Eldon Murray: the father of gay liberation

"It is not what life does for you, but what you do with life that counts."

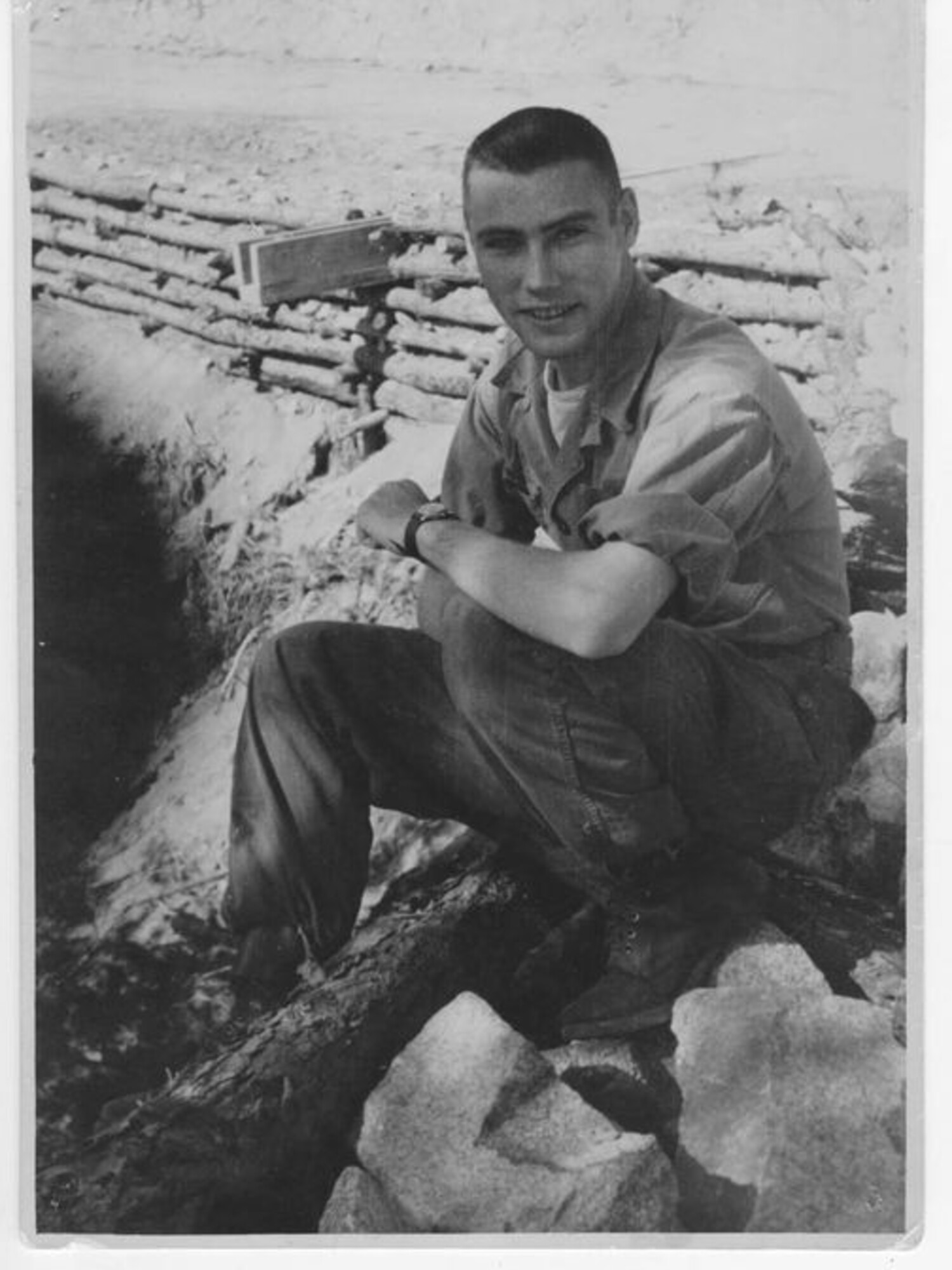

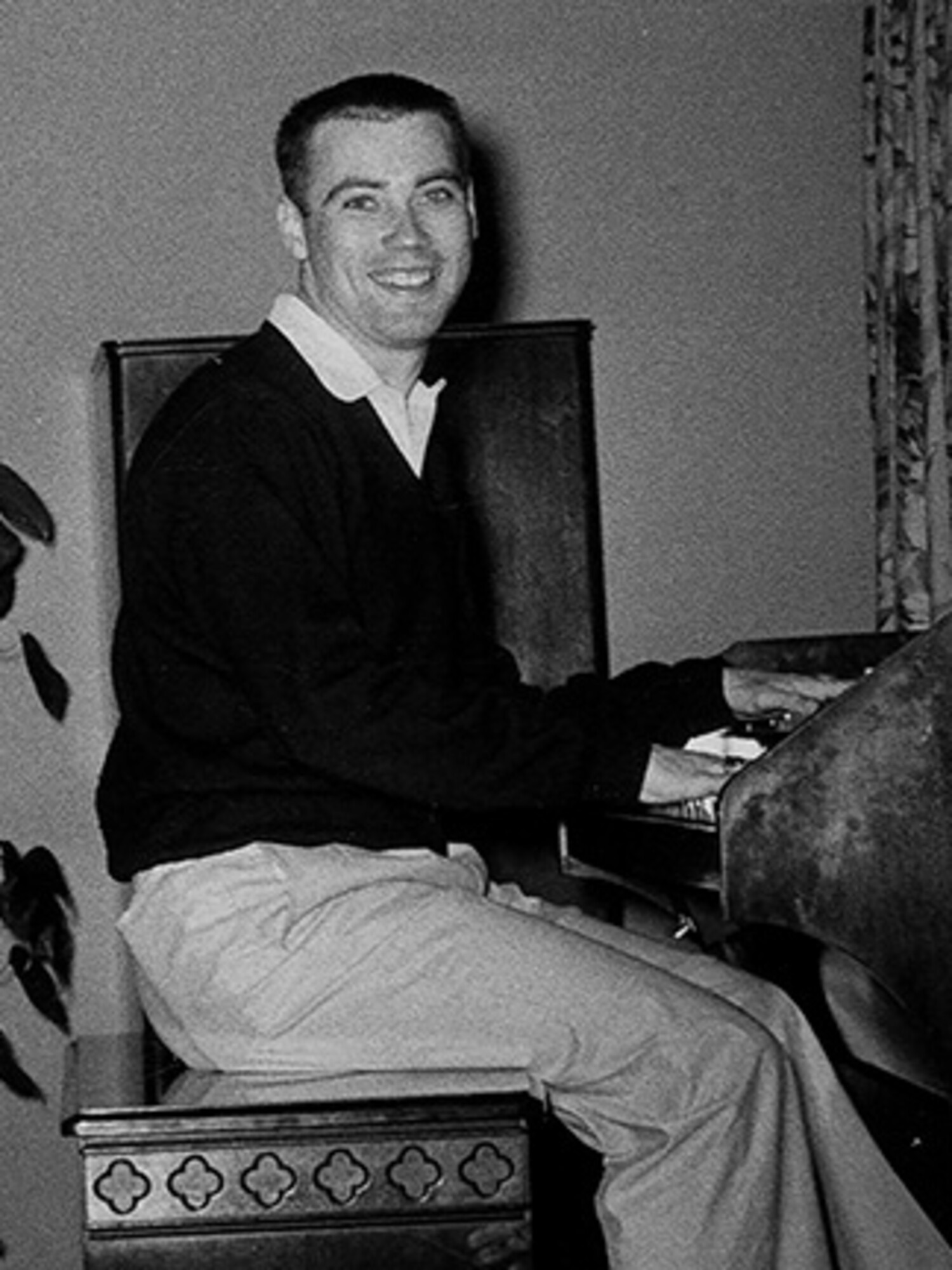

When Eldon Murray (1930-2007) was a teenager, he sought to find some reflection of himself, or people like himself, in the world.

It was very easy to believe, at the time, that no other gay people existed – and that’s what society wanted his generation to believe. There was only crushing homophobia everywhere he turned.

Eldon scrapbooked news clippings for decades, highlighting or underlining code words used to describe homosexuals. The headlines always included words like “deviate,” “pervert,” “invert,” “molestor,” “dishonorable,” and almost always “criminal.” Eldon knew what these words really meant. He’d often cross them out and replace them with his own word. GAY.

The voice of a nation

Eldon's historic contributions to the national "gay press" can only be described as humbling.

On January 13, 1958, the US Supreme Court ruled that ONE, America’s first national gay mail-order magazine, did not violate federal obscenity laws. “Just because a publication contains homosexual content,” ruled the judge, “does not automatically make that content obscene.”

The ONE lawsuit opened the floodgates for a national gay press, over a decade before Stonewall, fostering a national nightlife network for men in the know – and the formation of an interconnected gay experience in America’s largest cities. Publications like the Lavender Baedeker and the Damron Guide were critical in creating true community for the first time ever.

By the time ONE ceased production in December 1969, the Stonewall Uprising had inspired gay mail- order “magazines” in almost every major American city – except Milwaukee. These were not well- written, well-organized, well-conceived or sustainable publications, much more like the zines of the 1990s than actual magazines of today. Still, they were better than nothing, and they were as rare as they were scandalous.

Counterculture magazine Kaleidoscope began to cover the gay movement in February 1970, following Gay Liberation Organization’s activities. They tackled topics ranging from gay dance to vice squad raids to the mutually non-exclusive intersection of faith and sexuality. Gay Liberation Front and Radical Queens staged a "hostile takeover" of Kaleidoscope in January 1971, which covered the state's first Gay Pride March & Rally and Gay Pride Week 1971. DJs from 98.3 WZMF appeared naked in the issue to protest gay persecution.

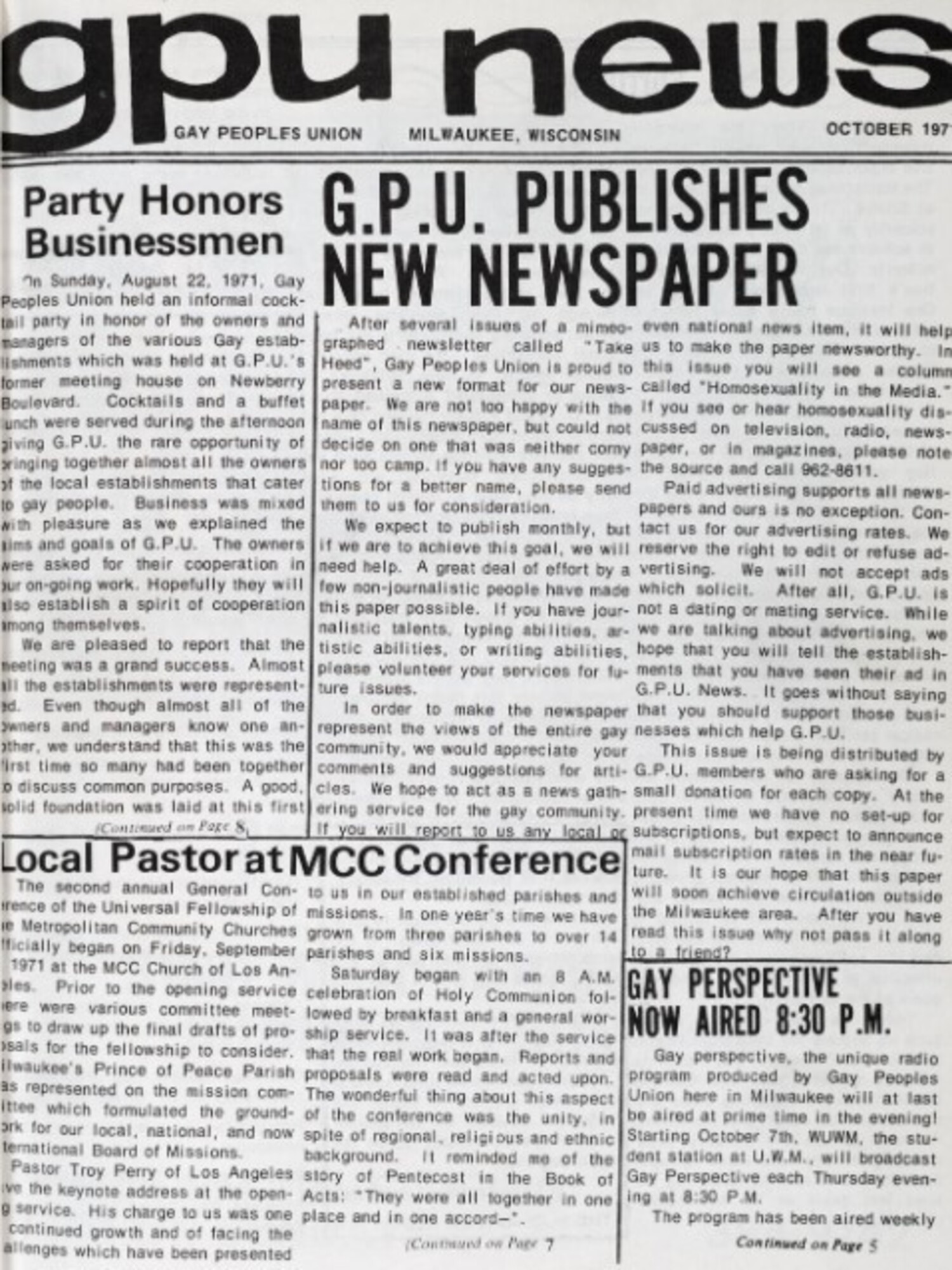

Inspired by these upstarts, Eldon launched GPU News in October 1971. It was the first Milwaukee gay monthly and the voice of Gay People’s Union for the next ten years. GPU News, and later, its less sophisticated bulletin, the Milwaukee Update, provided some of the nation’s best gay rights coverage. Eldon was nominated to lead the publication, and he agreed because he "saw the need." He often wrote under the pen name Sam Edwards.

"Until recently, Black heroes were omitted from the history books, their accomplishments being ignored entirely. Blacks are busy putting [themselves] back into the pages of history. We must do the same thing ... We must remove the whitewash carefully so that the true picture will emerge and gays both historic and modern can take their rightful place," wrote Eldon in the March 1973 GPU News.

GPU News began with a heavy Milwaukee focus, but as the publication became nationally known, heavily subscribed, and widely recognized, content shifted to a wider range of national topics. The magazine received ongoing acclaim for its exceptional journalism and literary quality. GPU News was considered higher-quality content than its contemporaries, including After Dark, Michael's Thing, Gay Life, Christopher Street, and even The Advocate.

The publication received tremendous support from local advertisers. Annual subscriptions were only $10.00 for twelve 50-page issues. Most importantly, GPU News promised confidentiality to subscribers: their names would not be lent, sold or otherwise available to any other organization. Costs were subsidized through the sales of pro-gay posters, pins and t-shirts.

In later years, Eldon published GPU News under a nonstock corporation, Liberation Publications, to ensure copyright protection. However, throughout its entire lifespan, the magazine was a nonprofit publication with an all-volunteer staff. On its tenth anniversary, GPU News bashfully proclaimed itself the longest-running English-language gay magazine in the world, with over 5,000 subscribers.

At the same time, they lamented their ongoing financial struggles, the short lifespan of most gay liberation publications, and the understated role of the small press in preserving truth and justice in society.

GPU News is a rare and insightful snapshot of 1970s gay liberation at its peak. Eldon faced the impossible role of balancing editorial content to satisfy an increasingly diverse, and also increasingly divided community. Letters to the editor -- and Eldon's thoughtful responses -- reveal many frustrations that continue to challenge LGBTQ organizations today. Female critics accused GPU News of being too "male-focused" and Gay People's Union a sexist organization. Other writers complained the political content was too "heavy" in an already hard world. The magazine focused on gay and lesbian lives, without creating any space for the "transsexuals" of the time. People of color often did not feel seen in GPU or its publications. Although Eldon always called for his critics to join the movement, and help create the solutions they sought, few rose to the challenge of participation.

"It is easier to criticize and condemn than contribute," wrote Eldon in 1974, "and how I often wish that were not so."

After a decade of leading the gay rights movement as a second full-time job, Eldon Murray was exhausted. Already operating on a shoestring budget and a skeleton crew of volunteers, GPU News abruptly ceased operations in 1981. The final published issue offers no explanation for the magazine’s end, but GPU records confirm that a lack of volunteers made ongoing production impossible.

Today, the full series is available to view online at the UWM Digital Collections website.

GPU News launched a 47-year legacy of continuous gay press that ended with the closing of the Wisconsin Gazette in September 2018. From Milwaukee Calendar in the 1970s, to RAGG and InStep in the 1980s, to Wisconsin Light and Q*Voice in the 1990s, to OutBound and Queer Life News in the 2000s, Milwaukee was fortunate to have local publishers sharing the diverse and dynamic voices of our community. Quest Magazine – based in Green Bay since 1994 – set a new record as the longest-running Wisconsin LGBTQ publication and promptly ceased production after 25 years. Our Lives, the last remaining LGBTQ print publication in the state, celebrated its 100th issue in April 2024.

Today, Milwaukee no longer has a local LGBTQ publication. Even the state’s legacy newspaper, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, vacated its historic downtown headquarters and downsized its operation in 2020.

From celebration to crisis

1981 was a real turning point for Milwaukee's LGBTQ community. GPU News ceased publication, Gay People's Union was evicted from its longtime home at the Farwell Center (1568 N. Farwell,) and organizers were so disenchanted by the lack of support for a community center that GPU itself began to fray at the seams. Simply put, people were burnt out.

"The batteries of the most active people in the movement have long ago run out with no way to recharge," said GPU founder Louis Stimac.

1981 was also the year that AIDS arrived in New York City. Shortly after Wisconsin's hard-won victory as the Gay Rights State, the first AIDS case was diagnosed in Wisconsin. The 1980s became a decade of survival, not advancement, and all of the community's resources were redirected to the crisis.

While he lost countless friends to AIDS, Eldon was deeply wounded by the loss of his close friend and comrade, Alyn Hess, in 1989.

"It is not only the gay and lesbian community that has suffered a loss, it is our whole community," said Eldon. "Knowing he had AIDS was difficult for Alyn, because he had so many bridges to cross and so much left to do in his life."

A legacy that lives on

In 1998, the One National Gay and Lesbian Archives recognized Eldon as one of the nation’s top 30 gay rights pioneers. He’d already received numerous local awards, including Wisconsin Senior Statesman, Milwaukee County Senior Citizen Hall of Fame and Cream City Pace Setter. In his senior years, he saw the risks and costs of social ageism, realizing what a historical barrier it had been in the LGBTQ community.

Donna Utke, one of the founding members of GPU, died in 2001. Eldon reflected on their adventures together, including the time they infiltrated a religious conference disguised as husband and wife to speak on homosexuality. The conference forbid gays and lesbians to attend, so the two presented as "an old married couple from the suburbs."

"Donna was a good listener, who cut right to the point with solutions to every problem," said Eldon. "The movement will miss her."

At the turn of the century, Eldon reflected on the future.

"If we make as much progress in the next 30 years as we have in the last 30, I would be very pleased," he said. "There’s still things to be done. The rights you have must be constantly guarded, or they’ll be taken away."

Like Alyn Hess, Eldon had another 30 years of things to do. However, his health began to decline.

After a series of cardiovascular issues, Eldon got his estate in order. He donated his extensive papers to the University of Wisconsin. In recent years, the UW Archives digitized the Gay People's Union Collection for on-demand digital viewing.

He also founded the Eldon Murray Foundation, so that his tradition of founding and mobilizing would continue after he was gone.

"He knew how hard it was for new groups to get seed money," said friend John Terhardt. "He wanted everything to go to a foundation, with grants to LGBT causes and projects."

Eldon passed away March 5, 2007 at the age of 77.

"He was our Cesar Chavez," Bill Meunier told the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. "He was our Martin Luther King. This guy was on that level for us. He was in a class by himself."

The Eldon Murray Foundation is administered by the Greater Milwaukee Foundation.

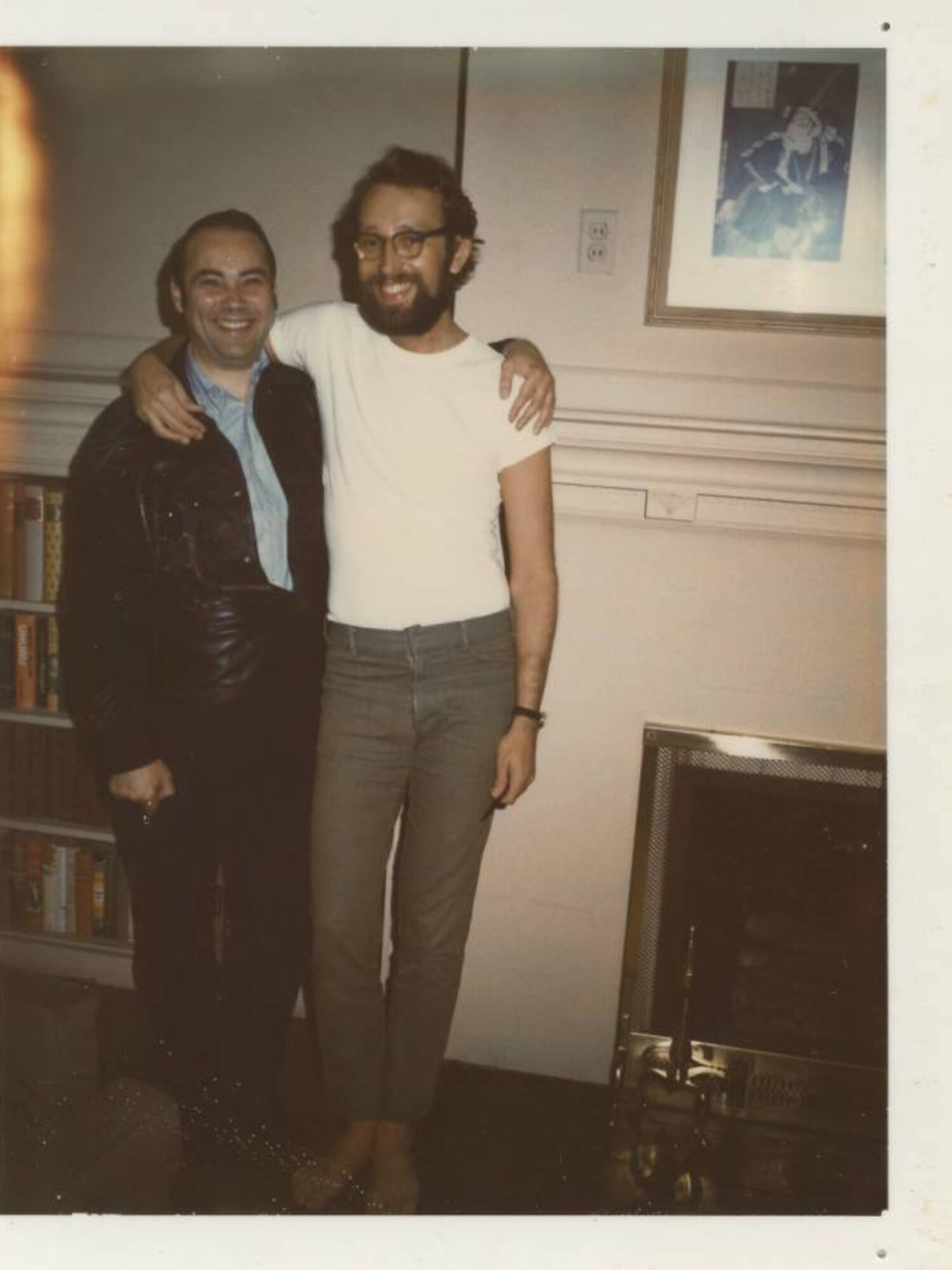

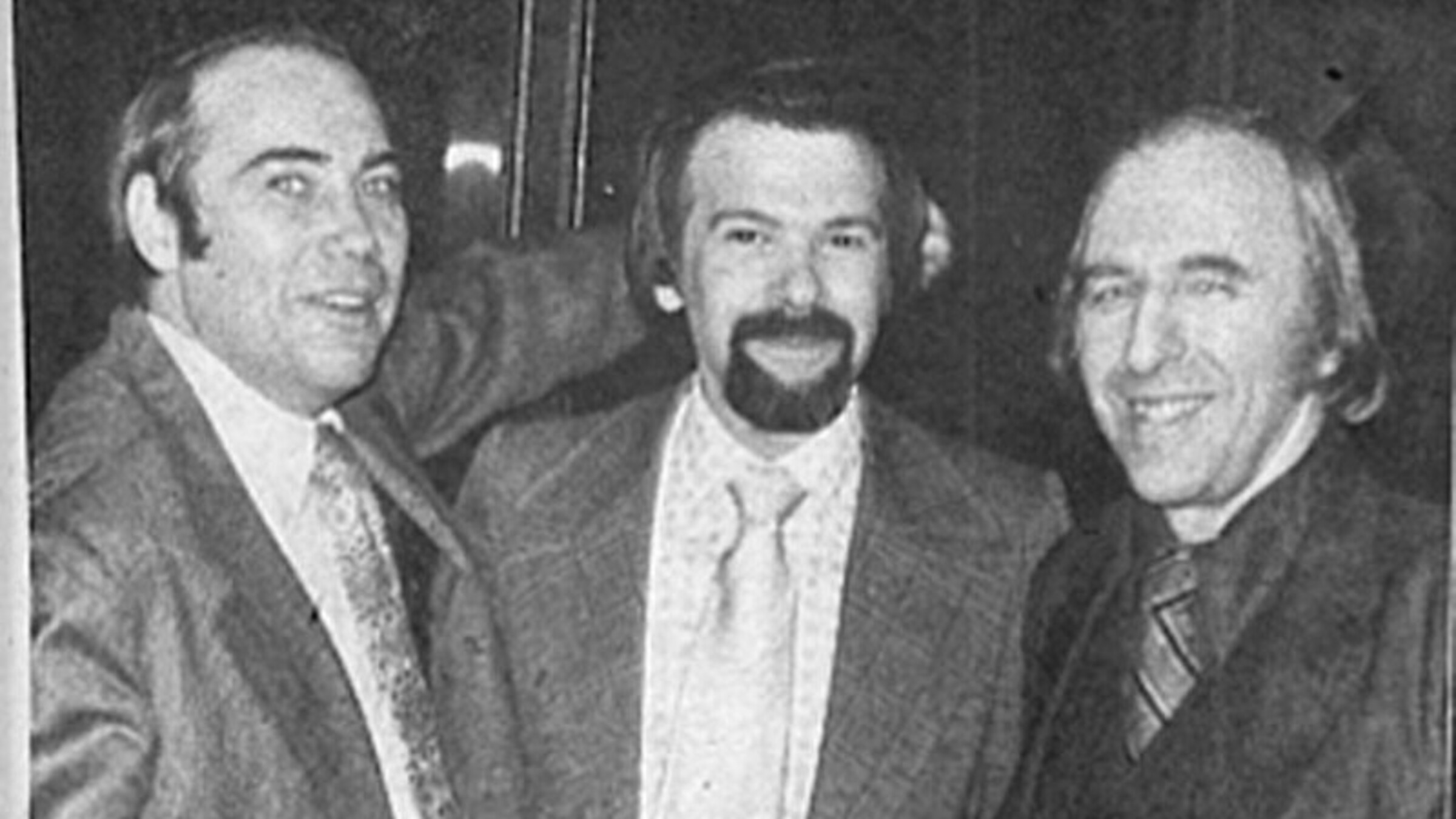

Eldon Murray and Frank Kameny

Eldon Murray and Frank Kameny

recent blog posts

December 17, 2025 | Michail Takach

December 16, 2025 | Michail Takach

December 01, 2025 | Dan Fons

The concept for this web site was envisioned by Don Schwamb in 2003, and over the next 15 years, he was the sole researcher, programmer and primary contributor, bearing all costs for hosting the web site personally.