, “holding up a mirror to culture and seeing the reflection materialize. We collaged ourselves into the cultural landscape. We weren’t trying to invade the musician market, fuck the stars, or get into the movies. We were starring in our own fantasies, and they were already the best.”

“It was world-changing to find that other people were doing this too. We had no idea that correspondence art was a thing. We just hatched this on our own.”

Music

“It’s 10 p.m.,” TV stations around America asked. “Do you know where your children are?”

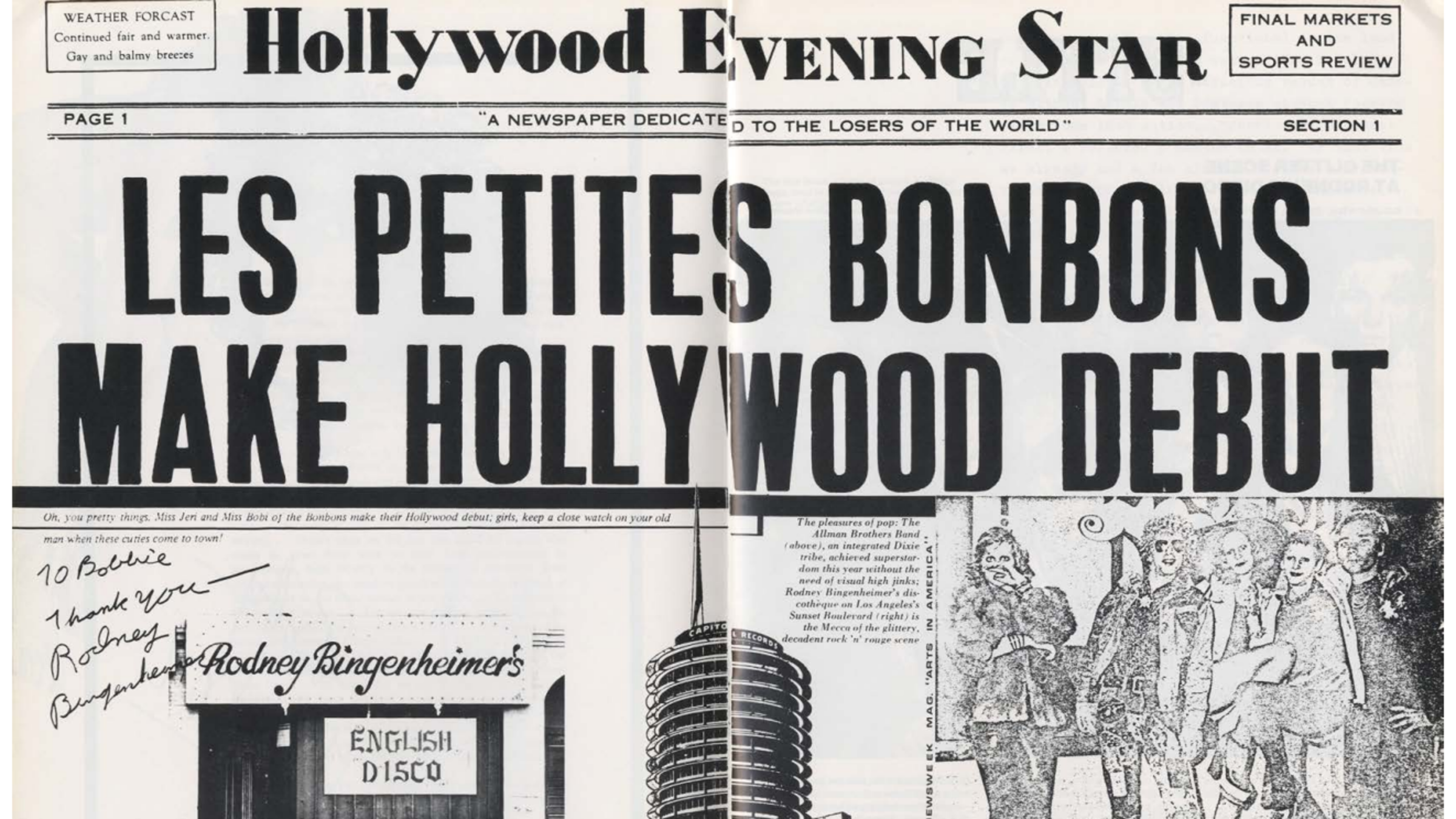

In Los Angeles, they were at Rodney Bingenheimer’s English Disco, which attracted glitter rock groupies aged fifteen and up in scene-defining fashions: skin-tight satin pants, Lurex halters, ten-inch platform heels, and a polysexual/pansexual vibe far ahead of its time. Rodney’s disco was pure gold – and for years, it was rumored he would be franchising them nationwide. He’d convinced RCA Records to sign David Bowie, and now the club was leveraging Bowie’s popularity to attract even more business.

Within four hours of arriving in Los Angeles, David Bowie called Jerry Dreva on October 20, 1972. It was the "ultimate response" to a Bon Bons package ever.

Cromelin’s connections allowed the Bon Bons to meet and interview visiting musicians. Writing for Phonograph & Record Magazine under pen name Lisa Rococo, Cromelin carefully planted Bon Bons stories that triggered a serious fear of missing out for Sunset Strip youth. Everyone wanted to know the latest sensation.

“The Bon Bons had the image, the lifestyle, and the notoriety of rock stars,” wrote music critic Simon Reynolds. “They appeared in the music press of the time, within the magazines Creem, Record World, Rock Scene, Melody Maker, and New Music Express, as well as Newsweek and People.”

“There was so much money in the music business that they could throw it anywhere, at anyone,” said Bobby. “Historically, that was a very narrow window for new musicians to be able to make that much money. Record sales allowed studios and executives to make just about anyone happen. And that’s why we got so much interest. There was always this possibility that we could be turned into money, and some people just kept on trying.”

Phonograph and Record Magazine loved them so much, they got Jerry and Bobby into the studio to record promo spots.

“They were willing to promote us in any way they could, allowing us to find our own form, to see what kind of following we might develop,” said Bobby. “However, we were both hopeless at it, and the attempts were abandoned.”

Les Petite Bon Bons did curate a community of fans, eager to follow the trends set by their idols. They knew that the glam rock scene was defined by its most passionate fans, people like Sable Starr, Lori Lightning, Queenie, and others who had become self-made stars of their own. Bobby Lambert and Sable Starr would later co-star on “The Real Don Steele Show” at the peak of their fame.

"This is Los Angeles," spring 1973.

"This is Los Angeles," spring 1973.

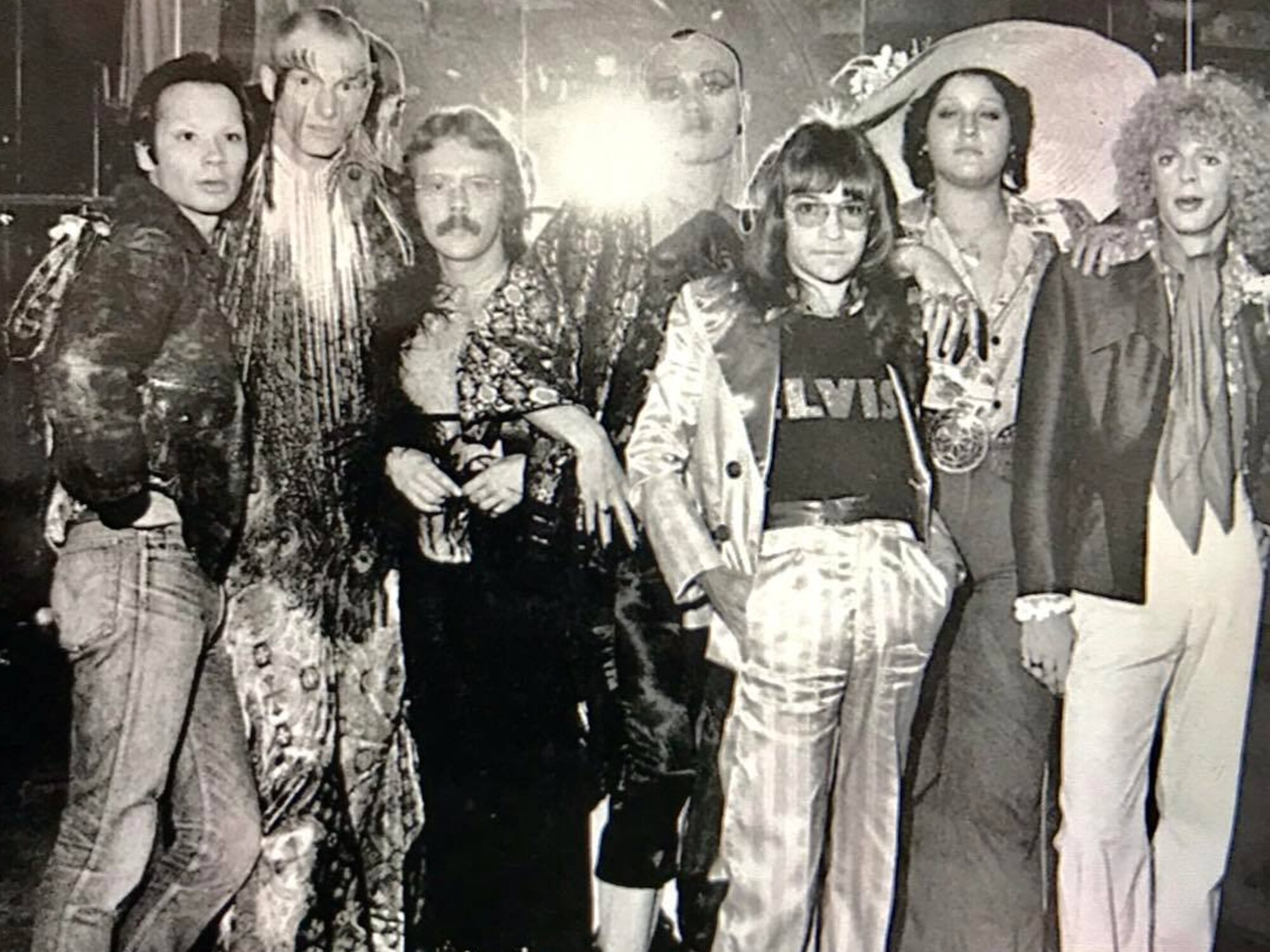

The Bon Bons and Rodney outside the English Disco, 1974.

The Bon Bons and Rodney outside the English Disco, 1974.

Media

“I’m just smack in the middle of the whole rock and roll scene and it’s just maddeningly fantastic,” wrote Jerry Dreva on June 8, 1972. “Everyone just presumes that everyone else here is famous in some way or another. Everyone here is a groupie to someone else. The rock establishment, for all its apparent power and size, is a small little clique. Richard has given me complete entrée into that world. It’s all too crazy for me, I don’t know what I’m doing, and I don’t know how I’ll stand it.”

Dreva, who suffered from bipolar disorder, was alternatively repulsed and seduced by the Hollywood scene. A month later, he wrote:

“I want to be famous; I would be miserable being famous,” said Jerry. “The lights, glitter, and glamour only mask the sores, pimples, and scars. It’s no different than Bucyrus Erie where my father spent his life working. You just die from an overdose or cirrhosis instead of lead poisoning. It’s a grim sort of glamour, Hollywood.”

The Bon Bons were aggressively aspirational, but also extraordinarily expert at self-promotion. They created access, seized opportunity, and built relationships that became gateways into the volatile Los Angeles music scene.

“The glitter rock scene provided them with a place to actualize their ideas about art as a practice of life…alluding to their life as a performance, the Bon Bons declared, ‘we want to be a traveling exhibition,” said art historian Kirsten Olds.

“The door opened, we came in,” said Bobby Lambert. “The only thing you really must do is be there and make yourself indispensable for the camera. This part was so simple. But without Richard, it would not have occurred to us to target this environment, any more than any of the other identifies we assumed. Infiltrating this universe also involved contacting the main actors of the movement being as close as possible to the stars to amplify the simulacrum.”

““I had always told friends in Milwaukee that if you wanted to be famous, all you had to do was look like you were, and it shocked me to find out how true that was, even in Los Angeles.”

On January 2, 1973, zine Gay Sunshine featured a double page center spread of the Bon Bons. Only eight thousand issues were printed, and they are precious mementos to this day.

Within 96 hours of Bobby’s arrival, a photo of the Bon Bons outside Rodney Bingenheimer’s English Disco was printed in a rock magazine, with the caption “This is Los Angeles.” The photo, featuring Jerry and Bobby in psychedelic glitter rock style, caused a worldwide fashion sensation through UPI syndication. They’d arrived at exactly the right moment in history.

Many assumed them to be a high-concept glam rock band, although they had no musical abilities, had never played a concert, and never claimed to be musicians. The assumption served them well in Los Angeles, where they intersected with the heavy hitters of the era, including David Bowie, Iggy Pop, Lou Reed, Sylvester, Mott the Hoople, the New York Dolls, Three Dog Night, Robert Plant, Led Zeppelin, and Elton John. They partied at the Rainbow, the Troubadour.

Bobby’s first Hollywood party, hosted by Leee Childers, welcomed guests of honor Cherry Vanilla, The Stooges, and Iggy Pop to town. Susan Pyle from Interview Magazine introduced herself, saying “I know the Bon Bons – I’ve seen your stuff hanging up at The Factory.” Photographer Sam Emerson booked a studio session with Jerry and Bobby a week later. Later, they attended a pre-opening private screening of Last Tango in Paris with Marlon Brando, Maria Schneider, and David Bowie.

“The Bon Bons: art for appearance’s sake. They follow the lead of the Marx Brothers and the GTOs: invade a gathering in numbers, and never allow anything you do to make sense. Their mailings of inspired garbage should be saved for the time capsule which documents the decay of 20th century culture,” wrote David Marsh in “Making it in Hollywood: The Heavy Half Hundred,” a Hollywood Special Report that also included Iggy Pop, John Cale, Frank Zappa, Doug Weston, Brian Wilson, David Geffen, Phil Spector, Terry Melcher, Neil Bogart, Dr. Demento and other big names.

In October 1972, the Bon Bons were delighted to see Michael Itkin wearing one of their custom T-shirts in The Advocate, and even more thrilled to read this mention in a T. Rex concert review in Melody Maker:

“Les Petites Bon Bons were there, of course, serving as the focus of the biggest flock of stare-getters the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium has held in some time. I’d pay money for any concert if I knew that Ruby, Wendy, the Bon Bons, Patti and all the rest of them would be there.”

“Who are Les Petites Bon Bons and why are they sending Clean Prexy Earl McGrath rhinestone studded postcards?” wrote John Gibson in Record World magazine in December 1972.

John Francis Hunter, author of Gay Insider (1971,) a travel guide to New York City, received fan mail from the Bon Bons that he included in his next book, Gay Insider USA (1972.)

Hunter wrote:

…one of the most spirit-lifting pieces of ’72 came from a Cudahy group known as Les Petites Bon Bons… the envelope was pasted up with a N.Y. skyline postcard and cherry and reindeer stickers. Zip code was 5311OH!

Then, inside, the photo for a cluster of gorgeous gender defiant freaks made my heart leap up and warmed The Cockettes of my heart.

Les Petites Bon Bons asked for nothing, gave no prosaic explanation of who they are, just three lovely pages of super-identifying one-liners, quotes, lyrics, and well, let me share a few:

“We have no art. We have only life which is one and gay. LPB erase the straight line between life and art and give you ecstasy. LPB are both carrion crow and the rising phoenix, soon to become the bird of paradise. We don’t believe in positions. Gay people have a responsibility to sabotage seriousness (Charles Ludlam.) Meaning is not in things but in between (Norman Brown.) There’s room on the Bon Bon cloud for anyone who wants to move from work to play, from productiveness to receptiveness, from security to the absence of repression, from delayed satisfaction to immediate gratification, from the fetishism of commodities to the erotic science of use values. To dance is to live (Isadora Duncan.) We aim to radiate power, not possess it (Henry Miller.) Everything we do is music (John Cage.) By having fun, we are fighting the straight man’s inebriation with death. Our lives are our art. Our art is our politics. Our politics is the way we make love. We are poets and we are dancers. LPB is the name of the play, a group of rock musicians, a gay twirling corps, a traveling circus. We are the $64,000 question. Everything they say we were, we are – and lots more they haven’t even dreamed of yet.”

My dears, I have you on my wall, I hope you don’t mind. You have immortalized yourselves. There was a star danced, and under that, you were born.

Hunter was facing a court case against his publishers, who had butchered his original manuscript. In November 1972, he wrote, “Dear Bon Bons, wherever you are, I imagine NYC is quite ready for a gallery showing of Gay Bon Bons – but where, how? I know why: the world would be so lucky.”

Nick Kent, music critic for NME, mentioned the Bon Bons in his glowing review of David Bowie’s March 12, 1973, show at the Palladium:

All the way down the Hollywood Hills, along the Sunset and Hollywood Boulevards, a blend of paranoia and general unease reigns supreme.

Whatever else though, Bowie has bowled the folks over here on the West Coast too, which is logical because California is obsessed with the superficial. Bowie serves up just that, with every embellishment catered for.

I witnessed our hero’s Los Angeles show at the Palladium, a theatre crammed full of poseurs, more concerned with checking out what everyone else was wearing than being part of the rock ‘n’ roll experience. Bowie’s friend, the notorious Iggy Pop, now resident in Los Angeles and looking especially bizarre in bleached Beach Boy blond hair and bronze suntan, strutted around the hall with Coral, his 16-year-old girl friend, a permanent sneer on his already demented features. He was trying hard to stay above becoming yet another fixture of the Los Angeles Satyricon.

Aficionados of the aforementioned are on the whole a particularly bogus crew, boasting such as The Petit Bon-Bons, two ambiguous buffoons known as Geri and Bobbi whose specialty is posing in popstar dressing rooms with a whip and sending ornate greeting cards to their current fave-raves.

Then there are all those sweet young girls, average age 15 and all refugees from “Star” magazine and Rodney Bingenheimer’s English Discotheque, who pout at each other, look like rejects from the New York Dolls and forever boast of their conquests with rock idols. The anguish their mothers must go through… well it doesn’t bear thinking about, my dear. And the beat goes on.

And on, and on, it seems, for here in Los Angeles the tedium is the message. One quietly wonders just how long people will go on kidding themselves into placing boredom in the category of ‘chic.’

In April 1973, they were featured in Phonograph and Record Magazine with the caption, “would you put us in your magazine if we wore dresses?” The article challenged readers to identify the stars for a free subscription. The contest attracted hundreds of guesses, including Bette Davis, The Osmonds, Alice Cooper, The Beach Boys, and The Rolling Stones. Only thirty-nine correctly identified Les Petites Bon Bons.

The winning entry wrote:

“The Les Petites Bon Bons are a group of gay life artists who live and play in and around Milwaukee and Hollywood. The future sees them in New York, but then, the future sees them in many, many places. What counts is where they are not. So far there are seven Bon Bons, all of which are gay males. They are loving, imaginative, carefree, and childlike. The Bon Bons aim to be a walking exhibition. Out of the closet galleries and into the streets. If you’re an interesting person (to the Bon Bons,) you can bet your snakeskin boots you’ll be receiving a package of assorted goodies from them. What else can I say about the Bon Bons except, boy they’re terrific.” – signed with loving kisses, Ms. Patti Clemente, New Orleans, LA.

But nobody was better at promoting the Bon Bons than the Bon Bons themselves, who peppered mailings with random, vague promises:

“Soon to be featured in a major motion picture, Les Bon Bons may be coming to your town soon!”

“Win A Dream Date with a Bon Bons contest”

“The Grand Tore of 1974: Hollywood Bon Bons on the Streets of Nude York May 25-31”

“The Bon Bons were artists in residence in the glitter scene, court jesters for rock and roll royalty, interpreters of style for the mass media,” said Bobby. “To hundreds of thousands who saw our photos in Newsweek, People and other publications, the Bon Bons became the personification of the glitter era and later the proto punk era.”

Bon Bons packages were regularly seen on the walls of Andy Warhol's Factory.

Bon Bons packages were regularly seen on the walls of Andy Warhol's Factory.

The Bon Bons "invaded" a contest winner's meeting with David Bowie at Los Angeles Union Station.

The Bon Bons "invaded" a contest winner's meeting with David Bowie at Los Angeles Union Station.

Social disruption

The Bon Bons were mercurial tricksters, relentlessly pranking a world of senseless conformity and soulless morality, and their hoaxes only got more extreme.

- Penning letters to architect Buckminster Fuller and Vice President Hubert Humphrey, Jerry presented himself as a political hazard to be handled or as a dead man to be memorialized. Both responded, as a matter of protocol, with well wishes to his deliberate pranks.

- They forged press releases about a fictional baton twirling group organized by Eva Lubin (Chuckie Betz’s drag name) as a wholesome youth activity in Cudahy, Wisconsin. These releases were mailed to marching band newsletters, who profiled the group, and the Bon Bons were put on subscriber lists for national and regional competitions. (Some of which they entered.)

- In April 1973, Jerry sent a letter to the Los Angeles Postmaster honoring Postal Week with the statement, “(we) wish to extend our congratulations and thanks to the postal workers of the entire world for providing us with a portable gallery for our traveling art show this last year. All art is collaboration, and without your assistance, the show cannot go on. We are grateful for the part the postal workers have played in creating our correspondence art game and in recreating a Bon Bon world.”

- During a road trip to Milwaukee in July 1973, Bobby, and Jerry vandalized gas station bathrooms along the way with spray-painted hearts and urinal glitter. They later received a repainting bill for $25 from a Chevron in Wells, Nevada.

- Eventually, they set out to host a competition of their own, which invited hundreds of marching bands from around the nation. The Presidents All-American Festival of Champions, to be held May 15-18, 1974, would include a U.S. Presidential Cup presented by President Richard Nixon. After significant national media coverage, the hoax was discovered. Multiple businesses, named as sponsors of the event, had in fact no involvement at all. The LA Times claimed to be pursuing fraud charges, but no one was ever punished for the prank

“We were testing those kinds of limits, and more and more you just do it, and see what happens with a straight face,” said Bobby. “In those days, they answered us. They think they’re answering their mail and they don’t realize it’s from a bunch of lunatics.”

Meanwhile, the Bon Bons found the “mainstream” gay liberation movement impossibly boring.

“Gay People's Union was more interested in assimilation,” said Bobby. “We felt that GPU was begging for acceptance without challenging the causes of the oppression. The Gay Liberation march was the most confrontational thing they ever did. And that was it. Then they went right back to begging to be accepted. It was a real turn-off.”

Jerry Dreva attempted to connect with the LA gay liberation movement, including the Christopher Street Parade of June 1972, the Griffith Park Gay-Ins, and a November 1972 candlelight vigil against police harassment. Despite meeting organizers like Troy Perry and Morris Kight, he found the scene “retarded” and quickly avoided the scene.

“There are dumb politics among gay people here…very anti-women and anti-fem. The local heavies are very unheavy, very GPU-type politicos, not a real radical in sight,” wrote Jerry.

The time is now

The golden age of Jerri and Boby Bon Bon soon reached fantastical heights.

“Our proudest moments were those filled with pure, decadent fandom," said Bobby. "We attended Elton John's “Yellow Brick Road” Party at the Roxy after his show at the Hollywood Bowl. The guest list included Peggy Lee, Carly Simon, James Taylor, Linda Lovelace…. and somehow, we spent the entire night with Paul Lynde.”

“Another time, a record company hired us to throw a party for Iggy Pop and two hundred of his closest friends. This was my first attempt at event planning. Getting all those people together – Divine, the Loud family, etc. – that was a lot of work. The president of the record company flew in from New York to see this for himself. That was a big triumph for us.”

In August 1973, four more Bon Bons joined Jerry and Bobby in Los Angeles. Their journey was described as “wind-borne lace curtains trailing behind an aging El Camino, wearing satin scarves that would have put Priscilla, that other Queen of the Desert, to shame.” By that time, the Astor House was just a memory – reduced to rubble by developers of the Park East Freeway. The corner would remain vacant for over 20 years after the freeway was cancelled.

The new Bon Bons just in time to see the New York Dolls at the Whiskey A-Go-Go. They couldn’t possibly all live with Bobby and Jerry, so they settled into a hillside pagoda in Highland Park owned by an old queen. They’d found the home through Morris Kight and the LA Community Center, but nobody mentioned that actual monkeys roamed the grounds. Despite aspirational meetings with Hollywood connections, nothing substantial ever materialized for the newcomer Bon Bons.

In some ways, their long-awaited arrival was too little, too late. While Jerry and Bobby enjoyed their company and collaboration, they now felt expected to carry an ever-growing collective.

“Fame was not something we could easily provide for others,” said Bobby. “It was easy for one to tag along to an interview or get into a show or party, more difficult for two, and impossible for six.”

There were also concerns about some the characters hanging on to the Bon Bons name. They adored their old friends from Wisconsin. Some of the others who showed up with them? Not so much.

“I felt some were just there to cash in on some imagined bonanza of fame and fortune we’d supposedly prepared for them,” said Bobby. “I felt all our hard work would be sabotaged by people with no understanding of what we’d accomplished. We were both beginning to feel we were fast coming to an end of our interest in this phase of our work. We’d created an identity. As soon as people thought they knew us, we wanted nothing more than to destroy that notion. Our core philosophy had always been fluid identity.”

“We had become static, and it had to change.”

Yesterday’s Bon Bons

In October 1973, Bobby wrote to a friend in Wisconsin.

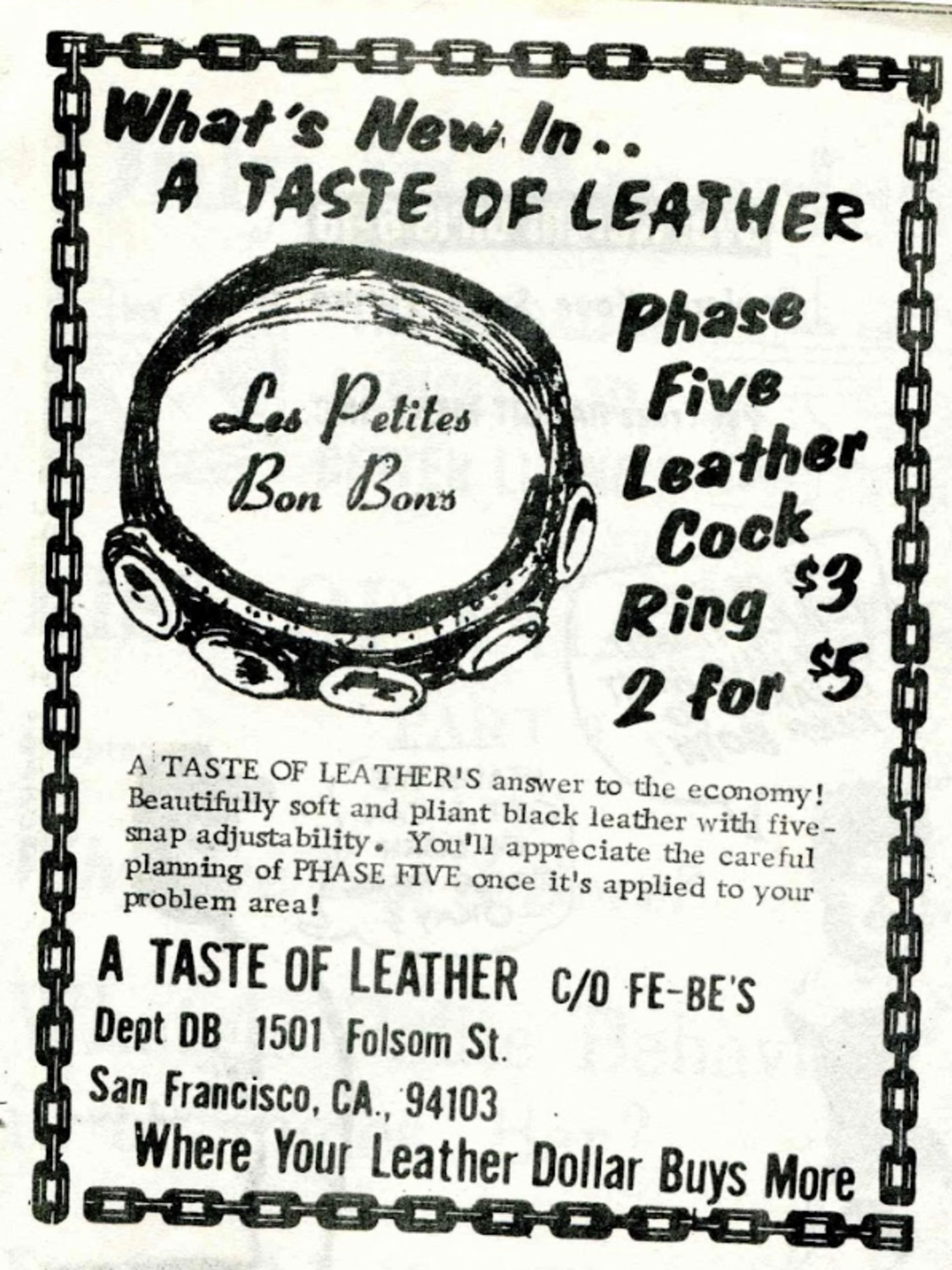

“Strange things have been happening in my life and my head since I’ve been back in California. I have become totally disinterested in the Bon Bons. To me, the era is completely over, dead of natural causes, and there is nothing that restores its inspirational effect on my creativity. I wear nothing but butch Levi and leather drag now…. lots of weightlifting too. Went to my first leather bar and there were all the numbers I’d been looking for, for years.”

After attending the debut of American Graffiti with star Mackenzie Phillips, the Bon Bons wrote “the premiere was a fitting farewell to the glory that was Bon Bons. The next morning, they woke up on their way home, young boys with quite an adventure behind them.” (Log Book, the Grand Tore of 73.)

American Graffiti premiere was considered a “fitting farewell to the glory that was Bon Bons. The next morning, they woke up on their way home, young boys with quite an adventure behind them.” – Log Book, the Grand Tore of 73.

By the time the November Interview magazine featured Rodney’s English Disco, the interview felt like ancient history.

Even Bowie was changing. Once an outspoken glam rock champion for bisexuality and gender fluidity, he was now a thin young man in a suit. His transgressive image worked in the United Kingdom and Europe, but it wasn’t selling in the United States. Bowie later said that admitting to being bisexual was the biggest mistake of his life, and he spent the rest of his career distancing himself from that statement, and by extension, the Bon Bons.

“Bowie was a business, and he was out on the edge,” said Bobby. “They’d spent a fortune on his shows, but he wasn’t yet a money maker. So, they had to do everything they could to assure that he was going to be huge. He had to pay attention to the Bon Bons, as part of his business, as part of his job. He may have liked our work, but the reason he called Rodney, and got our phone number, is that he was taking care of business. I can’t say I blame him. His goal was to be a successful musician, not a political martyr. He'd already been sold. The bill came due. He had to pay it.”

And some of the Bon Bons’ choices were catching up with them.

“There was this whole complicated scheme with check kiting and credit cards,” said Bobby, “and it followed them all the way to Los Angeles. And then, there was the costume shop heist. They’d rented a bunch of theatrical costumes, loaded up the vintage El Camino, and took off to California with them. And then, someone was even accused of kidnapping. The Bon Bons went to a high school basketball game and one of their acquaintances seduced a player right off the playing field. When they arrived in Los Angeles, they’d brought this guy with them. Eventually, the FBI came looking for him.”

Even Jerry was arrested for fraud for one of his hoaxes, but the charges didn’t stick, as “defrauding” people of the truth with no financial gain wasn’t exactly a crime.

In late 1973, they were interviewed by Count Fanzini on a sunny smog-free day.

Les Petites Bon Bons, one of the totally unique anti-sensations of this decade, have been swaggering and dancing their way across that mad canvas we call the seventies. Playing the part of artists, or practicing non-artists, philosophers, pranksters, paupers, and kings, they see their indulgent negativism as “romance.”

“Being a real star is really chance, just happening to be where you are,” said Bobby. “That’s what we saw, sort of the other side of it. It’s public relations. Having an enormous, enormous amount of confidence in yourself and simply putting yourself out there. Somehow people have just liked us – many people, for no reason at all, have just liked us.”

“People will write captions under our photos and say we’re the latest drag rock sensation in LA, when we’ve never given anyone any reason to suspect we are a band,” said Jerry.

“Chuckie and all these other people in Milwaukee were really into making their own fashions, fantastic costumes, and dressing up and going out. DRAG. Getting arrested by the police for impersonating women. Getting beaten up by the boys on the block. Even being a test case for an attorney. I had never been doing that. We felt freedom here – to put on make-up – shave our eyebrows – and historically, it was just the beginning of glitter rock.”

“The Bon Bons are not specific. They’re never specified on the guest list because they never know who’s going to show up under that name. Bon Bons is the magic name here. Sometimes we’ll show up at parties and someone has already gotten in under that name and we can’t! We like that. We’re discovering what it is we are and what other people think we are. Very often we’re outraged when we find out what they think. We hear that we’re so decadent—I’m not decadent, or a junkie, or jetting around the world. It’s total media fabrication.”

The Bon Bons think their next period will be “post-cultural.”

“Are we saving the world? We’re saving ourselves; we’re Romantic and everyone is an artist. We feel mystical about our futures; we’re confident—yet we’re here on borrowed time. We’re totally marginal—the ultimate ‘Borderline Case’—not serving any purpose at all in terms of an established Reality Principle. We want to sabotage the Culture—pull it down with us. The culture is going. We’re just reflecting its fall.”

“We’ve always been considered criminals anyhow.”

“We’re always ready for a change. We hate anyone to presume we’re that image—no expectations are needed. To expect us to be in the glitter, was a challenge to change. I was sure I could never grow a mustache or a beard and suddenly that conception disappeared. But we can’t go to The Outcast in glitter.”

“We started using Yesterday’s Bon Bons,” Bobby said. “The whole scene was punk by then. Within two weeks, I completely changed, and you can see it in the photos looking very, very different. I cut off all my hair, changed my clothes, and started going to leather bars. And that was two weeks after my hair was still big, wild, and bleach blonde.”

“People thought they knew who we were, and we had to change that, because we never wanted anyone to be right about what they thought we were.”

“It was a great time, but it was over,” reflected Jerry in 1980. “Great eras can come and go in five years.”

From glitter rock to hardcore leather, 1974

From glitter rock to hardcore leather, 1974

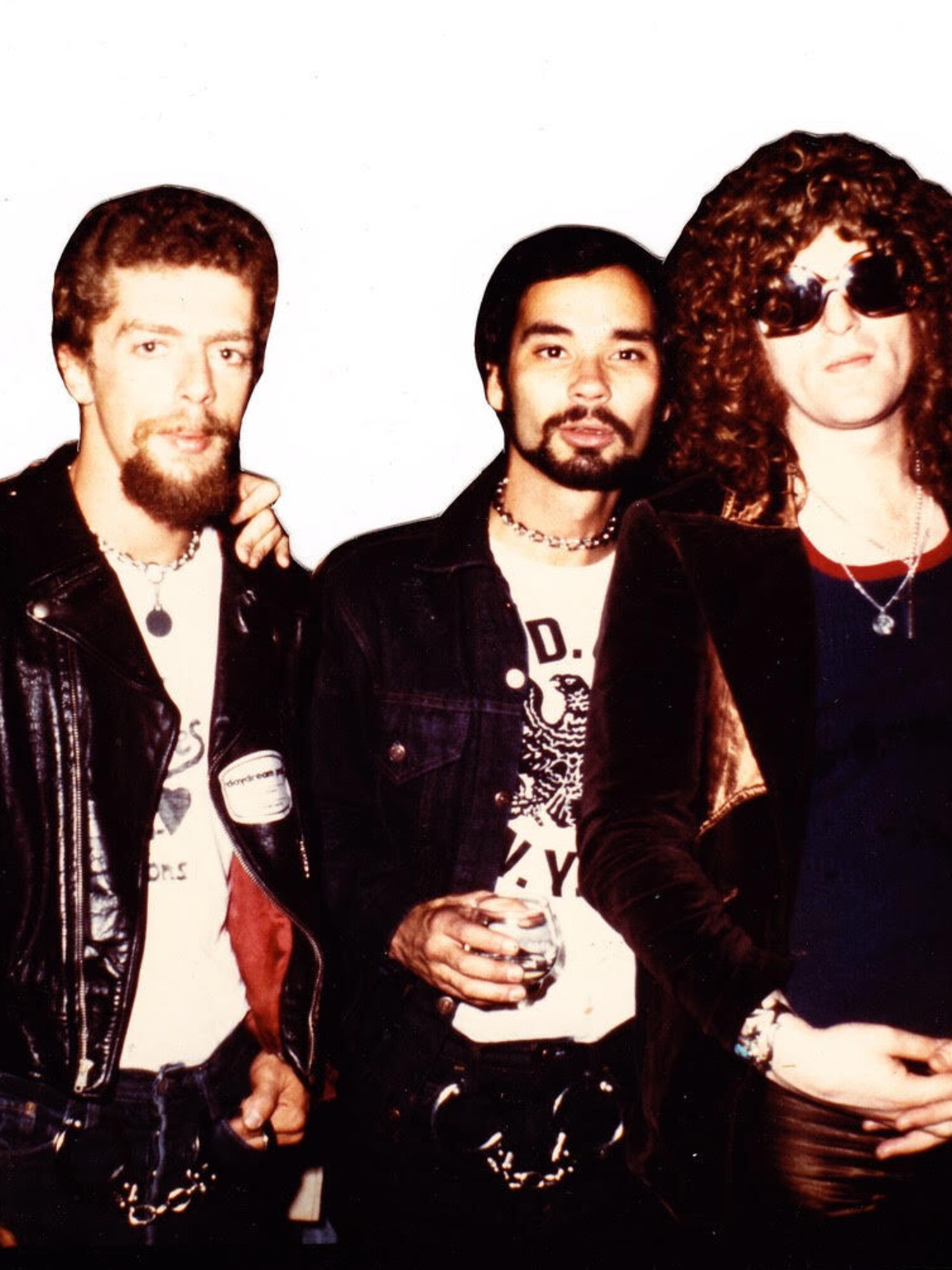

Bobby Lambert, Jerry Dreva and friend, post Bon Bons

Bobby Lambert, Jerry Dreva and friend, post Bon Bons

Where are they now?

With the Bon Bons era over, most of the crew eventually relocated to San Francisco, including Chuckie Betz, Jim Sullivan, Dick Varga, and Bobby Lambert.

Gary Pietrzak died in a house fire in 1996. The whereabouts of Mark Slizewski are unknown.

Jim Sullivan and Michael, his husband of 47 years, still live in San Francisco.

Dick Varga relocated to Palm Springs.

Jerry Dreva returned to South Milwaukee in the 1970s, returned to Los Angeles in the 1980s, spent time in Central and South America, and eventually came home to care for his ailing mother in the 1990s. He died at age 52 in 1997.

After five years in San Francisco, Chuckie Betz moved to St. Louis in 1980 and later returned to South Milwaukee. He lived there until his death on September 12, 2023.

Bobby Lambert lived in California for 50 years before returning to Wisconsin.

Bon Bons artwork has been featured in multiple exhibits over the years, including:

- Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano LA (2017-2022)

- Copy Machine Manifestos: Artists Who Make Zines, Brooklyn Museum (2023-2024)

- Extended Sensibilities: Homosexual Presence in Contemporary Art, New Museum (1982)

A new exhibit will open in Los Angeles in late 2024.

“We were really, very conscious about what we were doing, and we were thoroughly enjoying the fact that feedback was so positive,” said Bobby. “It propelled us forward and we kept moving. We wrote things for the future. Jerry would always write, ‘for future art historians.’ Now, our things are in museums, and it’s so funny, because we half-expected this might happen. We just didn’t think it would take 50 years.”

Looking back across the decades, what would the surviving Bon Bons want to be remembered for?

“Overall, for creating access,” said Bobby Lambert. “For the average person, there was no access to media, nor any expectation of ever earning access.”

“We created access to self-representation, to self-mythologizing, to creating a sense of self. You’re not one person, you can be anything, you can be a dozen different people, you can change, you can adapt, you can explore different personalities and images endlessly. And people still don’t get that. It’s like the elephant that has been chained so long, that once the chain is gone, he doesn’t know he is free.”

“What we did was more interesting than today’s reality shows, because we were aware of the artificiality of what we were doing,” said Bobby. “We were playing it; we didn’t take it seriously.”

“I think we still stand out – and I don’t think anyone has ever approached what we achieved.”

recent blog posts

March 01, 2026 | Michail Takach

March 01, 2026 | Michail Takach

Randy Reddemann: building connections beyond the bars since 1976

February 28, 2026 | Bjorn Olaf Nasett

The concept for this web site was envisioned by Don Schwamb in 2003, and over the next 15 years, he was the sole researcher, programmer and primary contributor, bearing all costs for hosting the web site personally.