Jamie Nabozny: don't let anyone steal your future

"You need to survive this... and you can survive this."

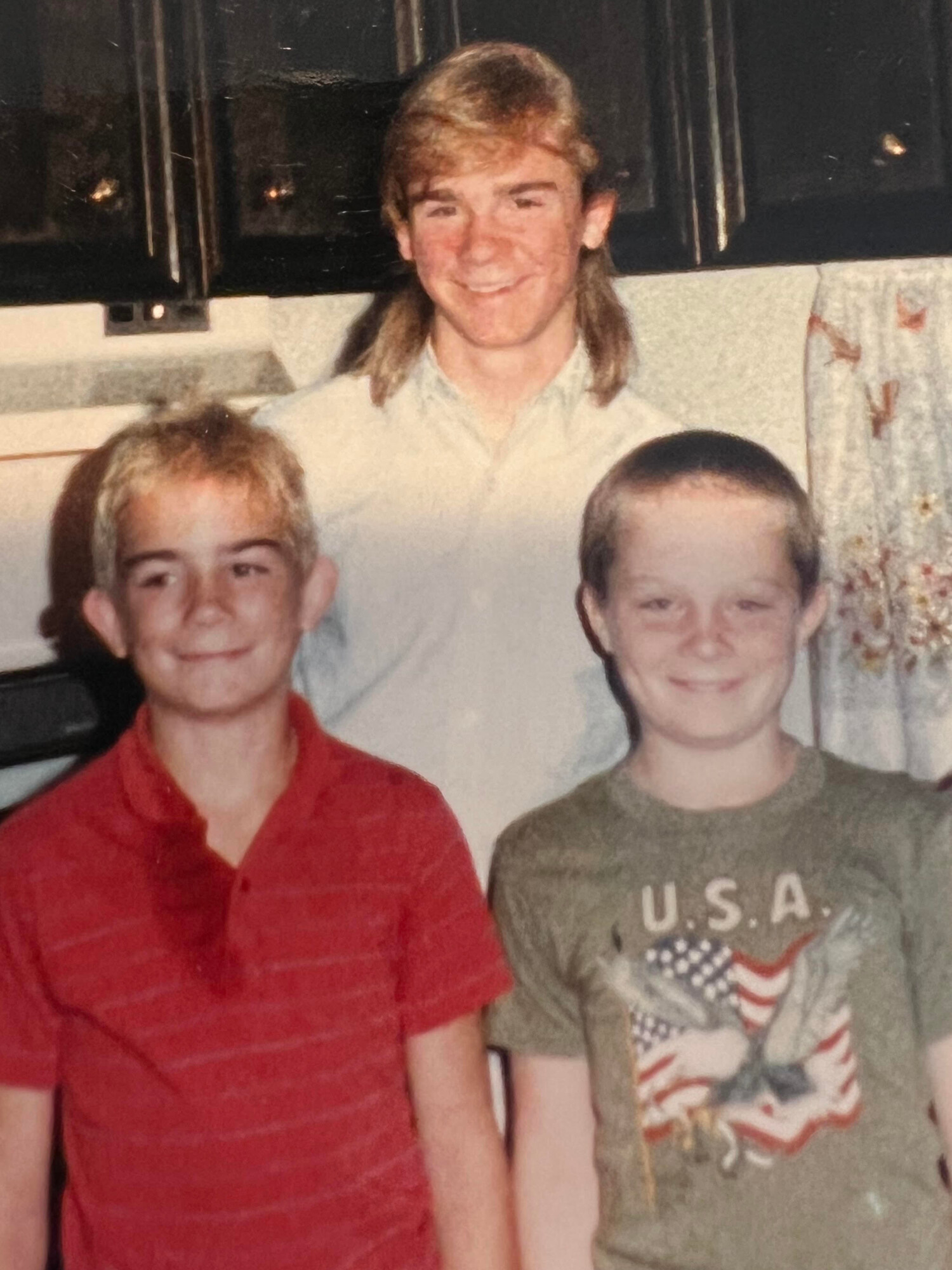

Jamie was born in 1975. He grew near Ashland, Wisconsin, where he lived with his parents and his two younger brothers. He remembers enjoying the great outdoors, camping, and swimming in up north lakes.

“Being poor in northern Wisconsin was really difficult,” remembers Jamie, “and my parents were on and off government assistance. Everything was so unpredictable.”

Seeking better opportunities, Jamie’s father moved the family to Wyoming, where he hoped to find higher-paying work in the Rock Springs mining industry. When that job fell through, he took a construction job in Gillette that only lasted seven months. The family returned to Wisconsin.

“She would say to me, ‘if you’re going to be openly gay, you have to expect this kind of thing,” said Jamie. “And by openly gay, I think I had told her in private that I was gay. She knew, and my guidance counselor knew, but nobody else knew anything. I never told anyone I was gay. I never denied that I was gay either.”

“But in her mind, I deserved this, because I was ‘openly’ gay. She did not like that, she was uncomfortable with it, and she made me know through her actions that she would never support me because of it.”

Victimized and victim-shamed

Realizing his middle school principal was not going to help him, Jamie became increasingly withdrawn. He stopped reporting the incidents as they happened. He would tell his parents, who became more involved, but Jamie became less involved, feeling it would not make a difference.

The violence escalated. Jamie was attacked in science class, where two classmates pushed him to the ground, held him down, and pretended to rape him in front of 20 witnesses. During the attack, the boys accused of Jamie of "enjoying" the sexual assault.

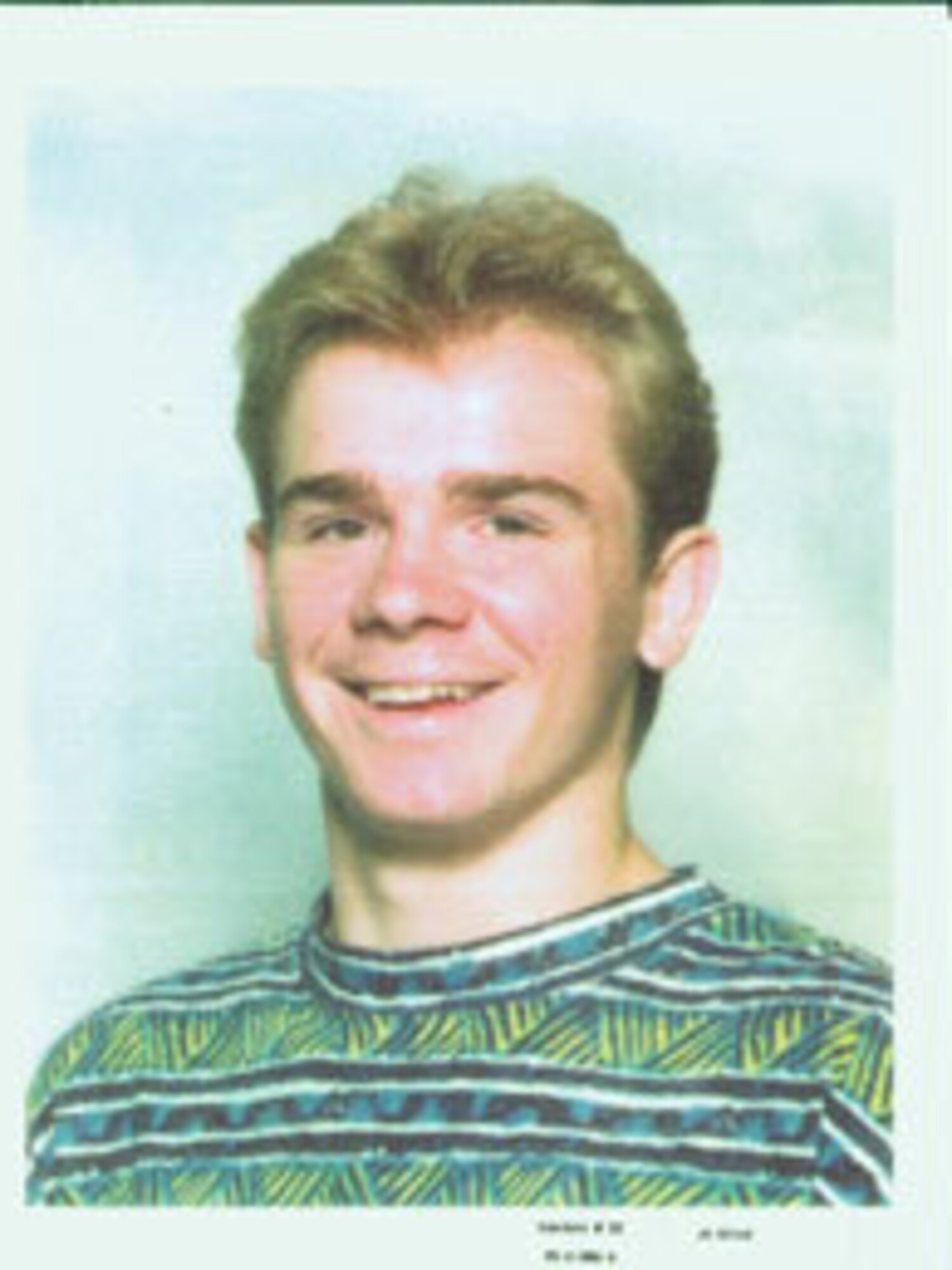

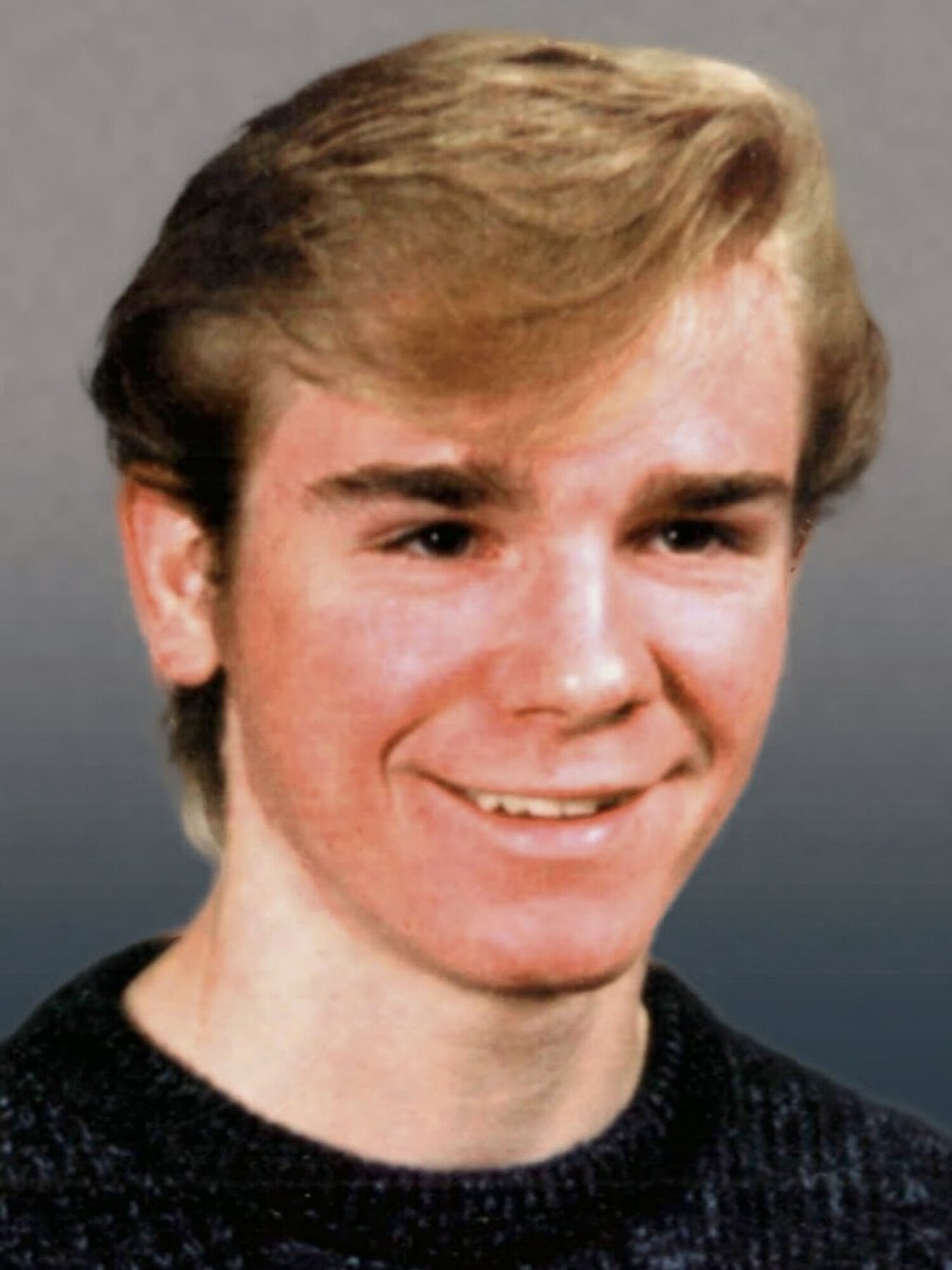

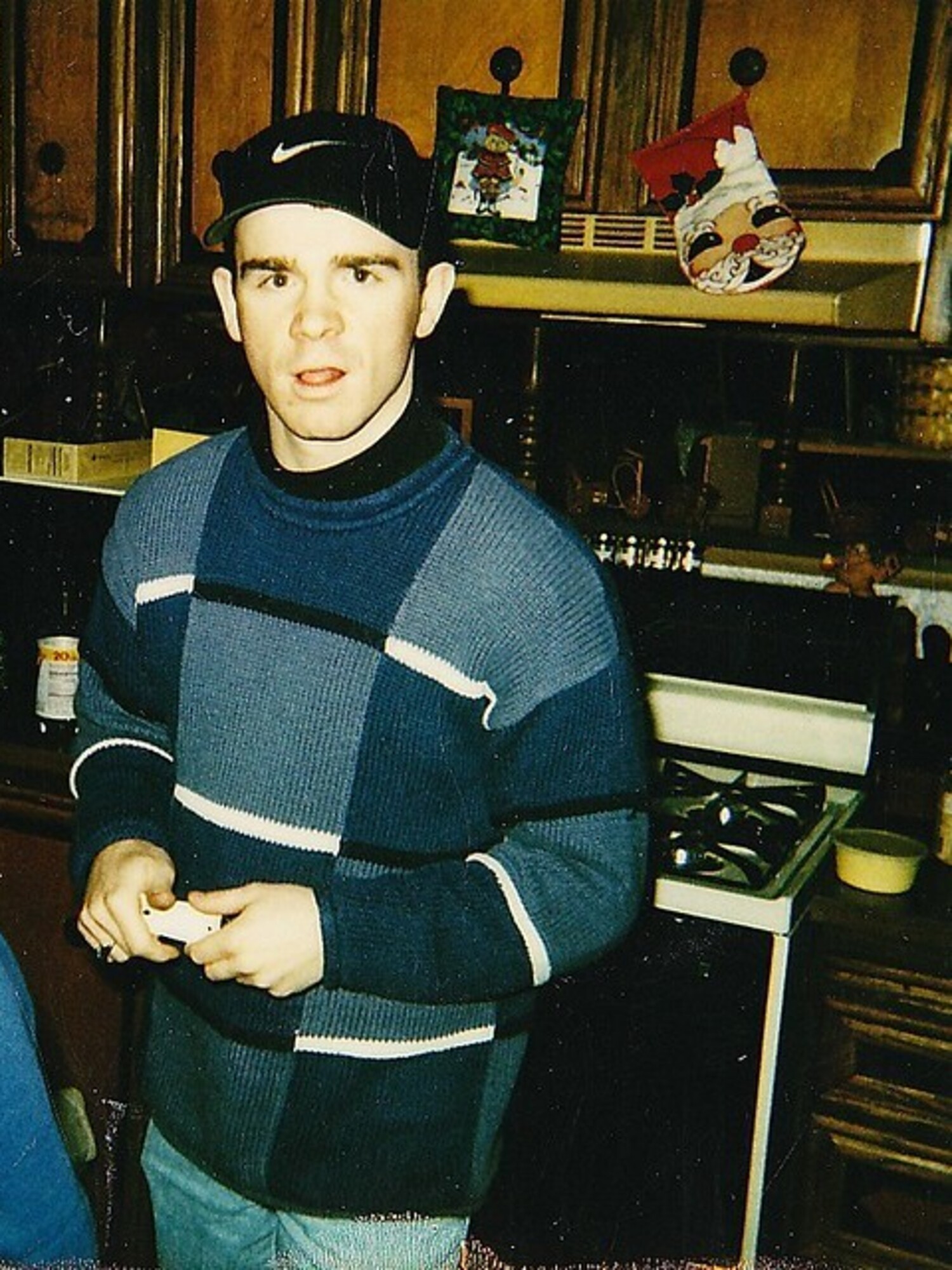

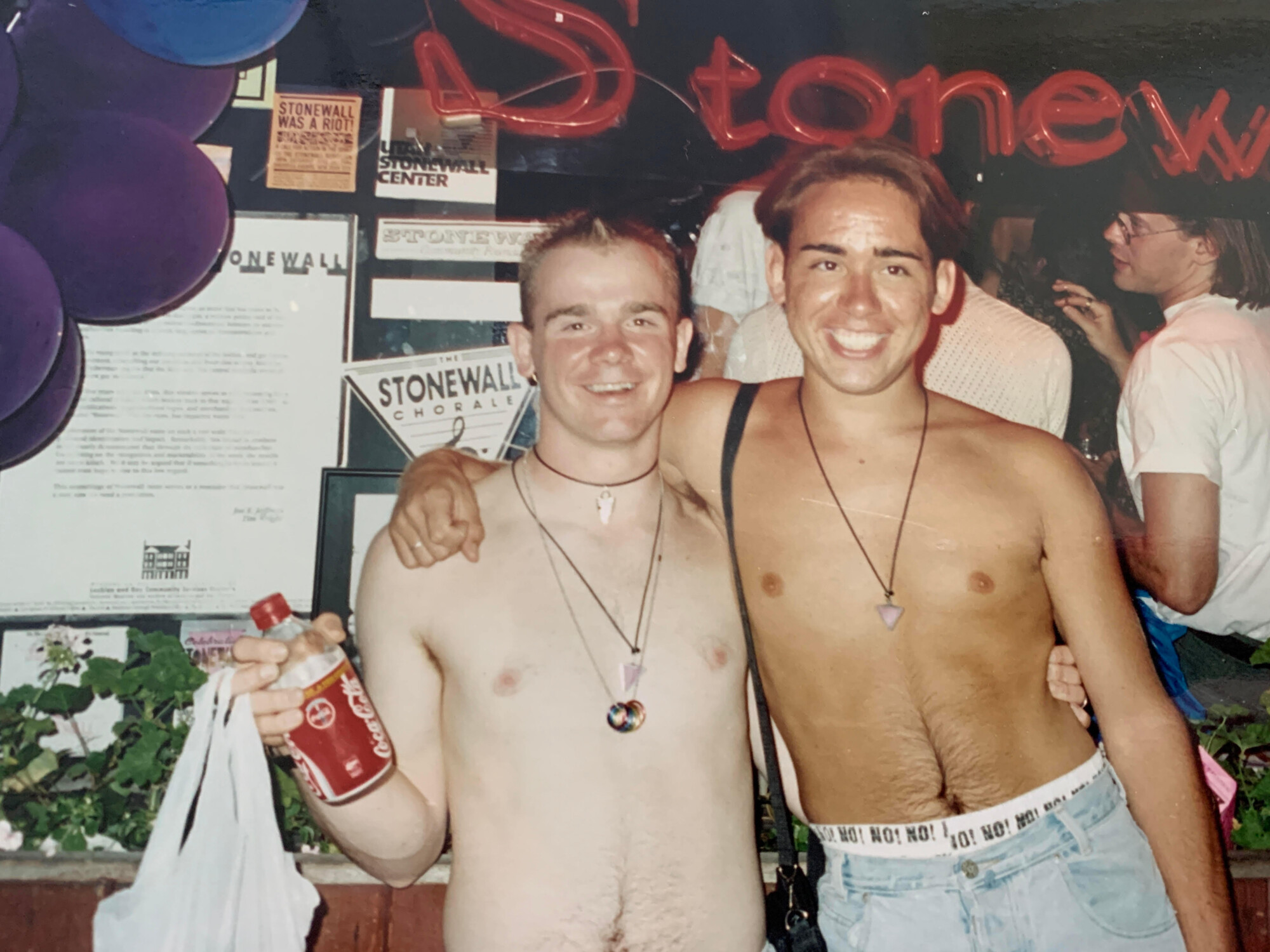

Jamie and friend Jesse

Jamie and friend Jesse

Jamie and friend Jesse

Jamie and friend Jesse

“In my mind, I thought, now they have to do something,” said Jamie. “I have read about situations like this. Now, they must step in. But when I went into her office, upset at having been attacked and violated in front of my entire class, all she said was ‘do you have an appointment? I do not see people without an appointment.’ Not, what happened to you, not why are you so upset, not do you need medical attention? All she said was ‘do you have an appointment’ in the coldest voice imaginable.”

The principal's response was "boys will be boys." She implied that Jamie should expect this kind of treatment "if he was going to be so openly gay." In shock, Jamie left school for the day. The next day, he was sent to a counselor to explain his early exit -- with no regard for the violence he'd suffered at all. No action was taken against his bullies.

As eighth grade continued, the harassment was so bad that a district attorney advised Jamie to take time off from school. When he went back, the harassment accelerated without any intervention from Principal Podlesny.

The situation – and lack of any care for his trauma – drove Jamie to a suicide attempt.

“I just felt like nothing was ever going to change. No matter what happened, no matter what was said or done to me, no matter how far it went. They were not going to stop it. They were not going to help me. They did not care if I lived or died.”

“The principal was a horrible human being. She had issues with Native American students, the only diversity Ashland had at the time, and she treated them horribly. When the school district inherited funding from a local man to build a Native American cultural center at the school, the principal rejected it because it would not benefit all students. She had very conservative beliefs – straight out of the 1940s – except if it were the 1940s, a woman would not have been principal.”

Things get worse

When Jamie got to high school, he hoped – but was not super optimistic – that things would be different. It was a different school, with a different principal, and a different assistant principal. He'd finished eighth grade in a Catholic school, which provided a brief reprieve from the violence.

Unfortunately, none of that mattered.

“The assistant principal was in charge of discipline, but he seemed to want to protect the kids harassing me,” said Jamie. “He did everything he could to blame me for what was happening repeatedly. Homophobia played a part in that. I also learned that he was a troubled kid, who was always in trouble himself, when he was in school. He was always standing up for these kids who were hurting other people. That is just the kind of person he was.”

Appealing to the principal made no difference. Principal Davis believed his assistant principal was doing his job, so he did not see any need to intervene. He was told there were not any issues, and everything was fine, so he never followed up on anything escalated to his level. Neither Jamie nor his parents really understood that there was a superintendent nor a school board, so they thought the principal was the last level of recourse available.

“If they weren’t willing to do anything, then there was nothing you could do,” said Jamie.

Meanwhile, Jamie was just trying to survive day to day – while staying true to himself.

In ninth grade, Jamie was pushed into a bathroom urinal, where another student urinated on him. He reported the incident to the principal, who simply sent him home to change clothes. When Jamie's parents pushed back, the principal recommended that he change his school schedule to avoid the bullies. Instead, the school placed Jamie in a special education class with his attackers.

In the middle of ninth grade, Jamie again attempted suicide -- and then ran away from home. He was only 15.

“I knew high school wasn’t going to be any different from middle school,” said Jamie. “It had escalated to a point where I had gotten badly hurt a few times. I felt like I could not do this anymore. I would not survive three more years of this. I would rather be homeless and on my own than dealing with this."

"So, my best friend (since sixth grade) and I decided to run away to the Twin Cities. We had this fantasy that we could build this wonderful perfect life. Almost immediately, I realized survival meant doing things I did not want to do and would not be comfortable with. We were only here a week and a half before I went home.”

Tenth grade was no better. On the school bus, he was called names, hit with steel nuts and bolts, and constantly harassed. One morning, while waiting for the school library to open, he was violently attacked by eight boys, suffered internal bleeding, and required hospitalization. The bullying had reached life-threatening levels.

Assistant Principal Blauert only laughed, and told Jamie he deserved the beating because he was gay.

“The assistant principal would say, ‘well, when you’re hitting on other boys, they’re going to react,” said Jamie. “You can’t expect them to just sit by when you’re touching them, or flirting with them, or hitting on them.’ Whatever the situation was, I had done something to provoke it. It was the worst type of gaslighting. I was somehow instigating my own abuse, and he was not going to do anything about it.”

“I never told any classmates I was gay until 10th grade,” said Jamie. “One of my Spanish classmates was a foreign exchange student, and she came out and asked me. ‘Everyone keeps saying that you are gay, so are you gay?’ And I said yes. She was genuinely nice about it, and that was it.”

The police were no help. When Jamie’s parents reported the abuse, they would be referred to the school to handle their “disciplinary matter” because it happened during the school day, at the school. When Jamie’s parents asked school administrators to step up, they were told it was a criminal matter that had nothing to do with the school, and that they should press charges.

“Legally, I was in the school’s care, and the police made horrible mistakes by not investigating or prosecuting crimes they were well aware of,” said Jamie. “They acknowledged that in the end, and it resulted in a police liaison program being established at the school. They realized they could not ignore what was happening there or dismiss themselves of their responsibility.”

The second time Jamie ran away, he didn't come back.

"My guidance counselor told my parents that the school was unwilling to help me," said Jamie. "So I decided it was time to go."

In eleventh grade, Jamie left Ashland High School forever. He moved to Minneapolis, where he was treated for post-traumatic stress disorder. In search of legal advice, he connected with the Gay and Lesbian Community Action Council (now OutFront Minnesota.)

“The Internet wasn’t really available yet, so I called their hotline,” said Jamie. “And would you believe, the person I spoke with was OutFront’s lawyer, who was working the hotline that day. After hearing my story, she asked to meet with me, and she listened to my entire story. She was the first person who said, what happened to you was not only wrong, but illegal. I was in shock, because I always knew it was wrong, and I had any power to stop it until she said that.”

“That was the beginning of my lawsuit. She connected me with a local lawyer who started my case, but she wanted the entire proceedings to remain private. No press, no press releases, no speaking out. She wanted a quick settlement. I did not feel great about that, because one of my reasons for doing this, was to make things better for others in my situation. I knew I was not the only one, and I knew that others felt alone and lonely.”

When Jamie got to Minneapolis, he got involved with the District 202 youth center, where he met other kids from all over the state who had endured similar abuse. He realized that he wanted to do more and be more in the world. He wanted to help people like himself.

“Eventually, she dropped out of the case, and Lambda Legal stepped in and took over. Things really started moving fast after that.”

Nabozny v. Podlesny was filed against not only the school district, but several of the school officials as individuals. Attorneys argued that Jamie's Fourteenth Amendment rights, as well as his rights under Wisconsin state law, had been openly and repeatedly violated. When harassment was reported by female students, it was handled immediately -- but that same approach was not applied when gay students were harassed.

A historic verdict

When the news broke about the case, the public was very skeptical. At first, they thought the Naboznys were just trying to get money out of the school. By the end of the trial, the conversation had changed, partially due to consistent coverage in the Ashland Daily Press.

“I think people understood, this isn’t just about name-calling,” said Jamie. “My last beating put me in the hospital and required several surgeries to heal. I had been hospitalized two other times and had to visit the emergency room two additional times due to beatings. This was not your typical playground behavior. This was much more extreme. This was life-threatening. And it was well-known to the people in charge, and they chose not to do anything.”

Despite the lawsuit advancing, Jamie and his family still did not feel safe. His parents received death threats. Their house was shot up before the trial, and they came home to find bullet holes throughout the house. They found dead animals in their mailbox. But, the trial, and coverage of the trial shifted the narrative.

“The trial happened the week of Thanksgiving, and I did not want to go back for the Christmas holiday,” said Jamie. “I decided to go after all. I was at a Citgo gas station when an older lady approached me and asked if I was Jamie Nabozny. I was immediately on edge, thinking, oh here we go. This is why I did not want to come back here.”

“But all she said, ‘I just wanted to thank you. This school is going to be a better place because of you holding them accountable.’”

“And then we went Christmas shopping at Walmart, and people we did not know were coming up to us thanking us and apologizing for all that we had been through. And there were overwhelmingly positive letters to the editor, applauding us for speaking up, and calling for the school leaders to explain themselves. Only one letter was vaguely negative, because the writer wanted to know where the money would come from, outside of bankrupting the school.”

The lawsuit was off to a confusing start. The attorneys were not sure that it was a winnable case, because there was no legal precedent, and the climate was very conservative.

The District Court decided in favor of the school district. Jamie was essentially told that he had no legal grounds to sue, as there was no legal right to be safe in school. The district judge also stated that a school could not be held liable for the actions of students against other students.

Undaunted, Jamie took the case to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit. However, there was no guarantee the case would go to trial. And, if it did go to trial, the same judge who threw it out would not be cooperative in hearing it again. The system would make it difficult for Jamie to win.

“That’s one of the reasons we chose a jury trial, instead of a judge trial,” said Jamie. “We already knew where the judge stood. They said, we cannot win this, and we need to know you are okay with that, but we are also going to do this big media blitz. We want to get your story out there. We want to use your story to educate others. And I felt good about that, knowing how far and wide this problem really was.”

Lambda Legal was getting calls from all over the country from kids and parents coping with homophobic bullying, harassment, and violence. They brought in Skadden, a high-profile Chicago law firm, as a partner for the trial. Jamie’s new attorney was an openly gay, HIV positive partner of the firm, who chose this as his legacy case. Skadden now has an annual symposium in his honor to focus on LGBTQ legal issues.

“The jury selection process was fascinating,” said Jamie. “The trial was the week of Thanksgiving, and this was northwestern Wisconsin. Most of the men would rather be hunting, and eager to come to a verdict so they could get back to hunting season. Most of the jury members were women, and all of them were moms. The head lawyer said, ‘we want to make sure they see you as someone’s kid, so they think about this happening to one of their kids.’

Jamie still cannot believe the Ashland school district’s testimony.

“The principals got up there and lied,” said Jamie. “It is the only way to describe what they did. But then, other witnesses testified the opposite of how we expected. The school receptionist said, yes, she knew my parents because they were in the office a lot. One of the kids’ mothers, who was supposed to be the witness for the school, got on the stand and said, yes, my son did these things, and the school did absolutely nothing about it. Her son was disciplined for beating up other kids, but never when he beat me up. We never expected her testimony to help us, but it did.”

On July 31, 1996, Judge Jesse Eschbach wrote a pointed response.

"The question is not whether (the defendants) are required to treat every harassment complaint the same way: as we have noted, they are not. The question is whether they are required to give male and female students equivalent levels of protection. They are, and the law clearly said so, prior to Nabozny's years in middle school."

The court unanimously agreed that school officials had violated Jamie's constitutional rights.

"We conclude...that the District and defendants Podlesny, Davis, and Blauert violated Nabozny's Fourteenth Amendment right to equal protection by discriminating against him based on his gender or sexual orientation. Further, the law establishing the defendant's liability was sufficiently clear to inform the defendants that their conduct was unconstitutional. Nabozny's equal protection claims are reinstated in toto."

The entire court record can be viewed online.

“My biggest memory was the verdict taking an hour and a half, which is unheard of,” said Jamie. “My lawyers said that is either good or bad. We were prepared for the worst at that point. We had no idea. We were expecting to lose. The head lawyer said, I need you to not respond when they read the verdict, do not cry, do not scream, do not do anything. Any reaction could affect the damages phase. You need to stay neutral.’"

“When the judge read the verdict, the person who reacted the most was the head lawyer! He had tears coming down his face because he was so happy. We left there, hugging, and crying, despite trying to stay quiet and emotionless.”

In November 1996, the jury found school officials liable for failing to stop the violence. Before the jury could determine the damages, school officials requested to settle.

“We were supposed to return the next day for the damages phase,” said Jamie. “But that night, they tried to negotiate a settlement that took five hours to finalize. I went to bed that night in a state of disbelief. I do not know how else to explain it. When I was in the shower the next morning, I heard on the radio that a settlement had been reached. It was the number one news story of the morning. I broke down crying because it did not seem real until that exact moment.”

“When I heard it on the radio, I was like, oh my God, it’s over, I won.”

The case settled for $962,000 in damages. A year later, the Department of Education clarified that Title IX requires schools to provide a safe environment for all students -- including gay and lesbian students. The case launched a national groundswell in awareness and advocacy for the learning experiences of LGBTQ youth.

Aftershocks

Oddly, the Ashland School District did not really face any sanctions, penalties, or consequences, outside the court proceedings. The civil case --- which did not invoke any civil rights protections -- did not result in any discipline for any of the school administrators, but within 1-2 years, all three of them were gone.

“I think there was a quiet, but deliberate effort to get rid of them,” said Jamie. “That has never been confirmed officially anywhere, but it is strange that all of them were gone so quickly after the trial. Mary Podlesny was rumored to have a nervous breakdown. She went on leave and never came back to the school district. She wound up being a very unpopular professor at Northland College. Principal Davis retired and assistant principal Blauert relocated to Superior until he retired in 2012. It was a complete housecleaning, whether anyone will ever admit it.”

"Principal Davis was the only person I ever received an apology from,' said Jamie. "He felt he could and should have done more and he felt terrible about that."

After the trial, Jamie reconnected with some of his bullies – sometimes in surprising and unexpected places.

“I ended up working with one of them at Wells Fargo,” said Jamie. “I was managing people coming into the company from outside of banking and developing them into becoming bankers and managers for our branches. He was one of the branch managers and we wound up at happy hour together. He took me aside, and said, ‘you know, I feel bad about everything I did, and I wanted you to know that. Having my own children makes me see the world very differently.’ All I could say to him was ‘thank you, I appreciate that.’”

“Another one lives in the Twin Cities, and he sent me a Facebook message when his own son was being harassed,” said Jamie. “He said it made him realize the harm he had caused. He was not someone who physically hurt me, but he did call me a lot of names. But he sent me a very genuine apology, explaining that he now understands what my family and I went through.”

“And here’s the weirdest story of all: I was getting a birthday card for a friend at a gay bookstore in Minneapolis, back when there were gay bookstores in Minneapolis,” said Jamie. “I noticed someone was in the backroom where the adult movies were located, but they kept ducking down to avoid me. But they could not get around me without being seen, because the exit was behind me."

"So, eventually, I went around the corner to see him, and I knew exactly who he was. He came up to me terrified and said, ‘I’m so sorry, please don’t tell anyone, it will ruin my life.’ And I am just standing there, trying to figure out what to even say or do in this situation, and finally I said, ‘you must live with the fact that you are who you are, and you did what you did for the rest of your life. There is nothing I can do to make that worse.’

“He left quickly. I had a whole lot to think about after that moment. Do I say something? Do I out him? Sadly, he is now a minister, married with three children, and I am quite sure he is closeted and probably cheating on his wife, while preaching that being gay is a sin. I actually feel very sorry for him."

“And I know others like him. Two of the ten bullies named in my lawsuit came out, and I know two others who are closeted. Four of these ten boys were so afraid of people finding out about them, that they took it out on me. One came out to his sister while in prison, and she reached out to me thinking I should know.”

Jamie today

Jamie today

Jamie and his husband

Jamie and his husband

Life goes on

After the case ended in 1996, Jamie agreed to support Lambda Legal with fundraising and speaking projects. He traveled coast to coast to support the organization. He was happy to do it, never realizing the emotional impact of telling his story repeatedly.

“I didn’t know how it would affect me from day to day,” said Jamie. “There were days I did not want to get out of bed. I had not dealt with what had happened to me. My PTSD was hammering me with a vengeance, and I had a really challenging time being in crowded spaces."

"After about nine months, I had to stop with the speaking tour. I just could not do it anymore. I quit talking about it with friends and family. And that lasted for over 12 years.”

In 2009, the Southern Poverty Law Center approached Jamie about making a movie about his life. Initially, he declined the offer.

He was living in Minot, North Dakota, with a boyfriend of 12-18 months, and overseeing thirteen branches in the western half of the state. When he got off the phone, his boyfriend asked what the caller wanted – and Jamie realized he did not even know how to explain the request, as he had never even told his boyfriend about his experiences. Halfway through that conversation, his boyfriend stopped him and said, ‘I already know all of that, because I Googled you when we started dating.’

As someone who endured bullying himself, he encouraged Jamie to pursue the documentary.

With the support of his loved ones, Jamie agreed to do the film. The project, Bullied, was narrated by actor Jane Lynch. The film became part of the Law Center’s Teaching Tolerance series.

“I didn’t realize how big the Southern Poverty Law Center was, or how big of an impact the film would have,” said Jamie. “At that point, they put out a film every few years, produced 10-15,000 copies, and shared them with liberal schools around the country. My film extended their reach, because it was a relevant topic for all schools and all students. And it got me back into the public speaking space, because people wanted to meet me and hear my story again.”

Jamie agreed to go on a speaking circuit for a year but wound up doing it for four years.

There were two attempts to produce a feature-length film on Jamie’s life story. The first attempt was sponsored by Bette Midler’s production company, which shocked Jamie as a life-long Bette Midler fan. While the films never came to happen, he is still hopeful that his story will be revisited someday.

“I’d love to see a streaming channel do an 8-9 episode series, because I think that would be a more powerful way of telling my story,” said Jamie. “There are a lot of kids out there who need help, and hearing my story might give them the inspiration they need. “

Jamie and his husband were married on top of a Duluth, Minnesota ski hill. They've been together for 17 years. In 2014, they decided to start a family. At the end of 2016, they became the parents of four children. Today, the family lives in the Twin Cities, where Jamie works as an insurance agent.

Jamie and family

Jamie and family

Jamie and family

Jamie and family

Closing thoughts

Reflecting on the recent Title IX lawsuits in Wisconsin, Jamie recognizes we still have a long way to go before all students feel safe at school.

“I do believe it’s gotten better in some places, and for some kids,” said Jamie. “I think the biggest problem we are still facing today is that kids who are not gender conforming face a lot of abuse. That was true when I was young, and it is even more true today."

"Why? Because those kids are not staying in the closet. They are no longer afraid. They are coming out and finding their place in the world. They are not biding their time or laying low so they can graduate and leave their hometowns. Kids are coming out younger and younger, and they are expressing and defining themselves more fluently, even if they do not have full family support.”

“Nowadays, boys can come out, and they can be on the school football team, and everyone’s celebrating them, because they’re acting exactly how a boy is expected to act,” said Jamie. “But that same kid would get a quite different response on the swim team or gymnastics team. The reason is that sexism is still stronger than homophobia in schools. Sexism, at its heart, still rules how we respond to each other, and it starts in how we are taught in schools.”

“My words of encouragement are the same today that they were in the ‘90s,” said Jamie. “The first one is that you are not alone. There are literally millions of kids out there being bullied and feeling alone, just like you. The second thing is that what is happening is wrong – and you have a right to be protected in school. Ask for help, and do not stop asking until someone listens to you."

"Everyone has a boss. If the teacher isn't helping you, you report it to the principal. If the principal refuses to help, then go to the superintendent."

"And my last point, you need to stick around to see how amazing your life will be. I wish I could go back and tell my 14, 15, 16-year-old self what my life is like now and give him the strength and hope he needed to see what the future brings.”

"You never know how amazing your future could be."

Jamie and his family

Jamie and his family

recent blog posts

December 17, 2025 | Michail Takach

December 16, 2025 | Michail Takach

December 01, 2025 | Dan Fons

The concept for this web site was envisioned by Don Schwamb in 2003, and over the next 15 years, he was the sole researcher, programmer and primary contributor, bearing all costs for hosting the web site personally.