Jerry Dreva: shattering the status quo

Jerry was born in South Milwaukee, Wisconsin on January 8, 1945 to Margaret Andreska (1923-1996) and Edwin Dreva (1916-1985.) He shared a birthday with his idol, David Bowie, as well as Elvis Presley.

Jerry grew up across the street from the old South Milwaukee library on Michigan Avenue, and he spent many hours there learning, dreaming, and scheming for his future.

Jerry was already an activist and organizer at an early age. He was invited to attend the inauguration of President John F. Kennedy in 1961. As a teenager, Jerry fanned the flames of the anti-war movement, spray-painting Vietcong flags on mailboxes and writing political graffiti on walls.

On April 2, 1964, he was interviewed by the Milwaukee Sentinel after organizing a George Wallace picket at Serb Memorial Hall. Although the hall filled beyond capacity, with 550 attending and over one hundred turned away, the opposition was heard equally loud and clear. Jerry recruited eighty-five picketers – the largest protest Wallace faced in his campaign – to carry signs reading “Keep Milwaukee Clean, Vote No for Wallace.”

Through his involvement with Congress of Racial Equality (CORE,) Jerry met Barbara and Morgan Gibson, who introduced him to the local counterculture, equality, and liberation movements.

Jerry attended St. Mary’s Catholic School and St. Francis Seminary Prep School. Father Joseph Feldhausen, later of Gay People’s Union and St. Nicholas Parish, was part of his senior class. Although he’d planned for a life in the priesthood, Jerry was expelled for having radical views and denied his priestly vows. He would later say, “all he got out of seminary school was four years of Latin and no driver’s ed.”

Jerry moved to Collegeville, Minnesota to attend St. John’s University, where he obtained a Bachelor of Arts in English. While attending, he became fascinated with the Avant Garde works of Susan Sontag, John Cage, and Buckminster Fuller. He met Ben O’Loughlin of Los Angeles, and the two became lifelong friends. When Jerry got a teaching fellowship at UW-Milwaukee, Ben naturally followed.

“Students hated English, so I made each day a celebration,” said Jerry. “No matter what you’re teaching, you transcend what you’re teaching, and you teach yourself in the process.”

In fall 1969, Jerry and Ben moved to the Gibson family farm in Plymouth, Wisconsin, with the intention of splitting time between the country and city. When the plan fell through, they briefly stayed at the Gibson home on Maryland Avenue.

“Barbara Gibson taught me the importance of using material from your own life to spin your work,” said Jerry. “Self-exposition: the courage to tell secrets. In her work, she tries to integrate sex and politics and art with unity. Life and work as a whole cloth.”

Jerry and Ben attended the Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in September 1970. While attending, Jerry helped author the Gay Liberation Front’s statement of support for Huey Newton, after the “Letter from Huey to the Revolutionary Brothers and Sisters about the Women’s Liberation and Gay Liberation Movements” was published in The Black Panther.

After meeting Doug Batts of NYC Gay Liberation Front, Ben decided to attend the Second RPCC in Washington D.C. two months later. Inspired by the solidarity, ferocity, and courage of the movement, Jerry joined other Milwaukee youth in forming a local chapter of Gay Liberation Front to shatter the status quo.

Jerry had been starving for real radicalism, finding the local gay rights movement “square,” stale, and nowhere near heavy-handed enough. And now he’d found them.

Ben decided to move to New York City and asked Jerry to join him. Jerry declined, choosing to stay with the Gibsons. Ben departed on January 1, 1971.

The next day, Jerry joined two dozen youth marching down Wisconsin Avenue in Milwaukee’s first gay liberation parade. The January 1971 issue of Kaleidoscope was a “Gay Takeover” by Gay Liberation Front and the Radical Queens, who debuted in a double-page blow-up centerfold. The march was just another expression of the revolutionary mood of that moment.

Jerry met Bobby Lambert, a student in Barbara Gibson’s creative writing class, while attending the protest.

“On January 2, 1971, a friendship began that would grow and last until the end of Jerry’s life,” said Bobby.

Jerry had spent a summer in London, where he saw a life-changing pop art exhibit and became obsessed with Andy Warhol. This has a tremendous influence on his artistic expression.

“Warhol was the first person in our time who became more important than his work,” said Jerry.

Soon, he met some of the local queer kids who would later become Les Petites Bon Bons. He began making collages and rubber stamp artwork – including the limited edition “rainbow colored cock prints” later to become Bon Bons calling cards. Christopher Isherwood and William Burroughs were among Jerry’s earliest recipients of correspondence art.

“A few months later, I got a desperate call from Jerry, miserable at being back home,” said Ben. “I went back and drove him to New York City. Jerry, Doug, and I lived together in a third-floor walk-up on Avenue C at 6th St, stepping over the occasional junkie passed out on the stairs. Doug and I worked at the GLF Community Center in an old firehouse in the Village -- while Jerry spent most of his time doing street art and loving New York City.”

In April 1971, Bobby Lambert joined the collective in New York City for a few weeks. They became active groupies of Andy Warhol and the Factory scene. But eventually, the money ran out and Bobby went home in June 1971. A week later, a letter arrived from Jerry – the first in a series of correspondence that lasted over 25 years.

“Went to Jackie Curtis’s play Vain Victory at La Mama. Yoko Ono and John Lennon arrived with Andy. I reached into my purse and whipped out my trusty dayglo kisses. Gave kisses to Andy, who looked confused and said thank you; gave kisses to beautiful Yoko, who liked them more (than mechanical Andy) and showed them to others; but when I tried to give them to John, he said, no, I do not give kisses to straight men, at least not on this particular night. I sat one row behind them at the play. John looked bored. Fantastic free party afterwards at Max’s Kansas City.

Thus ends this chapter of my life. I’ll probably stay in South Milwaukee for a few weeks.”

That decision changed his life forever.

The Bon Bons are born

Despite the landmark 1971 Santilli ruling that the State of Wisconsin could not govern what people wear, police harassment of gender non-conforming people continued for years. Arrests, violence, and even incarceration were real threats.

Seeking a new way to express artistic and intellectual ideals, Jerry and a circle of friends (Bobby Lambert, Chuckie Betz, J.P., Mark Slizewski, Dick Varga, Gary Pietrzak, and Jim Sullivan) became “Les Petites Bon Bons,” a conceptual group of social influencers who were suddenly everywhere. The name, coined by Dick Varga, was intended for a theatrical review planned by the Radical Queens – which, like so many Bon Bons projects, never actually materialized.

“I didn’t know whether ‘Bon Bons’ was a masculine or feminine word. I just put the E in there for gender confusion,” Jerry said.

“The highly politicized gay period gradually gave birth to Les Petites Bon Bons,” said Jerry in 1980. “The Bon Bons were an overtly gay band of cultural revolutionary guerillas. We did not abandon our radical politics, but began to realize that conventional radical politics were, of their very nature, an anti-gay medium, or at least un-gay if not anti-gay. We began to feel that a new synthesis of art, politics and sex was needed.

The entire concept of lifestyle as art, that I champion and that I saw as the art of the future, was formulated at that time. I owe a great debt of gratitude to Bob Lambert, Chuckie Betz, and the other Bon Bons who helped me formulate these concepts that inform all my work.

In many respects, the Bon Bons were the purest expression of the life/art concept. We were famous for being famous -- rather than for doing anything in particular. We were the world’s first and greatest conceptual rock and roll band. We were grand chameleons who changed costumes and hair color to suit the occasion. We joyfully celebrated life in LA and created our lives as works of art. We understood our lives and our art as revolutionary aspects of being gay. We defined gay much more in terms of liberated and liberating lifestyles than in the limiting terms of sexual identity. Straight meant rigid, unyielding, moribund, while gay meant diversity, flexibility, openness, change.

What I really learned from the experience – was the power of the media to create, define and distort reality. The media had a field day with the Bon Bons. They used us and we used them. In a sense, the Bon Bons were a media creation. The papers and magazines defined us to the public because we refused to do so. From the beginning, we didn’t want anyone to be sure of who or what we were. My life has never been the same since.”

The Bon Bons exploded in popularity after a 1971 photo shoot with the legendary Francis Ford. Inspired by a Rolling Stone story about the Cockettes, Ford sought to photograph local drag queens. A mutual friend, John Stegman, introduced them to the group. They brokered a deal: Ford could take photos, if he produced prints the Bon Bons could use to promote themselves.

The photo shoot led to a juried competition at the Milwaukee Art Museum, which the Bon Bons showed up for without tickets. When confronted with a half dozen queens in bizarre costumes – including Chuckie Betz on stilts in a transparent gown that lit up when plugged in – the registration table turned them away. Outraged, Ford told them he’d remove all his artwork and leave if they weren’t admitted.

“My mom was talking to a guy in a Green Bay Packers sweatshirt when Chuckie walked by,” said Ford. “He said: where did THAT one come from? And my mom said, ‘Hey, that’s my son!”

The photo shoot energized and motivated the Bon Bons’ correspondence efforts. They sent artistic care packages to everyone from Andy Warhol to Rona Barrett. While many did not respond, they did receive academic applause:

- Jack Burnham, art department chair at Northwestern University, responded “…more power to you and Les Petites Bon Bons. Culturally, you’re part of the wave of the future, and if you can get it out into the street and make the little people think, you’ll be doing something that museums just can’t do.”

- Arthur Bell, who reported on the Stonewall Riots, replied “should you come east one of these days, do say hello. Meanwhile, blow those bubbles my way. I’ll blow mine back.”

On May 21, 1972, forty Le Petits Bon Bons posters were hung around the St. John’s University campus at midnight. Jerry remembered a freshman asking him, “where are those guys from?” to which he answered “Milwaukee.”

“Well, what do you they do?” “Nothing.”

Little did they know how much “nothing” was about to happen.

California calling

Ben O’Loughlin decided to move back to Los Angeles, where his childhood friend Richard Cromelin was now a rock reporter. Thrilled by stories of the Bon Bons, Richard insisted they come to California.

On May 29, 1972, Jerry left for Los Angeles. “Even Hollywood would never be the same,” said Robert Lambert. Richard had the access. Jerry had the ambition. And Los Angeles was their stage.

“I’m just smack in the middle of the whole rock and roll scene and it’s just maddingly fantastic,” wrote Jerry on June 8, 1972. He met Gronk, a founding member of the Chicano arts collective Asco, later that summer at “Butch Gardens,” a Chicano gay bar in Silver Lake. At other L.A. gay bars, Gronk was often the only person of color. The two formed a life-long mutual appreciation, friendship, and partnership.

Bobby moved to Los Angeles in January 1973. Within 96 hours of his arrival, his photo outside Rodney Bingenheimer’s English Disco was printed in a rock and roll magazine over the caption “This is Los Angeles.” The photo was syndicated worldwide through UPI.

Overnight, Les Petites Bon Bons became the most famous glitter rock group that never cut a record. And suddenly, somehow, the Bon Bons had backdoor access to the hottest spots in Los Angeles.

They were expert self-promoters who turned up in all the right places, sported all the best looks, and knew all the right people. The Bon Bons fed an all-consuming media hunger for out-of-control youth, celebrity, and glamour. They may have been young men from Milwaukee’s South Shore, but they expertly manipulated the Hollywood star-making machine into making them famous. In many ways, they were the world’s first social influencers, appearing in the Los Angeles Times, People, Newsweek, New Music Express, Interview, Melody Maker, Creem, The Advocate, and other magazines. They were regulars at Rodney Bingenheimer’s English Disco, cavorting with the likes of David Bowie, Iggy Pop, Lou Reed, Elton John, Divine, the Cockettes, Sylvester, the New York Dolls, Mott the Hoople, Paul Lynde, Linda Lovelace, Cherry Vanilla, Sable Starr, and more.

It didn’t hurt that Lisa Rococo, the nightlife columnist for Phonograph & Record Magazine, was their good friend Richard Cromelin’s pen name. “Lisa’s” carefully planted stories triggered a serious fear of missing out for Sunset Strip youth – all of whom wanted to know the latest sensation.

In April 1973, Lisa ran a Bon Bons photo with the caption, “Would you put us in your magazine if we wore dresses?” Readers were asked to identify them, and despite guesses including everyone from Alice Cooper to Bette Davis to the Beach Boys. Only thirty-nine readers guessed correctly.

The Bon Bons were known for the “packages” they sent to visiting rock stars at their hotels. These elaborate collaborations went far beyond press kits. They were a form of ritual sacrifice to pop culture – and their ticket to being known, recognized, and favored by all the right people. “We are the surprise in your crackerjacks,” they bragged.

After hanging out with the Bon Bons several times – including the time Jerry and Bobby hijacked a Meet David Bowie contest at Union Station – and receiving multiple packages, Bowie included the words “Bon Bon” on his “Ashes to Ashes” record cover.

On January 2, 1973, the Bon Bons Anti-Manifesto was released in queer zine Gay Sunshine. Only eight thousand copies were published.

“Les Petites Bon Bons are becoming famous, that is, coming to understand more fully each day that we have always been famous. And so have you,” wrote Jerry “Jeri Bon Bon” Dreva.

“Although this group didn’t really play as a band, they were included in media stories and captured in photographs. By foregrounding the construction of stardom, they intended to expose and critique the media’s superficiality,” wrote Max Benavidez in 2007.

Although they had no musical abilities and had never played a concert, Jerry and Bobby encouraged the notion within rock reporter circles. Were the Bon Bons a rock band? A polyamorous cult? A queer crime ring?

The Bon Bons weren’t telling. “We are everything you think we are and more,” they replied.

“To hundreds of thousands who saw our photos, the Bon Bons became the personification of the drag rock era, and later, the proto punk era,” said Jerry in 1980. “We were court jesters for rock and roll royalty; we were artists-in-residence for the glitter scene.”

“I had always told friends in Milwaukee that if you wanted to be famous, all you had to do was look like you were,” said Robert Lambert. “It shocked me to find out how true that was, even in Los Angeles.”

Jeffrey Alan Hunter featured his “Bon Bon mot” in GAY INSIDER USA, published in 1972:

one of the most spirit-lifting pieces of ’72 came from a Cudahy group known as Les Petites Bon Bons… the envelope was pasted up with a N.Y. skyline postcard and cherry and reindeer stickers. Zip code was 5311OH!

Then, inside, the photo of a cluster of gorgeous gender defiant freaks made my heart leap up and warmed The Cockettes of my heart.

Les Petites Bon Bons asked for nothing, gave no prosaic explanation of who they are, just three lovely pages of super-identifying one-liners, quotes, lyrics, and well, let me share a few:

“We have no art. We have only life which is one and gay. LPB erase the straight line between life and art and give you ecstasy. LPB are both carrion crow and the rising phoenix, soon to become the bird of paradise. We don’t believe in positions. Gay people have a responsibility to sabotage seriousness (Charles Ludlam.) Meaning is not in things but in between (Norman Brown.) There’s room on the Bon Bon cloud for anyone who wants to move from work to play, from productiveness to receptiveness, from security to the absence of repression, from delayed satisfaction to immediate gratification, from the fetishism of commodities to the erotic science of use values. To dance is to live (Isadora Duncan.) We aim to radiate power not possess it (Henry Miller.) Everything we do is music (John Cage.) By having fun, we are fighting the straight man’s inebriation with death. Our lives are our art. Our art is our politics. Our politics is the way we make love. We are poets and we are dancers. LPB is the name of the play, a group of rock musicians, a gay twirling corps, a traveling circus. We are the $64,000 question. Everything they say we were, we are – and lots more they haven’t even dreamed of yet.”

My dears, I have you on my wall, I hope you don’t mind. You have immortalized yourselves. There was a star danced, and under that, you were born.

The Bon Bons attended the August 11, 1973, premiere of American Graffiti with star, friend, and follower Mackenzie Phillips. Their Log Book noted a bittersweet turning point: “the film was a fitting farewell to the glory that was Bon Bons. The next morning, they woke up on their way home, young boys with quite an adventure behind them.”

A media creation from beginning to end, the Bon Bons never had agents, never had bookings, never had performances of any kind. They were simply there.

Until they weren’t. While it was easy to maintain Bon Bons access with two or three members, it was impossible to pull off the operation with seven people. In addition, some of the Bon Bons’ guerrilla antics in Milwaukee caught up with them in Los Angeles.

“One morning an FBI agent showed up at my door,” said Bobby Lambert. “I answered wearing a hooded red devil robe and having just smoked a joint. It was not a comfortable conversation.”

The Bon Bons’ last great hurrah was the Decca Dance on February 2, 1974. The event, held in the Elks Lodge Ballroom in downtown Los Angeles, was an awards ceremony celebrating the one millionth birthday of art. Over eight hundred people attended. Oingo Boingo, then just emerging artists, played a full set. Artist collectives and correspondence artists from all over the world were meeting face-to-face for the first time. Some guests, invited to a special pre-party, we deliberately misidentified – and challenged to unravel who each other really was

Jerry Dreva attended in cholo drag as El Bon Bon, Chuckie Betz went as Edible Bon Bon in an outfit made entirely of real candy, and Bobby Lambert went shirtless in leather, denim, handcuffs, chains, with a fresh beef kidney around his neck that he later beat himself with.

The Bon Bons had their final collective interview soon afterwards, in which they hinted at reinvention:

People will write captions under our photos and say were’ the latest drag rock sensation in LA when we’ve never given anyone any reason to suspect we are a band.

We’re discovering what it is we are and what other people think we are. Very often we’re outraged when we find out what they think. We hear that we’re so decadent—I’m not decadent, or a junkie, or jetting around the world. It’s total media fabrication.

The Bon Bons are not specific. They’re never specified on the guest list because they never know who’s going to show up under that name. Bon Bons is the magic name here. Sometimes we’ll show up at parties and someone has already gotten in under that name and we can’t! We like that.

The Bon Bons think their next period will be “post-cultural.” We feel mystical about our futures; we’re confident—yet we’re here on borrowed time. We’re always ready for a change. To expect us to be in the glitter, was a challenge to change… we can’t go to The Outcast in glitter.” – interview with Count Fanzini, spring 1974.

The group, now known as Yesterday’s Bon Bons, began to drift apart.

“The whole scene was punk by then,” said Bobby Lambert. “Within two weeks, I completely changed my look -- and you can see it in the photos. The world changed extremely fast, and everything was suddenly quite different. I cut off all my hair, changed my clothes, and started going to leather bars. And that was two weeks after my hair was still big, wild, and bleach blonde.”

“People thought they knew who we were, and we had to change that, because we never wanted anyone to be right about what they thought we were. The whole mythology of the Bon Bons was, ‘whatever you think we are, we are, except, not.’”

“It was a great time, but it was over,” reflected Jerry in 1980. “Great eras can come and go in five years.”

Home again

Jerry returned to Milwaukee in 1974 to continue his artwork while working as a reporter for the South Milwaukee Voice Journal. At times, these tracks collided in remarkable and unexpected ways – in both Wisconsin and California.

Some of his ground-breaking art events included:

- Art Gangster. In 1974, Pablo Picasso’s painting “Guernica” was vandalized at the Museum of Modern Art. Artforum Magazine received a curious piece of anonymous mail art afterwards, with the phrase “ART GANGSTER” stamped on a related LA Times news clipping with the numbering 14/50 below it. Forty-three years later, Gallery 98 confirmed this was the work of Jerry Dreva.

- The Hartman-Smith Presidential Campaign.

Jerry decided to liven up “the boring presidential election in history” with a mail-order campaign supporting a Mary Hartman / Patti Smith ticket. During her Milwaukee concert, Smith accepted the nomination of “president of vice.” On March 6, 1976, Patti Smith performed at the Oriental Theater, where she accepted the nomination -- if she could be the "president of vice" and not the vice president. (March 1976)

- Bicentennial Self Portrait. “What better place to celebrate the Bicentennial than in the Kmart photo booth in Cudahy, Wisconsin?” asked Jerry. In a series of sixteen patriotic photo booth strips, he posed in various stages of undress with images of dead presidents. He was threatened with arrest and permanently banned from the store. (July 4, 1976)

- Scott Johnson Fan Club.

Jerry created a fake mail-order fan club to honor a 24-year-old college graduate (Patrick Lajko) who disguised himself as a high school student and became a star gymnast in Wichita, Kansas. (December 1976)

- Correspondence Art Show. Jerry showcased his work at the Broadway International Post Card and Mail Art Extravaganza at Billy Curman’s Broadway Galleries (730 N. Broadway) (March 20, 1977)

- Art Meets Punk. Over 1200 punks invade Jerry’s party at LACE Gallery in downtown Los Angeles, which is seized by the police force. Musical guests include the Bags and the Last. (March 1978)

- Dreva/Gronk 1968-1978: Ten Years of Art/Life: Jerry and his long-time partner Gronk co-produced a one-night retrospective of their first decade of friendship.

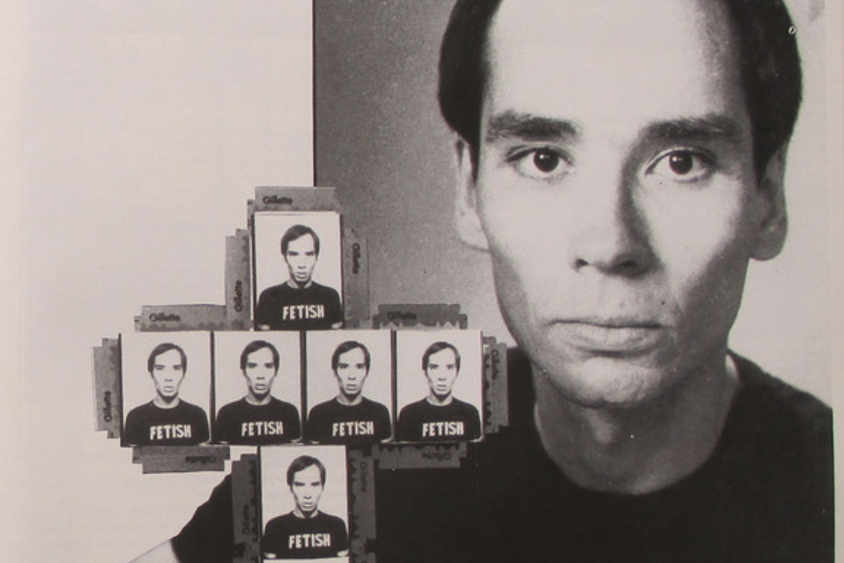

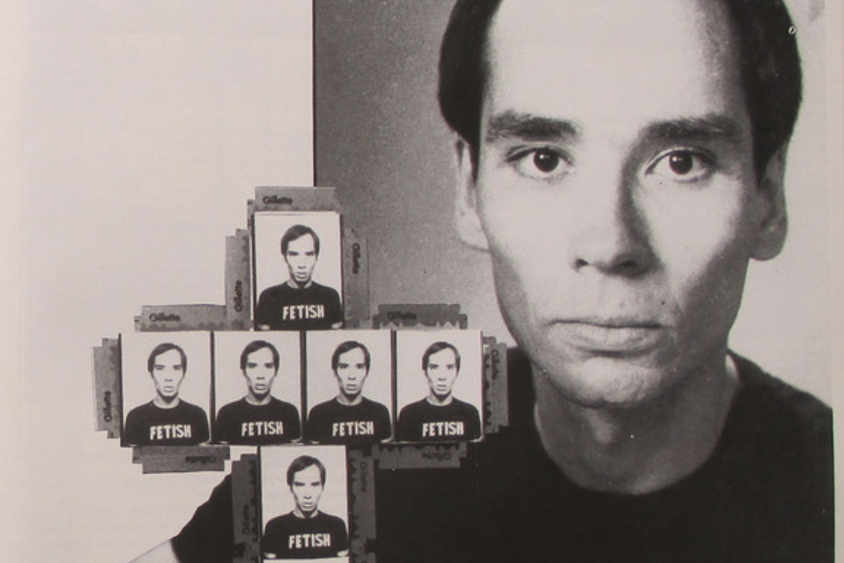

- Razor Crosses. The Milwaukee Journal dedicates a half-page story to Jerry’s “ritual crucifixion, 1978 style” at the Water Street Arts Center (1247 N. Water St.) which includes red sanctuary candles, a pew kneeler, crosses made of dozens of photobooth portraits, within razor blade frames. Jerry says the crosses represent the eternal cycle of life, death, and resurrection. “Creating the self is the only significant art form left in the 70s,” proclaimed Dreva. (June 1978)

- Dreva at 33-1/2. Celebrating his 33-1/2 birthday, Jerry publishes photos of lifelong friends while punk bands The Lubricants and Ruthless Acoustics play. (June 1978)

- Heart Attack. Between 1 a.m. and 4 a.m., Jerry secretly covers the wall of the crumbling Grant Park Beach House with hundreds of multicolored Day-Glo hearts. The same building was painted with Day-Glo stars in summer 1975. Since his identity was unknown, Jerry reported on his own renegade art installations in the South Milwaukee Voice Journal. It would be years before his identity was discovered. In September 1978, a copycat spray-paints hundreds of hearts on the wall of the San Francisco Institute of Art. (July 1978)

- Homage to Tut. Jerry wraps himself in a shroud and places himself in a coffin outside a Milwaukee gallery. Photographs were syndicated to over five hundred publications. (August 1978)

After outing himself as the “Love is Virus” vandal in a 1980 High Performance interview, Jerry was charged with disorderly conduct and vandalism from South Milwaukee Captain Kenneth Berg. He was also suspected of spray-painting South Milwaukee High School with the message “Art only exists beyond the confines of accepted behavior” in August 1978. The public praised the artist’s work as “constructive vandalism.

Over the years, Dreva’s artwork was featured at the Museum of Contemporary Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and many independent galleries and exhibitions. As always, media coverage of Dreva’s work was repurposed as correspondence art.

“I cannot be defined or categorized as a gay artist as easily as I once was,” Jerry wrote in 1980. “I would not entirely reject that label, however. My homosexuality no longer occupies the central position in my life that it did ten years ago. Sex kind of seems to me little more than a bad habit. I am less interested in sex every day. As for love, I agree with Fassbinder and Burroughs that it is a virus, a crippling disease to be avoided at all costs.”

“Don’t label me a punk artist. However, I’ve used a lot of punk images in my work during recent years. Or is it S&M? I’ve felt close to a lot of the classic punk attitudes – high energy, spontaneity, rebellion, extremes of style, risk, and danger.”

California, revisited

In 1979, Jerry returned to California to produce a year-long series of exhibits celebrating the 200th anniversary of Los Angeles. He was inspired by the energy of the post-punk new wave scene, which manifested at venues like Madame Wong’s, Hong Kong Café, and Atomic Café.

“In 1972, there were no local bands, and if there were, they were playing high school dances in the valley,” said Dreva. “Now, there’s a great energy, youth and vitality to the music scene.” He was especially impressed by the emerging Chinatown scene at Hong Kong Café and Madame Wong’s.

Jerry had a deep appreciation for Los Angeles, especially the downtown he discovered in 1979.

“The downtown arts scene is flourishing, while the west side looks like a futuristic space station,” he wrote. “Main Street is like a scene from the 1950s. Harold’s Bar and the Waldorf are incredible places. The black drags queens are great – and the bars look just like John Rechy described them in City of Night. There is so much to celebrate in LA.”

While he hosted meals at The Original Pantry and Phillippe’s downtown, one of his long-time favorite hangouts was the Gold Cup coffee shop (6700 Hollywood Boulevard,) which he called “first rate theater.” The Gold Cup was a nationally known gay cruising spot – and, sadly, a beacon for teenage runaways. “The place is always swarming with pimple-faced low-rent hustlers who all sound like they just arrived from Oklahoma,” wrote Dreva. “The police are trying to close down the Gold Cup; the head waitress told me they are really serious this time.” (After appearing in numerous teen runaway films, including the infamous Dawn: Portrait of a Teenage Runaway, the restaurant finally closed in 1987.)

After the anniversary exhibit, Jerry taught English, contemporary theory, and avant-garde literature at Otis Art Institute. He was also a typesetter for the Los Angeles Institute for Contemporary Art’s Journal. He published over a dozen volumes of the “Seminal Notebooks,” thousands of pages filled with real semen and given away to friends and archives.

Full circle

In the mid-1980s, Jerry stepped away from art and music to visit Central and South America, where he became involved in local liberation efforts. He was a supporter of the Shining Path in Peru, but adamant in insisting that they include gay rights in their agenda. He was a long-time supporter and donor to human rights publications.

After a few years, he returned to South Milwaukee to care for his ailing mother.

“She was a doll, and they always had a strong relationship, so he took good care of her,” said Robert Lambert. “After all his adventures, this had to be a real change in his pace of life.”

After his mother’s death in November 1996, Jerry struggled with an extended manic period that compromised his overall health.

He visited friends Richard Cromelin and Sean Carillo in Los Angeles, making plans to return there and start a new life. However, he passed away the day after he returned to Wisconsin.

Jerry Dreva died of a heart attack on March 26, 1997, in South Milwaukee. He was buried in Holy Sepulcher Cemetery in Cudahy. He was only 52.

“Jerry was without a doubt the most brilliant person I’ve ever known,” said Robert Lambert. “I think it took a crazy person to see through the false veneer of how we all lived then, the senseless conformity and its unquestioned hierarchies of straight male power and privilege.”

“As with other radical activists of that time, he experienced lifelong bouts of mental illness. He was so enamored with the highs that the lows were, for him, a fair price to pay. Medication was never an option. He’d complained of heart abnormalities for some time, but never in his life would have considered going to a doctor.”

While only a basic obituary ran in the local paper, Professor Howard Singerman of the University of Virginia wrote a respectful remembrance in the Umbrella arts newsletter.

Editor Judith Hoffberg added, “Jerry was not supposed to die, because he was so full of energy, a hyperactive energy that overwhelmed you.”

As with many LGBTQ elders, Jerry’s estate was settled by relatives who neither understood nor appreciated his life’s work. As a result, very few of his original art pieces survive to this day.

“I am interested in mythologizing the mundane,” said Dreva. “In celebrating the daily and transforming the ordinary into the extraordinary through the magic and power of art. I made art in order to survive, in order to make sense of my life, to give significance and confer meaning upon it. My art is my life.”

"This is Los Angeles," 1973

"This is Los Angeles," 1973

recent blog posts

March 01, 2026 | Michail Takach

March 01, 2026 | Michail Takach

Randy Reddemann: building connections beyond the bars since 1976

February 28, 2026 | Bjorn Olaf Nasett

The concept for this web site was envisioned by Don Schwamb in 2003, and over the next 15 years, he was the sole researcher, programmer and primary contributor, bearing all costs for hosting the web site personally.