Jeremy was a loner in high school. As he explains, the town was full of jocks, and they loved to pick on the outsiders.

“I knew I would get in trouble if I fought them – not only at school, but at home,” said Jeremy.

“My stepfather would fight me because I fought kids at school. It is crazy to think this adult wanted to fight me. I learned that I could not fight the other students. So, I put one of them in a headlock, and he turned out to be the head of the basketball team. Since they could not expel him, they expelled me.”

Jeremy was placed in an alternative school. Later, he was the only student who ever exited the program well-adjusted enough to return to a normal school.

“I never thought, and I still do not think, that there was ever anything wrong with me. There was a lot wrong with my home environment. It was very, very dysfunctional.”

Eventually, Jeremy started running away from home. When he called the police on his stepfather, the police would put him in shelter care for “protection.”

“They weren’t protecting me,” said Jeremy. “They were putting me in an environment with other kids who caused trouble.”

“And here I am, this gay kid, trying to be butch, trying not to be bullied, and trying to survive. Eventually, I started running away from the shelter care. I went to Wisconsin Dells, where I told everyone, I was a college student, and they gave me a job and a place to live."

"I was doing pretty well for three months before they found out.”

Since the shelter system was not working, the state sent Jeremy to a juvenile detention center. He was legally emancipated when he was sixteen. His social worker convinced the judge to let him live on his own, and he’d already proven to them that he could be self-sufficient.

“This was the weird cycle of my childhood. A lot happened to me before I was even old enough to drive.”

Since neither of his parents graduated from high school, Jeremy was committed to finishing high school.

“I wanted to achieve something, and I wanted to prove to my stepfather that I was important,” said Jeremy. “I got to walk down that aisle and get my diploma in the end. That was a huge, huge achievement for me. I proved to myself and everyone around me that I could and would do important things in the world.”

Jeremy got involved with the Chicago rave scene, which was extremely rewarding socially and spiritually.

“This was a lifesaver,” said Jeremy. “Raves were a beautiful outlet for meeting queer people. I did not grow up with any gay people in my life. I could not go to bars since I was underage. But I could meet people my own age at raves.”

Big city nights

Jeremy came out when he was eighteen.

“I told everyone ‘I am gay’ and I left for Minneapolis,” said Jeremy. “I had this belief that gay people could only live in big cities. After a while, I moved to Milwaukee.”

“I had just finished high school and did not know what I wanted to do next. So, I went to college for photography at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Peck School of the Arts, and took a bartending job at Boot Camp Saloon on the side.”

“This was never going to be my profession, but I worked with some of the most interesting and important people in Milwaukee’s queer history.”

Bartending at Boot Camp was like “starting a whole new school,” Jeremy remembers.

“I learned a whole lot while I was working there. I had this collection of uniforms, and a bit of a uniform fetish, and Si let me wear my uniforms at work. I would show us as a firefighter, police officer, Navy guy, you name it."

"Si was nice enough to let me study art abroad in China for two summers. When I came back, my job was still there waiting for me.”

“People were nice to me. I often worked day shifts, which was when the old-timers and regulars showed up. They would share stories of their lives in old queer Milwaukee, and that was cool to hear. They would tell me about Juneau Park, and how everyone would cruise the park, and hook up behind the statue."

"Growing up, I had no idea cruising existed. Being gay was a secretive thing, not something you would dare to do in a public park. There was this whole way of life that I never knew existed – and it existed long before I was even born.”

“They were mentors to me about queer life, which is not usually something people have someone to teach them. That’s what made this time in my life so memorable. The people, and their stories.”

In spring 2011, Jeremy was in downtown San Francisco when he got a memorable phone call. Boot Camp had burnt down, and it was not coming back, the caller told him.

“I was sad, because everything I knew about Milwaukee queer history came from Boot Camp, and those customers had lost their home. All those different people, and their different experiences, and nowhere to go to tell them anymore.”

Finding his muse

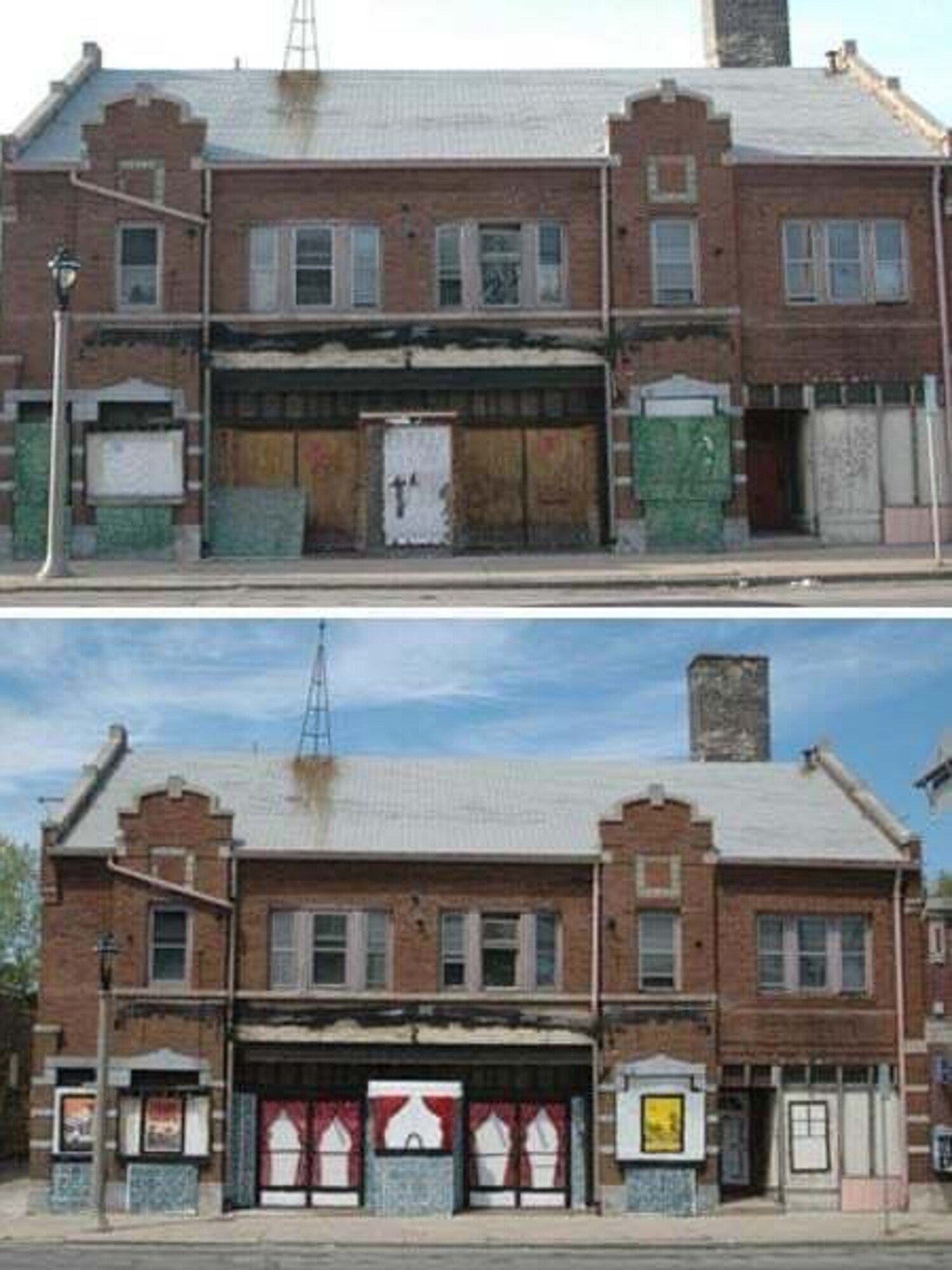

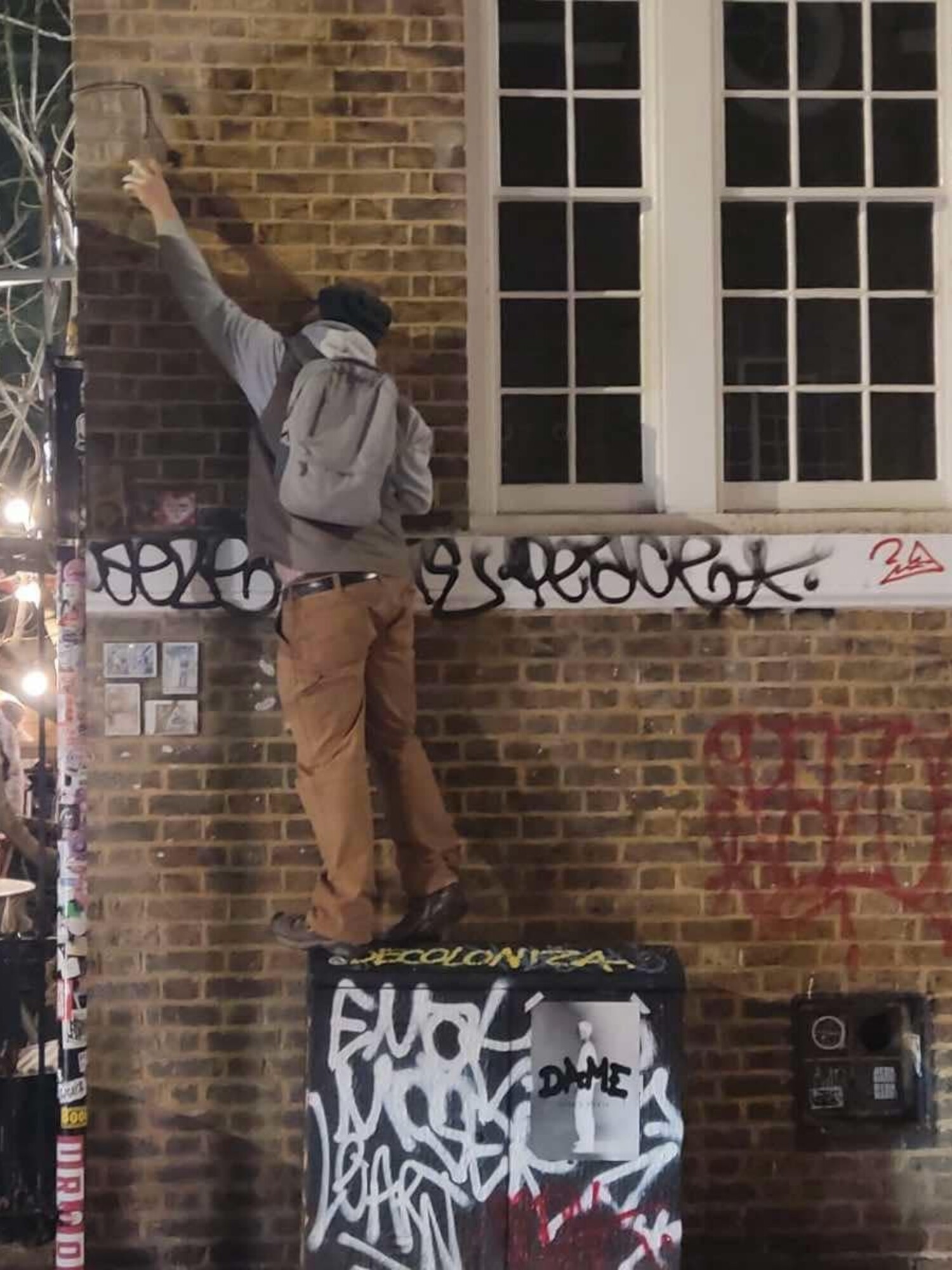

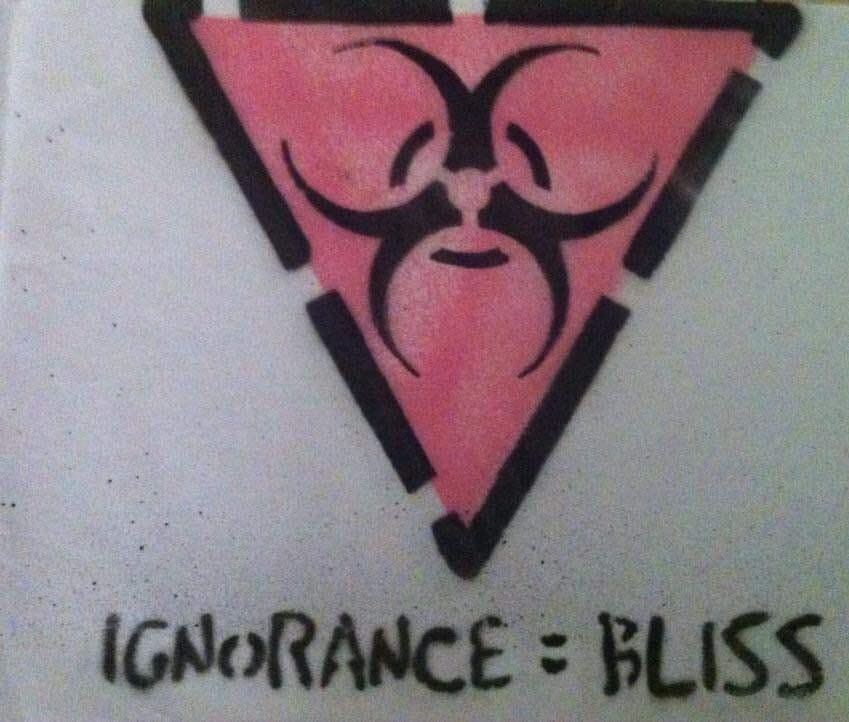

Jeremy became fascinated with artwork that broke the rules, elevated social justice, and gave voices to people who did not have voices. He started doing stencils of doors and windows on boarded-up, abandoned houses, demonstrating the mental health impact these buildings had on people living in the neighborhoods.

“I started documenting my process in photographs,” said Jeremy, “and soon the Wisconsin State Journal was reaching out for an interview."

"When the article came out, I discovered they had interviewed the anti-graffiti people at the Department of Public Works, and they said they only wished I had a different canvas to put my art on. They did not think what I was doing was wrong. They understood that I was trying to make a statement about blight – and they wished there were not boarded-up buildings too.”

“That kind of sparked my creativity,” said Jeremy. “I can put images out into the world about different causes that I feel are important, and people can see them and hear my message. And if I do them well, people will agree with what I am trying to express."

"This is a much quicker way to reach them than through City Hall requests, proposals, meetings, etc. I can cause social change by just doing art.”

“That was fascinating to me.”

“I was doing urban still life, where I’d place an image out into the world that was fixing the urban blight and decay, just by adding some color, or whimsy,” said Jeremy.

“You would have something broken and then you would have something beautiful next to it. I started putting stencils on pay phones in boxes where the phones were no longer there."

"I was trying to highlight things I wanted to change. Maybe we can get rid of some of this decay happening in cities.”

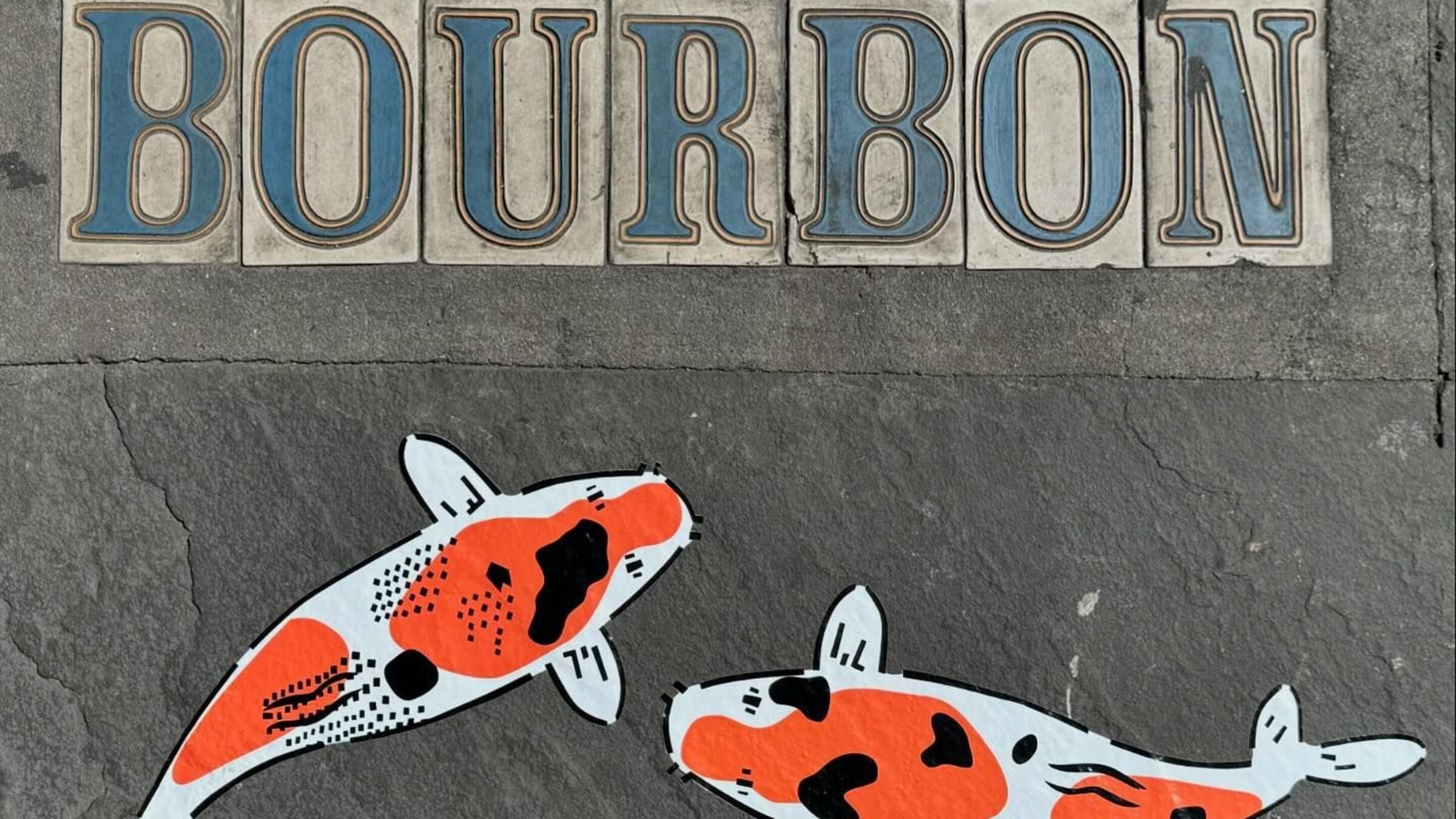

“I started doing koi in 2006 in Milwaukee,” said Jeremy. “When I came back from China, I had to do an art project to earn my credit. I chose koi because I wanted to create a moment of Zen in our chaotic, concrete, urban landscape. And now, they’ve become this iconic image.”

Jeremy joined the arts hoping to find brotherhood. Instead, he found a surprising amount of homophobia.

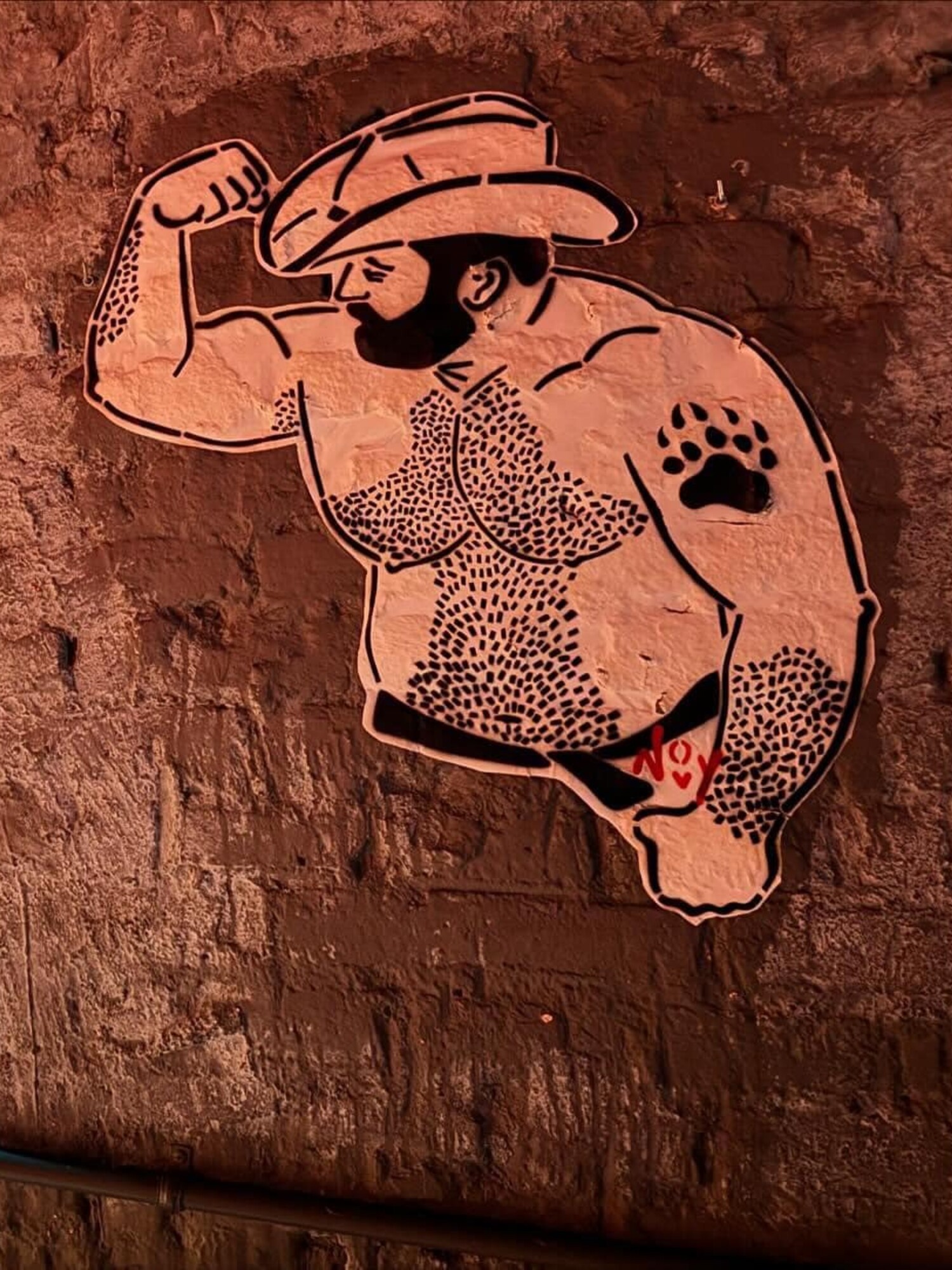

“Graffiti artists were beating up gay graffiti artists. They were tagging queer slurs all over those artists’ graffiti. They used the word ‘gay’ as an insult, not an identity. When I started seeing that stuff, I realized I needed to get more queer images out on the street.”

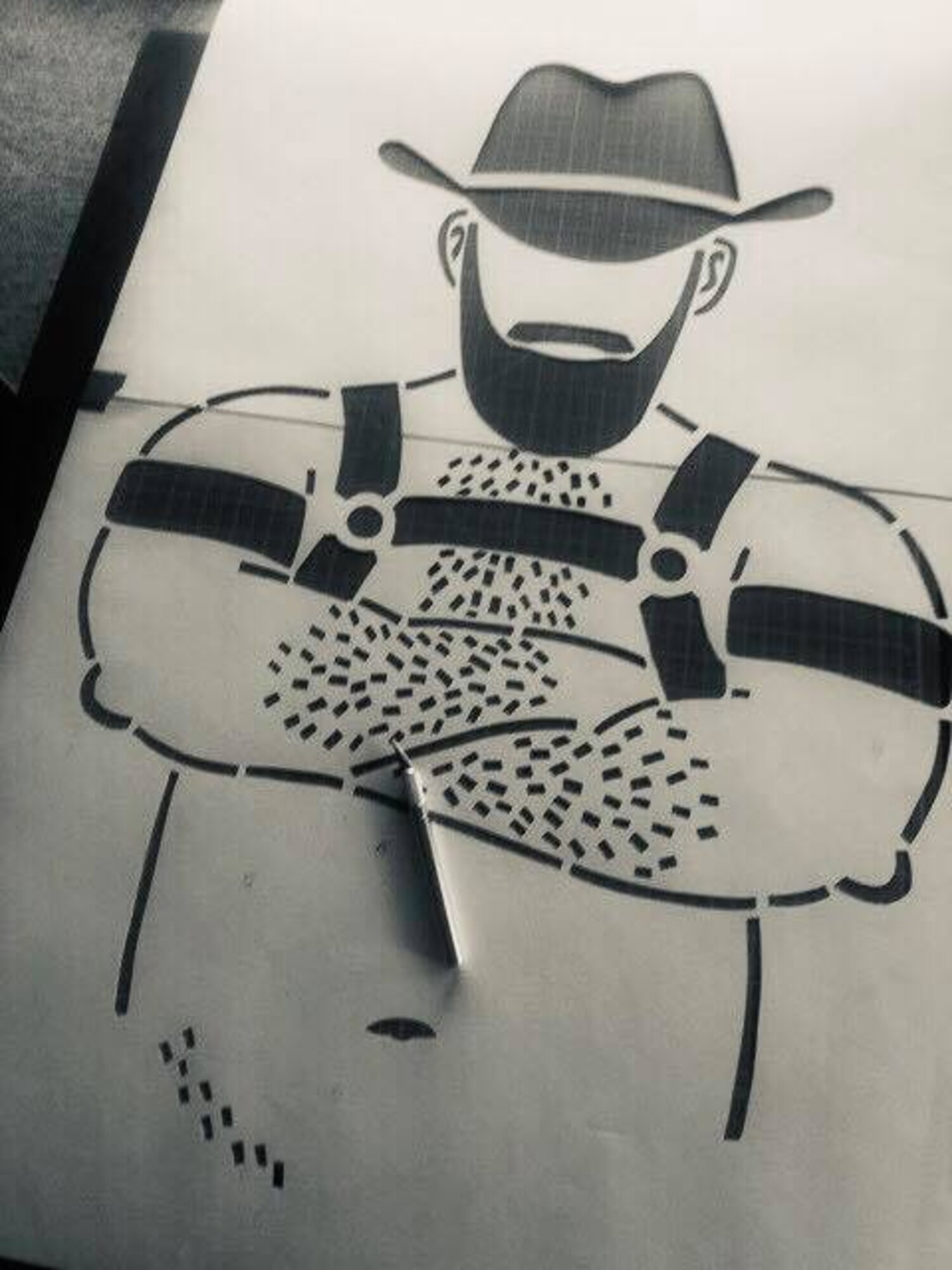

“While I was at Boot Camp, I created a few images that became my trademark. Tom of Finland images, which began as postal stickers. And then I saw the Wigstock documentary, and I thought, ‘this is my kind of happening, where people can be whoever they want to be.'

"So, I did an 8x10 stencil of Lady Bunny. I’d put that out in the streets of Milwaukee, and it would be removed immediately. There could be other graffiti and stickers in the vicinity, but my stencils of anything else would be instantly removed.”

“I was like, wait a second. People love the koi. They find them a beautiful thing, so they ignore them. People of all ages have conversations about how much they enjoy them. It was a common positive experience across the community."

"I thought, this is causing a change. It is making people talk who would not normally talk. It is creating conversation. There is something happening here."

"I need to keep putting out with queer images, to create queer visibility and safe space for the queer community. Just having images on the street is representation."

"It is important for those images to be seen.”