George Poage: the thrill of victory, the agony of being seen

It’s an understatement to say George Coleman Poage (1880–1962) achieved tremendous historic victories throughout his life.

He was the first African-American graduate of La Crosse High School—a school not segregated by race—and graduated second in his class. He was the first African-American member of the University of Wisconsin track team and the Milwaukee Athletic Club. He was the first African-American athlete to win a Big Ten track championship. He was the first African-American member of the UW-Madison Philomathia Society, a fraternal order composed of “seekers of truth and knowledge.”

In 1904, he was the first African American to receive an Olympic medal. He was later elected to the Wisconsin Athletic Hall of Fame.

So, why isn’t his name recognized? Not in Madison, where he reached the heights of his athletic fame? Not in Chicago, where he spent over half his life?

And until recently, not even in La Crosse, where his story began?

From La Crosse to the Louisiana Purchase Exposition

George Poage was born in Hannibal, Missouri on November 6, 1880. His father, James, was born into slavery. His mother Anna had “freedom papers.” The family left this Mississippi River steamboat town for opportunity in La Crosse. James took a job as coachman to Jason Easton, a lumber baron, and the family took up residence in the coach house.

However, James died in 1888, leaving Anna with children to feed.

Rather than being discouraged by this challenge, she leaned into it, and set some remarkable goals for her son, George. She instilled in him gentleman’s standards: Always controlling impulses, managing emotions, and withdrawing from conflict. Black men were widely seen by whites as volatile, unreasonable, and out-of-control, and Anna vowed her son would prove that stereotype wrong.

One day, George’s athletic skills were noticed when he sprinted across a city park, and he was welcomed to join the track team. His spectacular race times drew regional attention from UW coaches and talent scouts, who steered him toward college at UW-Madison.

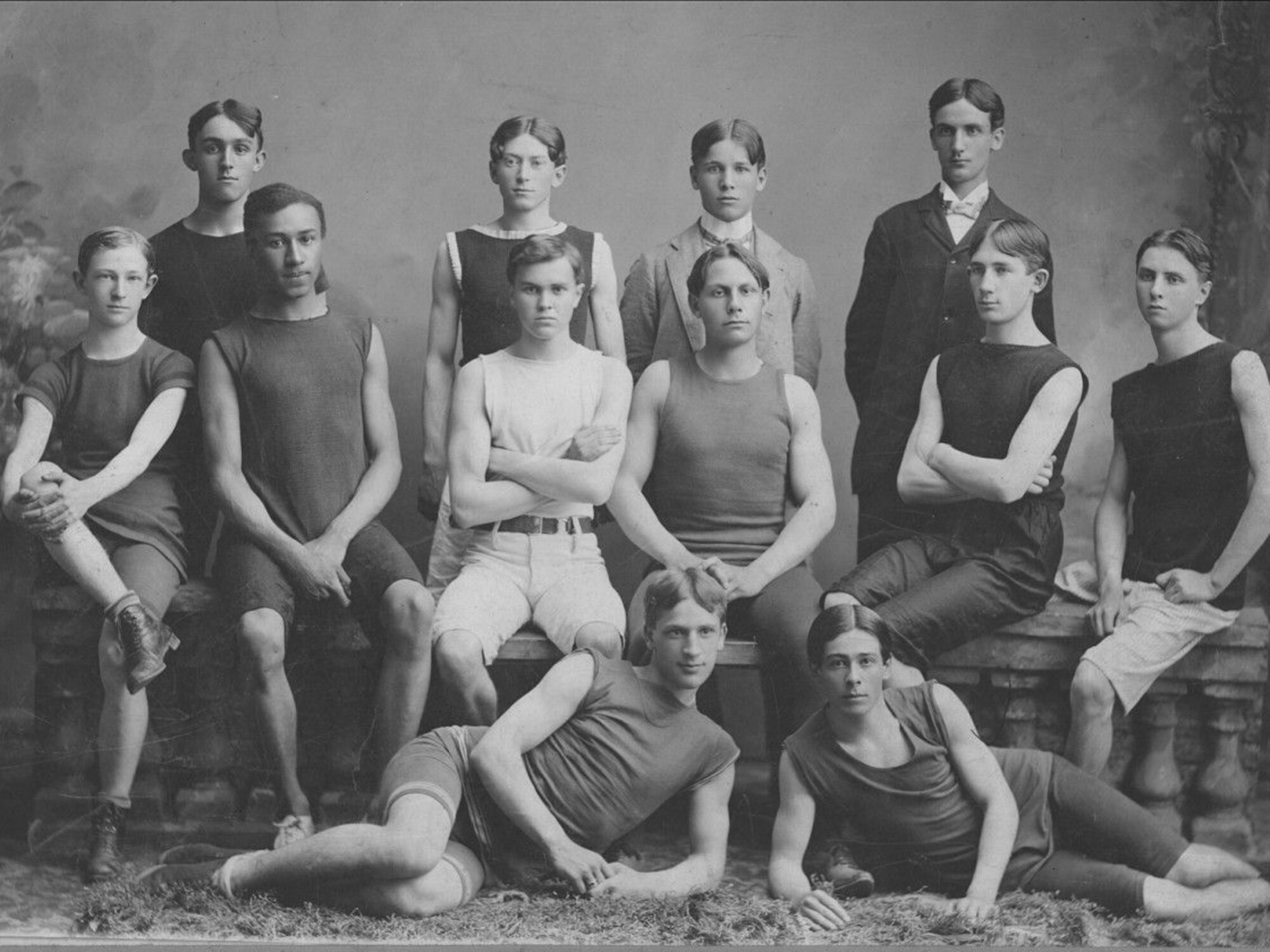

Sports were racially segregated in 1899, but Poage’s advocates couldn’t have cared less. They recognized a winner and sought to build a winning team. UW-Madison was an economic challenge for the Poages, but a deathbed dowry from Jason Easton put college within reach.

Before leaving La Crosse, Poage was involved in a peculiar situation that has raised the eyebrows of several historians. On August 18, 1899, he was involved in a public fight with another Black man. Three days later, a warrant was issued, Poage was arrested, and he pleaded not guilty. The charges were dismissed, and the details of the case were never reported. What’s unusual, culturally, and historically, is that Poage’s warrant was requested by another Black citizen. While Poage’s story was that his temper had gotten the best of him, he was never known to be temperamental, violent, or dangerous—in fact, he had never been known to express anger of any kind.

Whatever happened on August 18, 1899, was deeply personal, highly emotional, and—most importantly—outside the limits of the local community’s capabilities. Someone wanted Poage out of La Crosse, for reasons we will never know.

It was the first hint of a life unseen and unknown by public eyes. And Poage certainly knew about the “Race Problem,” and his high school commencement speech focused entirely upon it. He was leaving the big city of La Crosse (population 29,000) for the small town of Madison (19,000). He knew he’d need to be on his best behavior.

High standards were set for Poage before he even got there. The university’s athletic leaders, coaches, newspaper, alumni, and marketers saw him as magical. He spent the next five years sprinting to outrun ever-increasing academic and athletic expectations, increasingly unsure if meeting them was even humanly possible.

He was bombarded with reminders that he was a Black man in spaces meant for white people. The news media was cruel under the guise of complimentary, calling Poage “colored lad,” “colored quarter miler,” “crack colored sprinter,” “colored wonder,” “dusky star,” and shockingly, “the Negro player.” He was no longer an individual person—he was now just the “colored Badger.”

While his grades slipped year over year, Poage graduated in June 1903 with a full year of college sports eligibility remaining. The university wasn’t going to let him go easily.

“It will seriously cripple Wisconsin on the track were George Poage to leave,” wrote the Janesville Daily Gazette on June 25, 1903. University management convinced him to stay on campus, taking just enough credits to meet athletic requirements. When the coach was away, Poage was asked to manage the team in his absence. He also took a job at the football training quarters. The scheme was widely recognized for what it was: A clever way to pay athletes to perform after graduation.

During this final year, the Milwaukee Athletic Club approached Poage with a membership offer and an invitation to run for the club. The Third Olympiad was coming to St. Louis, to coincide with the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, and the Club was assembling the midwest’s greatest champions to compete. While his membership was delayed until his studies ended, Poage ran for MAC at Milwaukee competitions throughout 1903. He was repeatedly reminded that he was an exception. His athletic reputation—and nothing more—made him the state’s most famous African American.

And that wasn’t going to last forever.

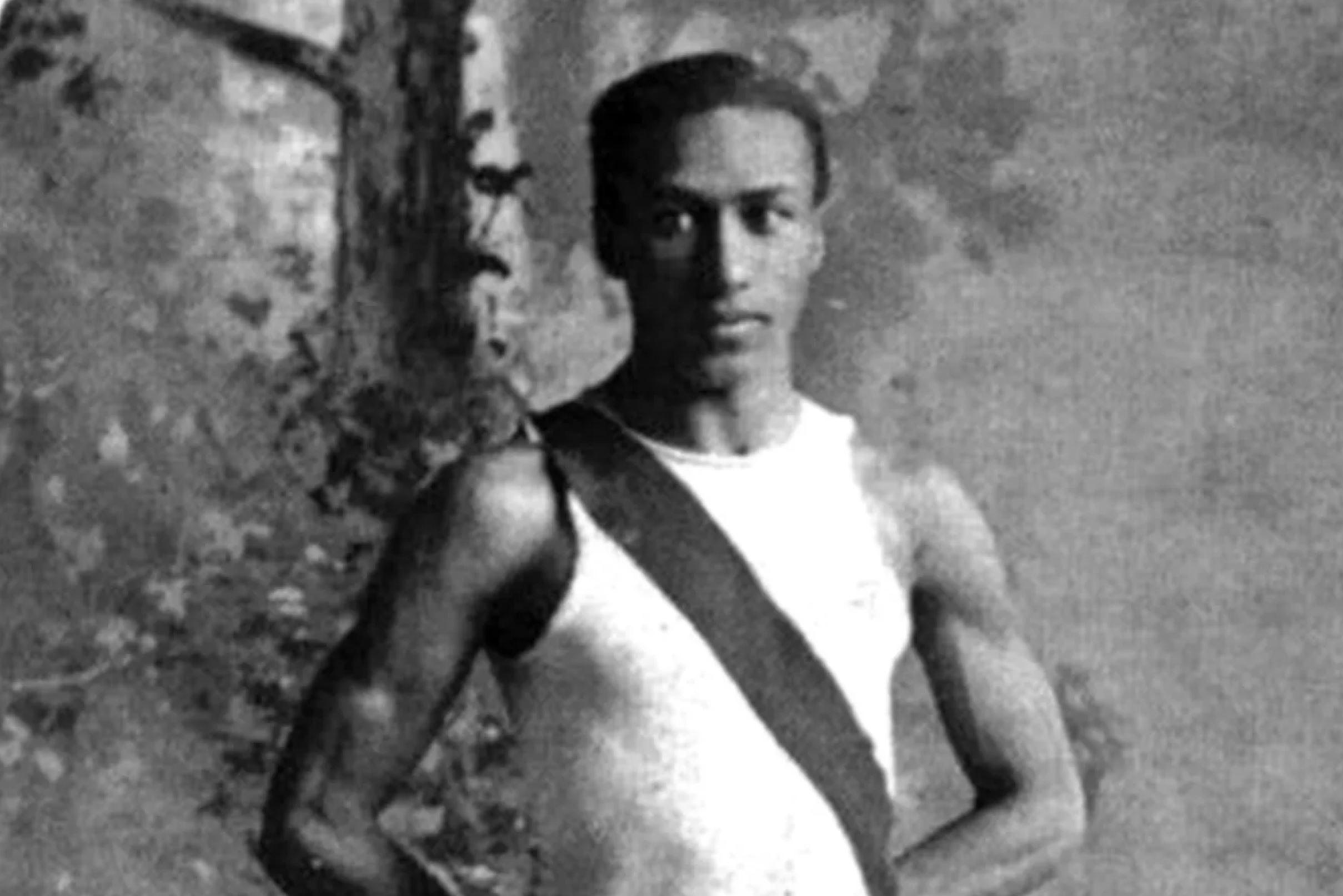

George Poage at the Olympiad

George Poage at the Olympiad

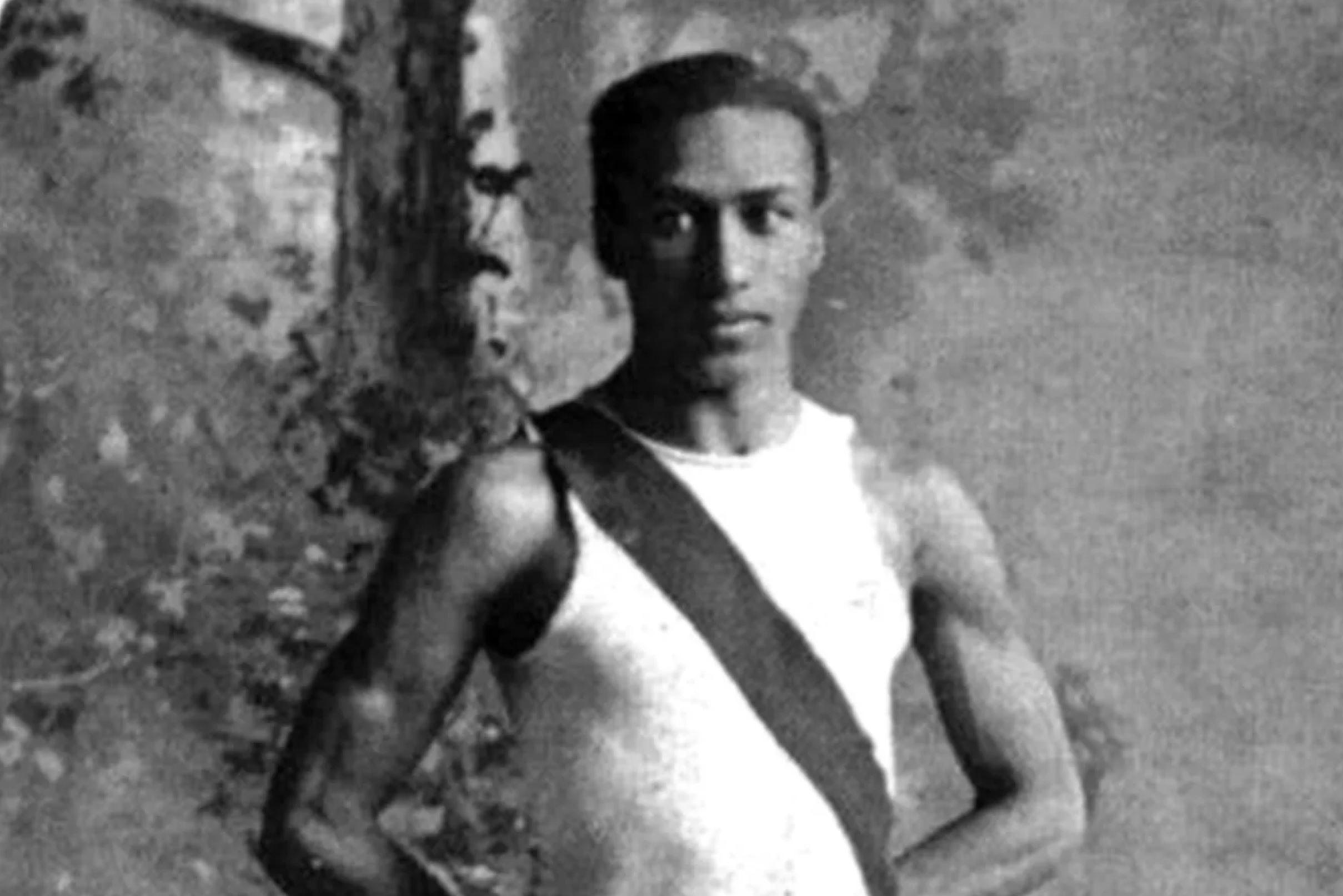

George Poage at the University of Wisconsin-Madison

George Poage at the University of Wisconsin-Madison

Victory & defeat

The 1904 Olympiad and Louisiana Purchase Exposition had to be a surreal experience. It was America’s largest celebration since the Chicago Columbian Exposition, bringing a victorious nation and President Theodore Roosevelt together after the Spanish-American War.

But the events were laced with a toxic spice of “white man’s burden,” including Southern School of History exhibits depicting the “historic benefits” of plantation life, the “natural condition” of the American Negro, and the Civil War as an attack on Southern traditions and customs. During Anthropology Days, organizers forced “uncivilized tribes” (i.e., Patagonians, Filipinos, Inuits, Sioux, and Ainu people) into bizarre competitions to prove their genetic inferiority. Racism was embedded into a national celebration—and people were rightfully offended.

“In no place but America would one have dared to place such events on a program, but in America, everything is permissible,” said Pierre de Coubertin, founder of the International Olympics Committee. Many leaders called for a boycott of the Olympiad and Exposition.

Poage did not listen. Many white newspapers applauded his decision to attend the Games, while equally applauding the segregation of grandstands, bleachers, exhibits, housing, food service, and restrooms.

He was effectively running for free. Any honors won in the Games were seized by the sponsors, not retained by the athletes. There were no monetary rewards. There were no future endorsement deals at the finish line—except maybe sponsorship for the next competition.

On August 31, 1904, he took third place in the 400-meter hurdles, and a bronze medal the next day in the 200-meter hurdles.

After the Games, he chose to stay in St. Louis, where he accepted the role of principal at the brand-new William McKinley High School in South St. Louis. He had never taught before, nor attended a segregated school system, but the School Board sought to leverage his celebrity for gain. Within a year, he was reassigned to teach at Charles Sumner, the city’s premier African-American high school.

His teaching career came to a strange and sudden end in spring 1914. Vicious rumors circulated that Poage and two other unmarried male teachers were secretly meeting in ragtime cafes. School administrators insisted there was no cause for alarm; after all, the teachers were among the best educators in Missouri.

The St. Louis Star and Times reported that the allegations were a “frame up,” but school board members believed the school was harboring a dark secret. No accounting of the teachers’ talents, accolades, or achievements would sway their rage.

Within weeks, a committee of parents, school board members, and civic leaders filed formal complaints against Poage and his colleagues, questioning their moral character and social intentions. Twenty students came forth to prove that the teachers’ “immorality” was common knowledge at Sumner High School. Abruptly, Poage sent a letter of resignation and vanished.

Wrote the St. Louis Argus, “Mr. Poage was one of three teachers brought before the board involving their moral character…it is said the committee made a very strong case. Some of the most damaging testimony was introduced, and a startling condition of affairs was disclosed.”

There was never any accounting of what this “damaging” and “startling” evidence was. Meanwhile, his colleagues—who came from prominent local families—fought the charges, sued for damages, and won both a settlement and their jobs back.

What would Poage fear so much that he would abandon his 10-year teaching position without a fight? Was he devastated that his beloved students turned on him? Was he lonely in St. Louis after his family moved on to Denver? Was he truly that concerned, as he later told historians, that his health was in danger? Was he just tired of living in constant fear of being found out for something?

The decision changed the course of his life.

Disappear here

For a while, Poage had a limitless future ahead of him. Now, he had nothing to show for his 37 years, and less to look forward to. So, he tried to lose himself in a new city where nobody knew his name.

Draft records indicate he was living in Chicago between 1914 and 1918. Within the Bronzeville neighborhood, he was near South State Street, Stateway Field, and the rowdy cabaret district. The “Black Belt”—a tenderloin district with nightlife destinations Cabin Inn, Pleasure Inn, Club De Lisa and more—attracted crossover crowds from as far away as North Chicago.

He was close friends with Hugh Buchanan, one of Chicago’s greatest musical talents—and another unmarried man who lived with his mother. Both were members of the Chicago Athletic Club, a popular gathering (and cruising) space for gay men. He also associated with Lillian Davenport, a comedian, musician, producer, and La Crosse graduate.

There was virtually no risk of scandal following him to Chicago. But he never again pursued any role in education, even though he was certainly qualified to do so.

By May 1924, Poage was working as a cook at the Horn & Hardart Automat (116 N. Dearborn). When he learned the Chicago Post Office was hiring temporary clerks, he applied and was hired immediately. By December, he was a full-time employee; five years later, he’d nearly doubled his salary. In 1930, he was transferred to Sears headquarters. He made enough money to buy a new Art Deco apartment.

Poage died of pneumonia on April 11, 1962, and was buried in an unmarked grave in Lincoln Cemetery in Blue Island, Illinois. Very little is known about the last three decades of his life.

Who was George Poage—really?

By 1984, when Dr. Bruce Mouser and Edwin Hill presented at the North American Society of Sports History’s annual conference, Poage was an unknown, despite being admitted to the Wisconsin Athletic Hall of Fame in 1958.

He could have been an athlete, a coach, a trainer, a historian, an educator, an entertainer, even an author. Instead, he was forgotten. After being pursued by the greatest universities and athletic clubs of the era, and after reaching the great heights of the 1904 Olympiad, how can one really accept a lifetime sentence in a Sears stockroom?

In August 2016, Reverend Lawrence Jenkins casually leaned over to Dr. Mouser and said, “Of course, you know my great-uncle was gay.”

“Our George Coleman Poage had to hide his intellect and his academic accomplishments as much as he had to hide his sexual orientation. The racist society in which he lived had no room for either. The miracle of his survival under those conditions is what stands out to me,” said Reverend Jenkins.

George Poage’s legacy is finally being seen. In 2016, the City of La Crosse rededicated a local park in Poage’s honor. Recently, he was honored in the PBS Wisconsin documentary, “Wisconsin Pride.”

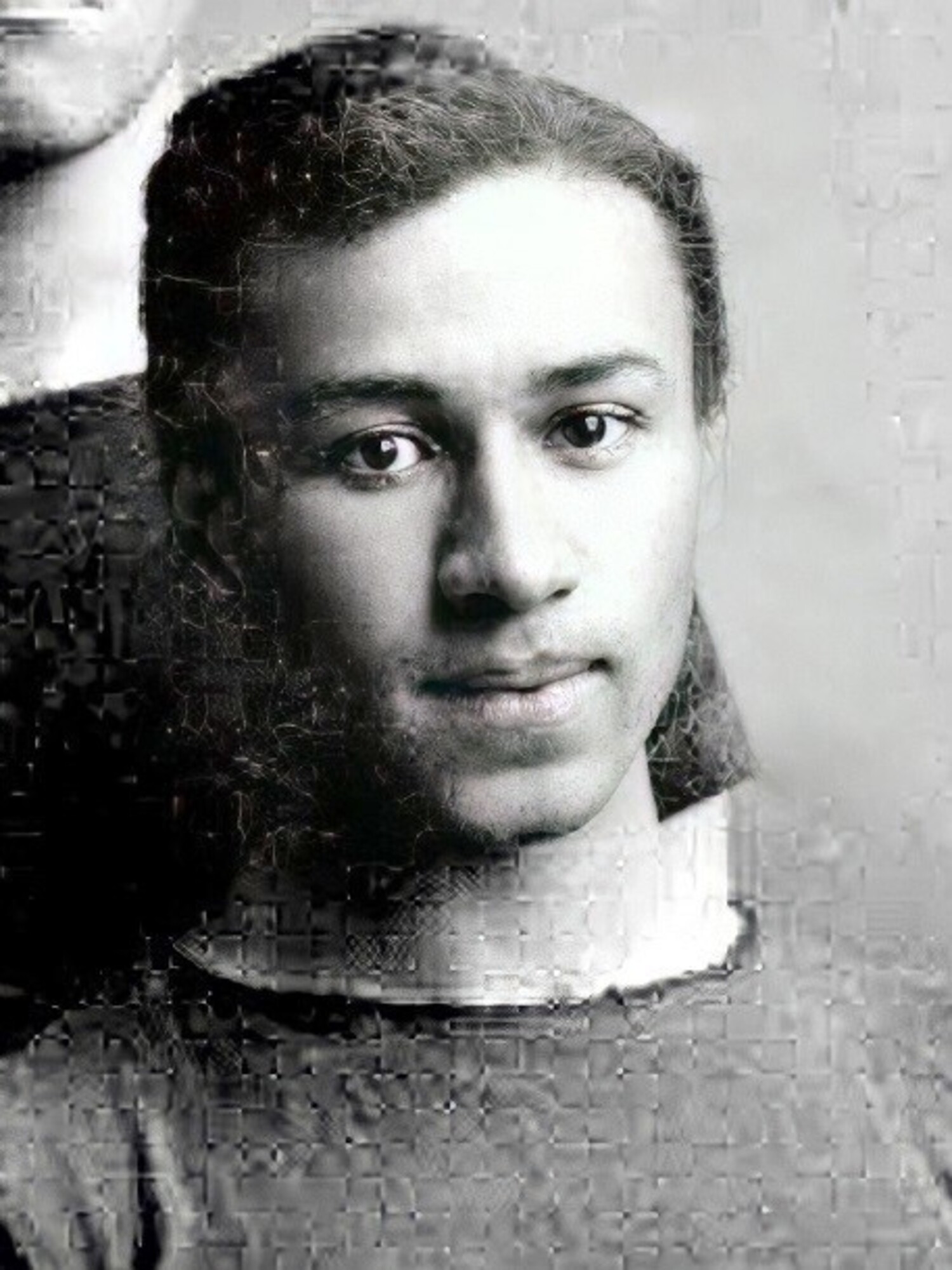

And, a headstone was finally placed on George Poage’s grave, with his graduation photo and words taken from Homer’s Iliad: “Of matchless swiftness, but of silent pace.”

A very fitting summary of a fame that burned twice as fast and expired much too soon.

Poage Park (500 Hood St, La Crosse, Wisconsin)

Poage Park (500 Hood St, La Crosse, Wisconsin)

recent blog posts

December 17, 2025 | Michail Takach

December 16, 2025 | Michail Takach

December 01, 2025 | Dan Fons

The concept for this web site was envisioned by Don Schwamb in 2003, and over the next 15 years, he was the sole researcher, programmer and primary contributor, bearing all costs for hosting the web site personally.