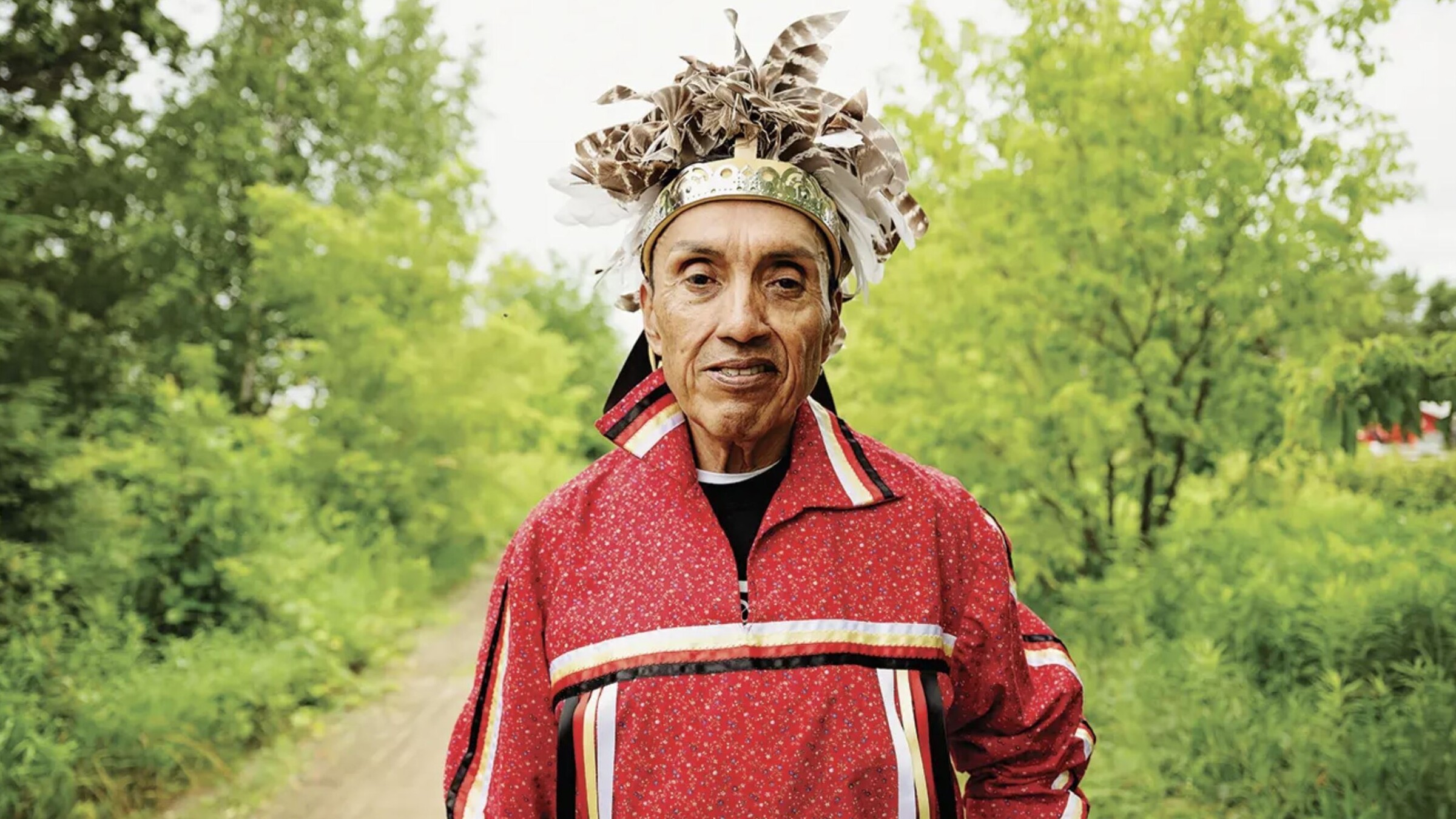

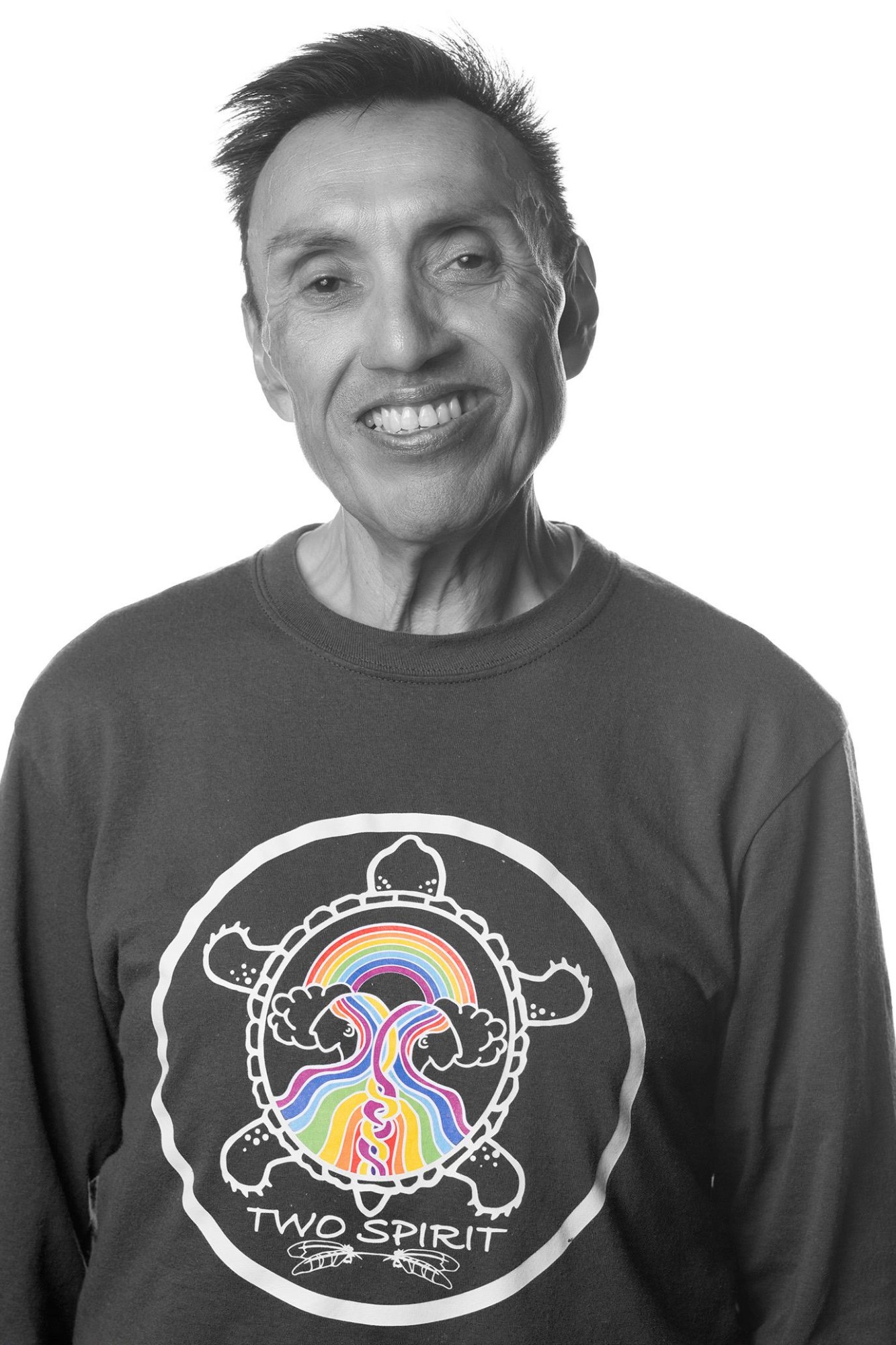

Joseph Ray Torres: reclaiming our culture

Joseph Ray Torres feels the greatest joy when someone asks him to present on the important-yet-hidden history of two-spirit people.

And it’s more than just a presentation to him, it’s an identity—one that gave him a sense of belonging that was missing for so long.

Joe was born April 16, 1965, the 11th of 13 children to two loving parents. His parents met one summer when his dad was in Oneida, Wisconsin, working landscaping jobs. His dad was part Mexican, part Pueblo. His mom was Oneida and spotted him when she was a teenager and brought him lunch every day. Eventually they married when she was 16.

Joe’s parents both thought they should spare their children the experiences they had growing up. They wanted their kids to assimilate and only speak English. Joe was always frustrated that the chance to learn the language of his parents was stolen from him due to the actions of others.

Joe’s father spoke fluent Spanish, but due to experiencing racism, he decided he would not teach his children Spanish. His mother was fluent in the Oneida language, but spent years in a mission school that made her deny her native heritage and afraid to teach the language to her children. Joe begged her to teach him, but she only shared a few phrases.

Joe was in his 50s before he began to learn the Oneida language at UW-Green Bay.

At one such school, Joe’s mother internalized the western narrative that Natives were savages. They were warned to unlearn what Native teachings they were taught and told to not pass on their ways to their children as it would only bring harm.

Joe’s grandmother eventually pulled her daughter from the mission school in 6th grade, but the damage was done.

Joe said that these experiences had a deep impact on not only his mother, but her family, too. He observed that she was “whitewashed in school.”

"Not Native enough"

Growing up was not easy for Joe or his siblings. They did not have a lot of money, and there was a lot of racism directed at him and his siblings from other Oneida due to their mixed background. The Torres kids were made to feel like they were not “Native enough.” The group of 13 siblings were tight knit because of this.

Joe recalls that white kids were always nicer to them than Native kids when he was younger.

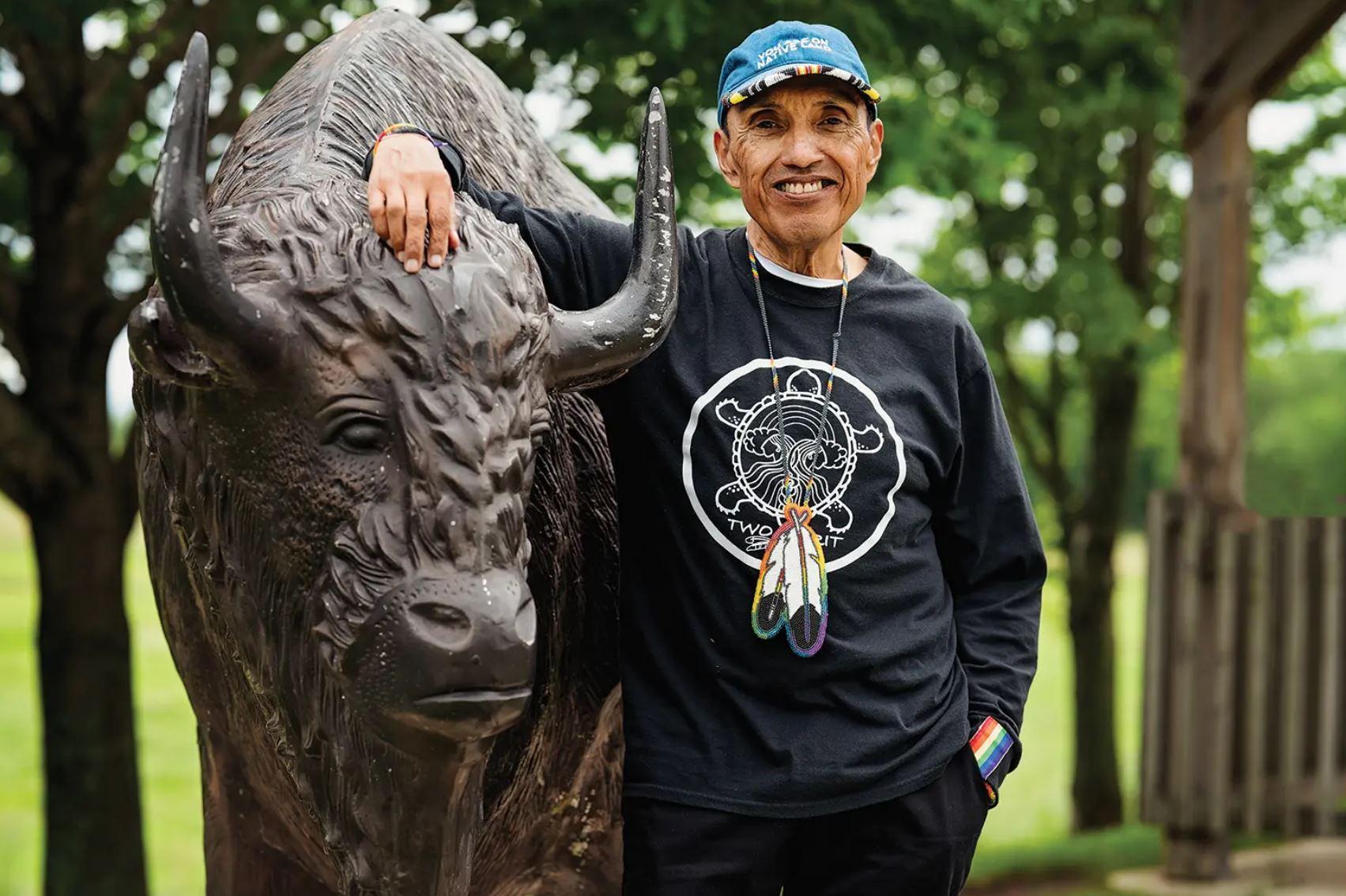

When Joe was in fifth grade, he started growing his hair out long; it was something he was proud of. In middle school, he really committed to it. When Joe reached high school, his hair was down to his lower back. He wore it down a lot, but sometimes it was in a ponytail.

Joe recalled getting harassed in high school by white male students for wearing his hair long. He remembers male classmates yelling “fucking woman” when they passed him in the hallways. Joe was proud of his hair and was not about to put up with nonsense from ignorant people.

Joe knew that the other Oneida students that saw him growing out his hair were inspired by him. Many asked their parents if they could grow out their hair, too, and were not allowed to do so.

Joe as a child

Joe as a child

Joe as a teenager

Joe as a teenager

Not fitting in

Joe was always interested in learning about his Oneida roots. He remembers trying to find books on his people, and he could only find books on the Plains Indians, the Lakota and Cheyenne tribes.

Joe found his heroes in Native history—people like the Nez Perce and Chief Joseph. Joe loved learning about the great warrior, Crazy Horse. His story resonated with young Joe because he did not look like the others, and he did not fit in with his own people. He was of shorter stature and was known to be a great horseman. He was never a chief but fought for his people until the end.

Joe said, “Right around middle school, I knew I was different. I knew I was attracted to men, and my feelings were really strong. I had a close friend who was also Oneida that was one year younger, and I always wanted to tell him that I liked him as more than just friends. I fought it, as I was raised Episcopalian, and I was taught it was a sin. Every night I prayed for these feelings to go away.”

The parents of Joe’s classmates viewed him as a troublemaker and told their children that they could not hang out with him. They thought Joe was a bad influence because he had a reputation for sticking up for himself and others.

Joe had no problem “telling off a teacher” if he felt they were in the wrong. He never fought anyone physically, but he did use his words as a shield. Joe became a frequent visitor in the principal’s office.

Some of the Oneida friends that Joe had were sent off to boarding schools by their parents such as the Flandreau Indian School in South Dakota or the Intermountain school in Utah. The kids who were sent away were ones who Joe used to get into trouble with and sometimes skipped school with. Joe made friends with some other Oneida kids who were good students and did not skip school, and he eventually stopped skipping school. Joe’s teachers and principal noticed the positive change in him and commended him on the improvement. Because many of the Oneida kids were not able to hang out with him, Joe became really good friends with the white kids in his class. This is how things were for him until high school.

In sixth grade, a white teacher read a book about Chief Joseph, and she said it reminded her of him. The teacher took to calling Joe “Chief Joseph” when she addressed him. Joe hated that, as it felt like she was tokenizing and mocking him because he happened to be Native and his name was Joseph.

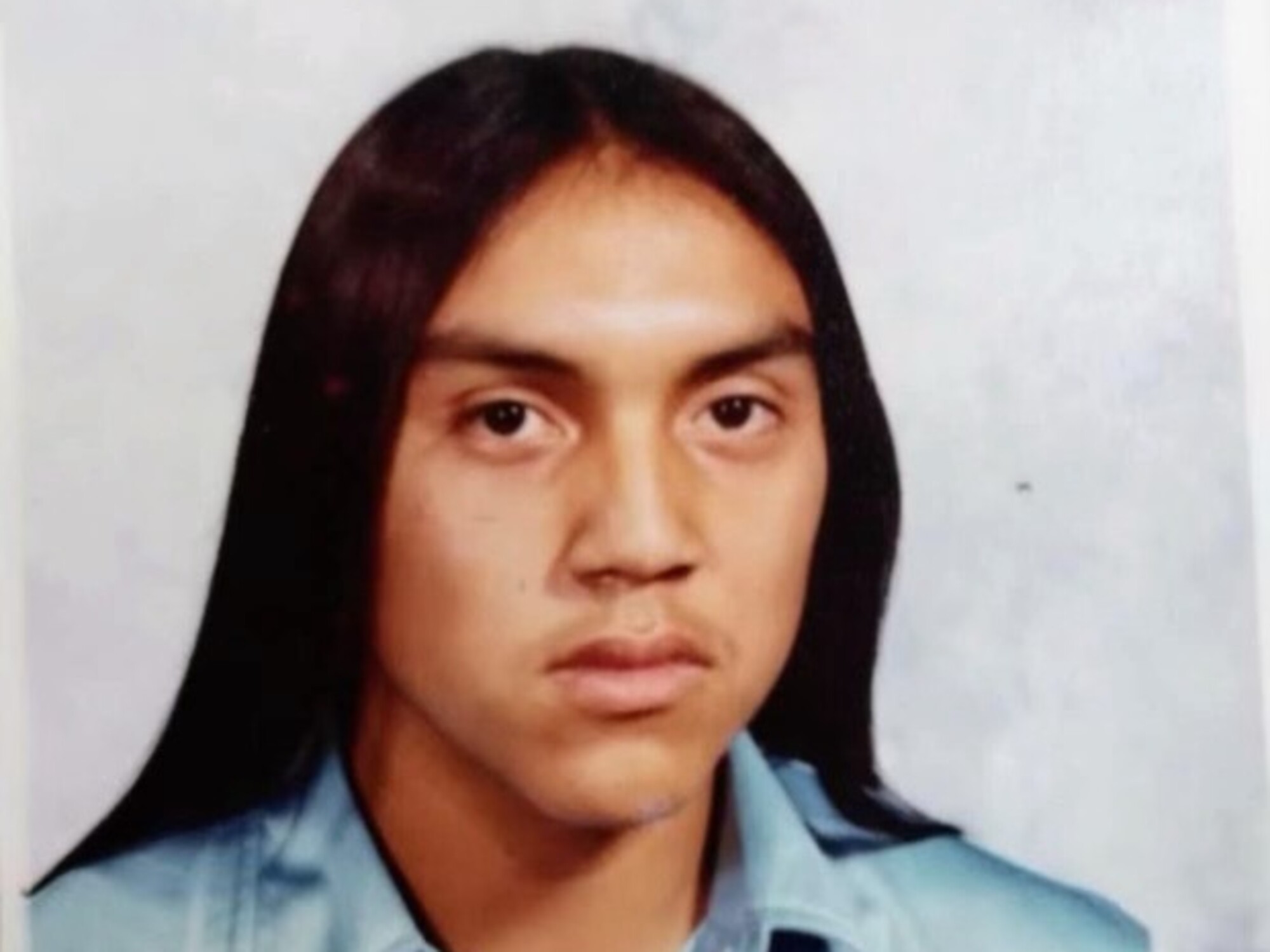

Joseph and family

Joseph and family

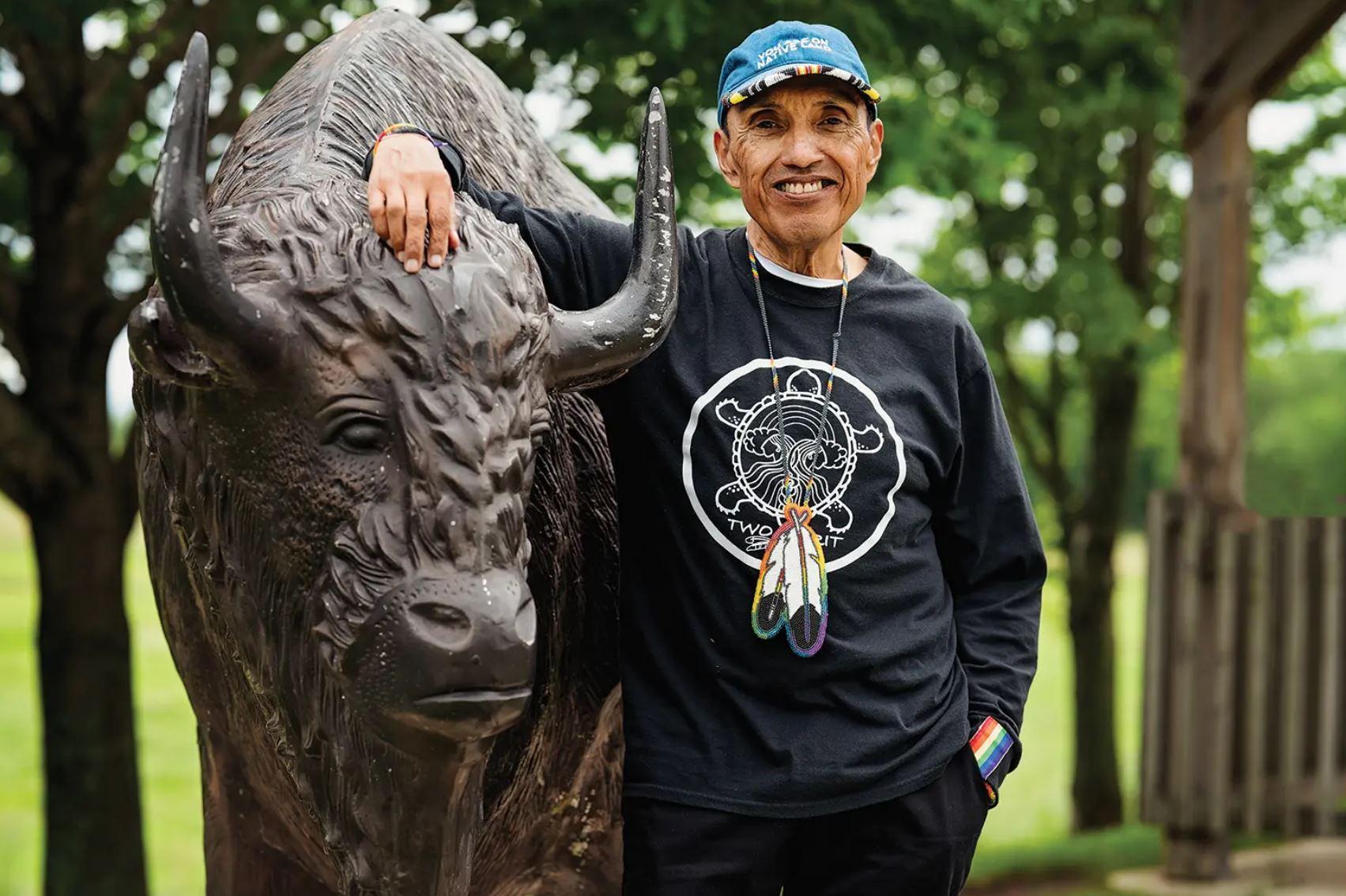

Joseph today

Joseph today

Respect at last

In eighth grade, Joe had a teacher that he often clashed with.

The teacher was also the school’s basketball coach, and Joe viewed him as a “total jock.” One day, the teacher finally asked Joe, “Why do you give me such a hard time?” Joe told him if he wanted respect, that he had to give respect. Joe was shocked that he and his teacher started to get along after that.

Joe remembers a history assignment from that teacher where he had to write an essay on the perfect society. Joe wrote that he wished “there were no white men who arrived to take all of our land and exterminate our people.”

Joe did not get his assignment back when the essays were handed back to the students with their grades clearly marked. Instead, the teacher simply said, “Please see me after class, Joe.”

All the students said “Oooohhhh” in unison because they thought Joe was in trouble. The teacher handed him his essay back with an “A;” he just wanted to tell him he did a good job.

Joe marveled at how his teacher had changed over the year. He thought he was cool because he actually listened to Joe and he felt seen by someone he did not expect to see him at all.

First kiss

In high school, Joe became very interested in fashion. He was always worried about his presence and overall appearance. Joe noticed that he paid more attention to his appearance and seemed more concerned about it than his peers were.

When Joe was 18, he had his first same-sex kiss with a 19-year-old. He thought he was his friend and gay, but the kiss was interrupted, and the next time Joe saw this friend, the friend’s attitude toward him had changed. He informed Joe that he really liked him but did not want to get AIDS.

He kept grabbing to hold Joe’s hand, which Joe found very confusing. Joe’s first kiss wasn’t what he had hoped for. Instead of butterflies, he felt confused and hurt. Joe didn’t know what AIDS was at the time, but the experience left him rattled. Joe decided to stay in the closet for a few more years.

First gay bar

After graduating from high school, Joe decided to attend UW-Stout, focusing on Hotel and Restaurant Management before changing to fashion merchandising. He attended for five years, ultimately not finishing his degree.

After college, Joe came home and remembered how much he loved to visit Za’s in Green Bay. It was the first gay bar he ever checked out. At the time, lip sync was really big, and he decided to enter a contest. He became hooked and kept entering contests because it was so much fun!

Eventually, after honing his craft, he moved out of state and started winning lip sync contests. Joe had felt connected to the queer community, but did not feel that connection at home on his reservation in Oneida.

Joe's graduation day

Joe's graduation day

An important move

He moved to Minneapolis with the purpose of embracing the queer culture and experiences that he got a taste of when visiting friends there. Joe got a job at the Mall of America as an Assistant Manager at Wilson’s, which led to working downtown at Banana Republic.

He loved that he was able to be himself in Minneapolis, and he often went dancing at the clubs. Sometimes, he even danced as a backup dancer for drag queens he knew. The music and club scenes were such a prominent piece of LGBTQ culture. Joe recalled, “People didn’t care what nationality you were or if you were gay. They didn’t give a shit. It was the freedom I craved and had wanted for so long.”

A favorite memory of Joe’s time in Minneapolis was, “When the AIDS fundraiser came to Minneapolis (event was precursor to AIDS Walk), there was a dance-a-thon on First Avenue at a bar called Quest. It was Prince’s nightclub and where the movie Purple Rain was filmed. The dance-a-thon was on the first floor of the club. At the time, I was dating a guy that worked for Prince. I raised $700 and danced nonstop for over four hours. My colleagues from Banana Republic came out to watch. The donation was matched dollar for dollar.”

Joe lived in Minneapolis for 11 years. Eventually, he moved back home to Oneida. It was a reluctant move, but a necessary one due to employment issues in a shaky retail economy in the aftermath of September 11, 2001 attacks.

Stereotyping

All of his life, he had been mistaken for being Mexican because of his last name. Usually, he did not bother to correct it. A common phrase he heard from others, unasked, was that he had a unique look, and he looked “old world.”

Joe never understood that and remarked, “I’ve heard it both ways—that I’m not Native-looking, not Mexican-looking. I always felt uncomfortable when people tokenized me when they found out I was Native. Suddenly, all interactions with white people brought up some Native stereotype.”

Joe was asked, “What do you do? Play bingo? Burn sage?” Joe became annoyed with this line of questioning. Reflecting on this, Joe said, “White people don’t know how to act around natives. It was like I was the last unicorn.”

A life-changing introduction

It was around 1990 when Joe met a roommate’s friend that was in Minneapolis visiting from Texas.

Upon meeting Joe, the friend exclaimed “Oh, so you’re two-spirit” after learning that Joe was a Native gay man. Joe had never heard that term before and brushed it off as “just another white person telling me what I am.”

For his birthday that year, the friend from Texas gifted him a book that opened his eyes to a hidden queer history he had never heard about before. The book was The Spirit and the Flesh: Sexual Diversity in American Indian Culture by Walter Williams.

Joe read the book from cover to cover. In it, he learned how Native Americans had much diversity before colonization. He learned that queer native people were known by different names in different tribes and often held places of honor within their tribe. For those who lost their language due to colonization, some modern Indigenous folks had adopted the English term “two-spirit.”

As Joe read the book, he experienced a mixture of emotions: sadness about a lost way of life he would never know, and anger that it was taken away from him and his people.

Reading that book changed his life. Joe felt empowered.

Coming out

Shortly after reading that book, Joe was dumped on his birthday by his boyfriend.

Emboldened by the passages in the book, anger came flooding out of him from trying to hide the fact he was gay his entire life. Joe said it was in this moment that he vowed to not back down or apologize for who he was. Previously, he had felt terrible that he had not told anyone in his family that he was gay.

It took the birthday breakup and reading an impactful book to change all of that. Joe decided to come out individually through handwritten letters to his family members. He called his older sister Linda to follow up with her.

Linda informed Joe that she and their sister Joanne had been waiting for some time for Joe to come out and tell them. Joanne was supportive to Joe after she read his letter. She told him that she had known he was gay for many years and was waiting for him to say something. Joanne thought it was funny that Joe believed he had hidden it so well. Joanne had also told her kids that their uncle was possibly gay and that it was not a big deal. Joe’s sister Judy responded to his letter and told Joe that she would love him no matter what.

Joe came to learn how fortunate he was when he came out to his family. They were so supportive. In time, he learned that other Natives that came out to their family were threatened with being disowned or with assault, such as running them over with their car.

Two-spirit presentations

Around 2015, Joe met an Indigenous woman who became a dear friend: Kat Werchowski. She was giving a talk at UW-Oshkosh on two-spirit people. It was the first time Joe had seen a presentation on two-spirit and it was being presented by two wonderful Indigenous folks, Kat and Mark Denning. Joe hosted additional two-spirit presentations and events through partnerships with the Oneida to assist with getting things going.

Joe was transfixed from the moment he saw the two-spirit presentation at UW-Oshkosh. He was a man on a mission to have Kat come present in Oneida. In 2016, Kat presented at the store Joe was working at, Turtle Island Gifts. Joe told Kat how much he wanted to present on two-spirit and let people know about this important-yet-hidden history. Kat encouraged Joe to pursue his passion, and so a seed was planted.

In 2021, Joe presented on two-spirit at the UW-Green Bay Middle School and High School Pride Camp. It was a hit with the students. Joe had re-enrolled in school at UW-Green Bay in hopes of finishing his undergrad degree. During his time in school, Joe worked as a Pride Center Intern in the UW-Green Bay Pride Center and as an Intern in the First Nations Education Office. Joe mentored fellow students in the Pride Center and the First Nations Education Office. During this time, he honed his presentation on two-spirit people and also made a permanent window display educating folks about two-spirit people for the Pride Center.

In 2021, Joe hosted a PBS documentary night for Two Spirits, a film about Fred Martinez, a young Navajo who lost their life because of being gay. Afterward, Joe debuted his new two-spirit presentation and had a Q&A panel with his nephew, Dr. Cory Carline. His friend Kat surprised him by coming to his presentation. Joe was floored that she drove all the way down from Superior, to his presentation at UW-Green Bay.

After the presentation, Kat took her two-spirit medallion from around her neck and placed it around Joe’s neck and told him, “Remember when you said it was your dream to do this? Now you’re doing it. Wear this whenever you do a presentation—it has everything in it that you need.” Joe thought it was probably the most precious gift anyone had ever given him.

“It was hers. It was like passing the torch when she gave me her medallion. Kat designed it, and it has medicine in it: Sage, sweetgrass and cedar. We both started crying,” he recalled.

Proud graduate

Joe fulfilled his goal of graduating and finished his undergrad at UW-Green Bay in 2023, becoming a proud first-generation college student.

In June 2023, Joe returned to UW-Green Bay to give his two-spirit presentation at the middle and high school Pride Camps. In the middle school camp, one young Oneida camper shared that they were excited about Joe’s presentation. They asked if they could perform a medicine dance known as the Jingle Dress.

Joe was overcome with gratitude. He had always wanted to have a dance incorporated into his presentation, but he was not sure what that looked like. After Joe finished his presentation, the student put on their regalia and performed a jingle dress dance for the entire camp.

The entire camp watched mesmerized as a young two-spirit Oneida filled the room with absolute queer joy. Joe teared-up and honored him by dancing at the end of his presentation.

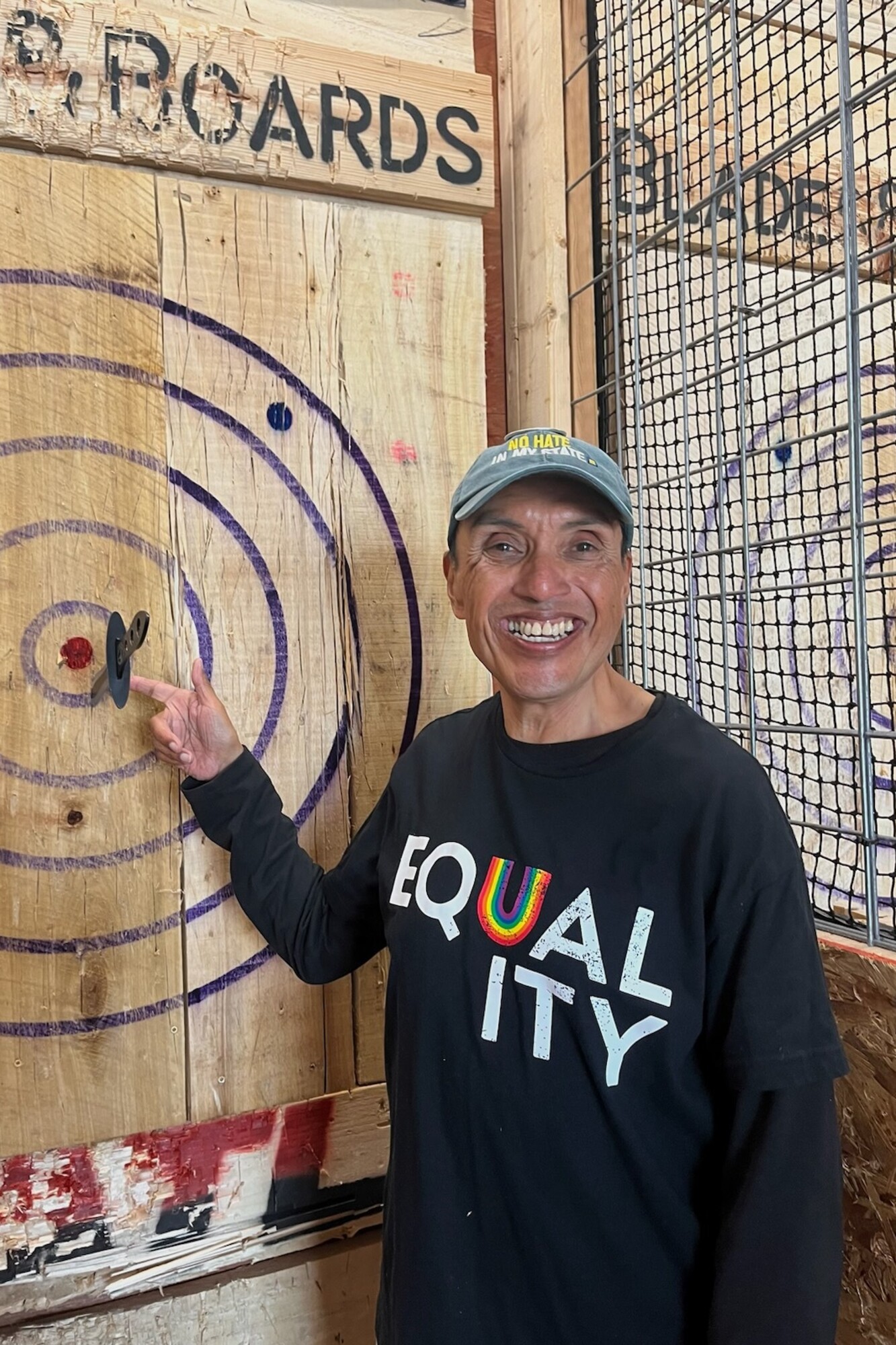

What has changed, what has not

Joe said, “One thing that has changed about the queer community is that bars don’t seem to be the popular space to meet as much anymore. Not as many people in the community drink. Green Bay has improved with offering other things to do. There are places like the UW-Green Bay Pride Center to visit, too. Sometimes, there is still that feeling of competition among gay men. It’s hard to be platonic friends with someone when you’re in a committed relationship, as there is always jealousy from someone.

“Also, there is definitely still a lot of insecurity due to the current political environment,” Joe added. “People are getting afraid to be who they are. Gay bashing was prevalent growing up, and it seems to be coming back. Some people are bragging because of Trump and the anti-LGBTQ bills being passed around the country."

"The LGBTQ community needs to come together and stand up for our rights. We also need more allies to be vocal about it, too. We all need to work together—it’s all or nothing for all of us who are marginalized. And, we all need to respect one another—no one is better than the other.”

Pride parade presence

Looking to the future, Joe is excited about collaborating with other organizations like the Bay Area Council on Gender Diversity and the Bay Area Trans Youth Alliance.

Martha Marvel invited Joe and fellow two-spirit folks to march in the Milwaukee Pride Parade on June 9 of this year. All together about 20 two-spirit people marched—among them were Oneida and HoChunk.

Joe was surprised how many voices called out to them as they marched along the route and announced their tribal affiliation like the Anishinaabe and HoChunk. Joe and his fellow two-spirit marchers called back in their best war cries. By the end of the route, Joe had practically lost his voice.

Two-spirit 101

Joe wants everyone to know that the term two-spirit originated in 1990 as an umbrella term for natives to use to describe a gender non-conforming third gender. This term is useful for Indigenous folks to use to identify themselves. Due to colonization, some tribes lost their language, and thus the term for the two-spirit in their tribe. The Oneida are currently working to find their term.

Joe also wants people to learn about Native history and the Native queer history of the folks whose land we all reside upon, which was originally called Turtle Island.

Joe offered these parting words of advice: “Be your authentic self. If you live in a community or a family and you can’t be out, find your support. It’s not always easy to do. You are special. You do matter, and there is definitely a place for you in society.”

He said, “If you are not Native, please do not use the term ‘two-spirit.’ Non-Native LGBTQ folks have plenty of other terms to claim.”

Photo by Melanie Jones of Our Lives Magazine

Photo by Melanie Jones of Our Lives Magazine

recent blog posts

December 17, 2025 | Michail Takach

December 16, 2025 | Michail Takach

December 01, 2025 | Dan Fons

The concept for this web site was envisioned by Don Schwamb in 2003, and over the next 15 years, he was the sole researcher, programmer and primary contributor, bearing all costs for hosting the web site personally.