Del Slowik: celebrating the Golden Age of Club 219

“There’s always going to be bad moments in life. You just have to find the blessings in those moments.”

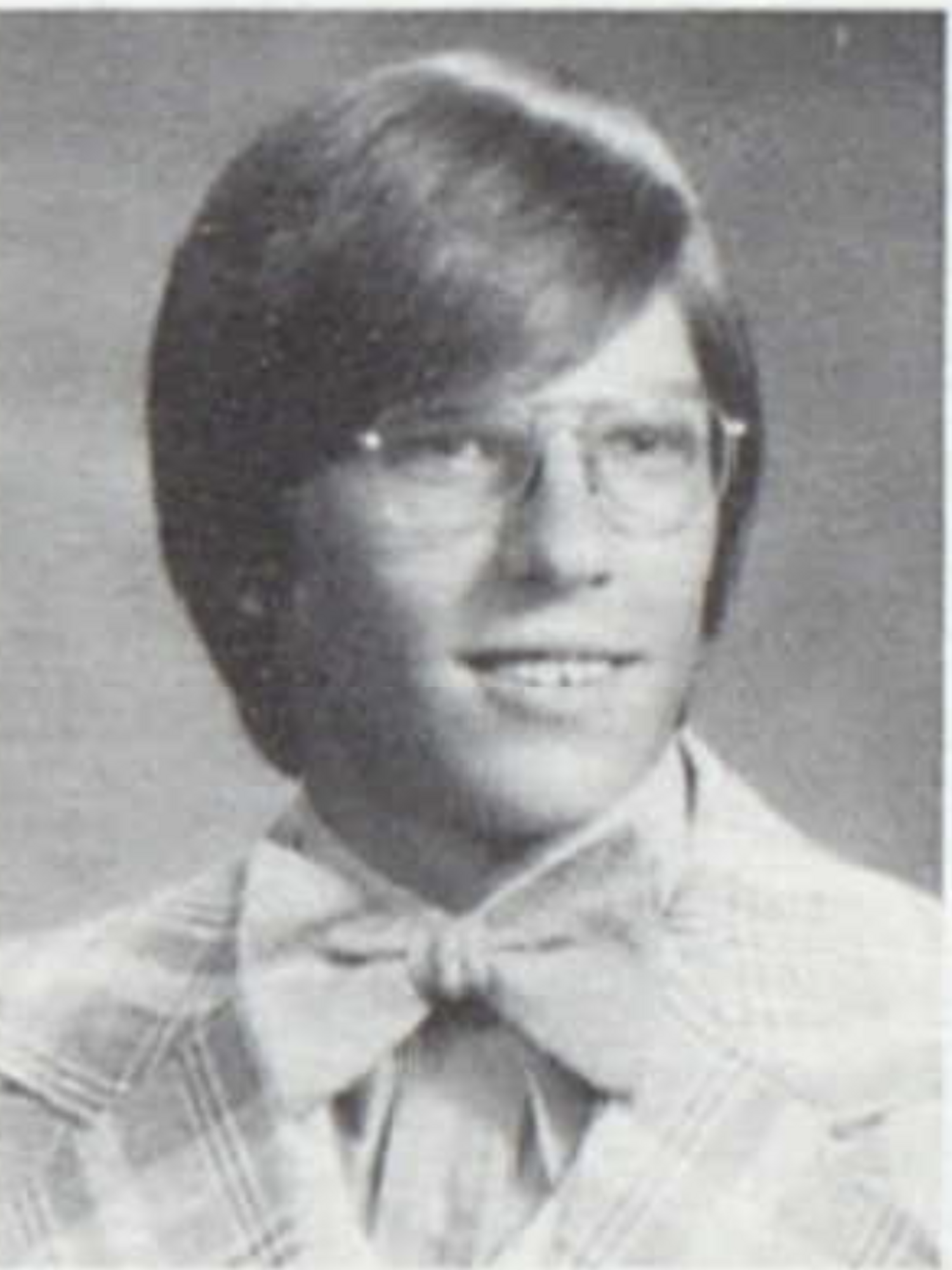

Del was born in 1957 and grew up in Franklin, Wisconsin in the ‘60s and ‘70s. At the time, Franklin was a rural community, and Del’s neighbor was a 40-acre functioning farm.

His parents weren’t able to attend college themselves, so they placed a high value on education. His father worked at the Falk Corporation as a supervisor, but wasn’t able to advance due to the lack of a college degree. So, his main ambition was making sure all his kids went to college.

“Nobody’s ever hurt with education,” said Del. “Learning from other people’s experiences, especially those different from your own, is so important. I grew up in a white, Catholic, middle class family, but we welcomed the first Black family moving into Franklin. It was beautiful to me, but I remember people being aghast. I also remember my father saying ‘what’s the big deal? They are hard-working taxpayers just like us.’

“My father had been through World War II. He worked closely with Black and Hispanic people. He really challenged us to see everyone as equals.”

During sophomore year, Del moved in with a friend near the university. Now, he could really explore what GPU News had to offer. The first gay bar he visited was the Wreck Room.

“I walked in there, pretty non-chalant and not know what to expect,” said Del. “Their advertising always had these very manly, very masculine men, so I was frightened as hell, not knowing what I’d get myself into. I walked up to the bar and I didn’t know a soul. Gary Scheuerman was behind the bar, and after two drinks, he asked me if I was new, and that started my whole history of being attracted to bartenders.”

“Even then, I had this low self-esteem,” said Del. “People always said, ‘you just don’t know how handsome you are.’ Well, I walked into this bar and wound up with the bartender for six months.”

“Tony Canfora, my future partner, was actually working at Wreck Room at the time, and he knew Gary’s history of not having any long-term relationships. So he told Gary, ‘when you’re done, he’s going to be mine. He’s handsome, he’s intelligent, and I’m going to go after him. And he was serious. Well, guess what? After Gary dumped me that’s exactly what happened.”

“I was at the gay beach north of Bradford Beach, when Tony walks up to me on the beach and said hi,” said Del.

“He said, Robert Uyvari and I are opening up a nightclub, and I would like you to be one of our bartenders. I said, ‘wow, this is the weirdest come-on,” because I’d never tended a bar. But Tony said he would teach me how to become the best bartender in Milwaukee. And I agreed, on the conditions that he was my boss, and I was his employee, and he wasn’t going to take advantage of me. At this point, I had scruples, I guess, but I had also just been dumped. But he said, ‘oh sure, fine, no problem,’ and I started working for him.”

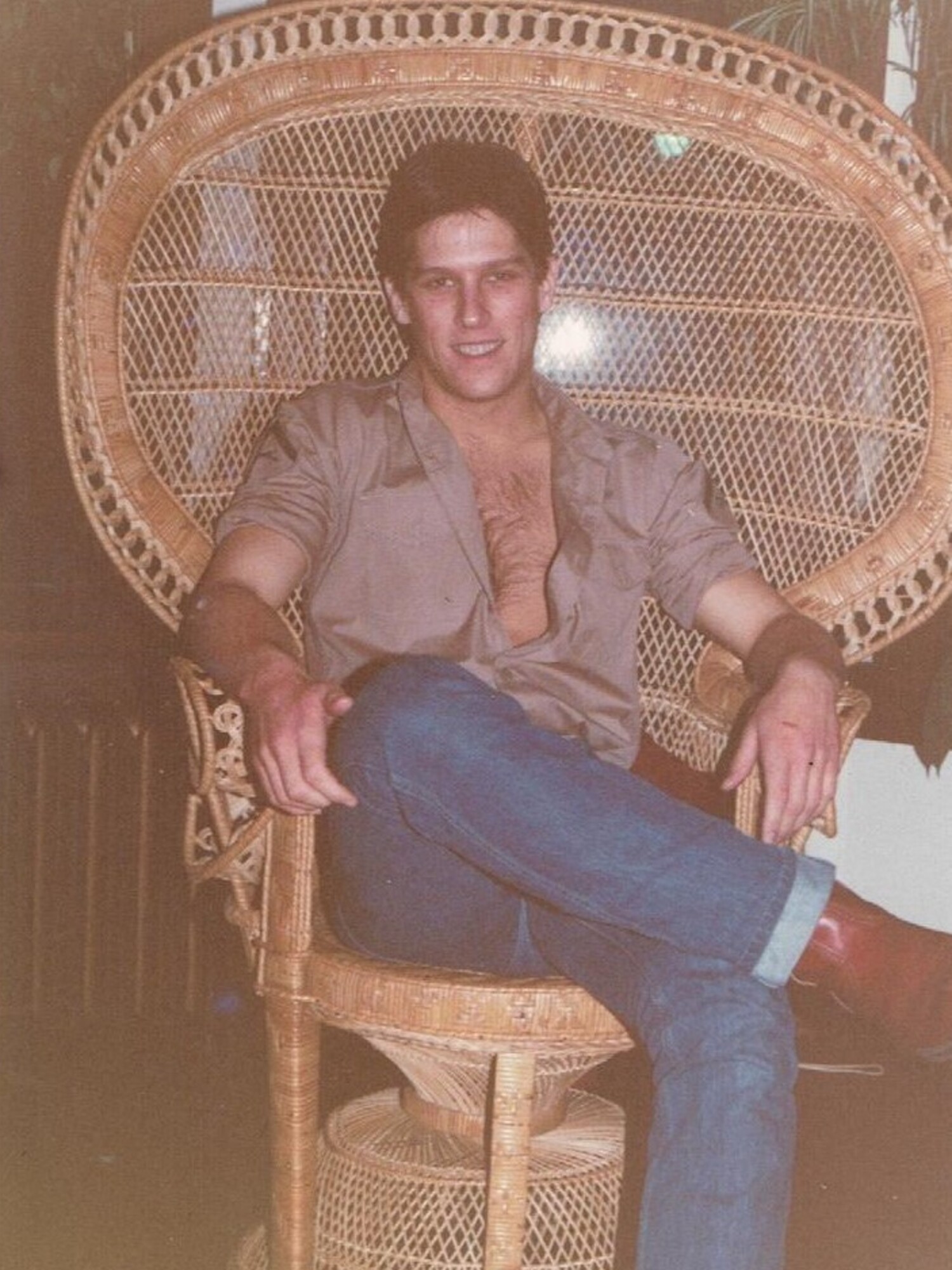

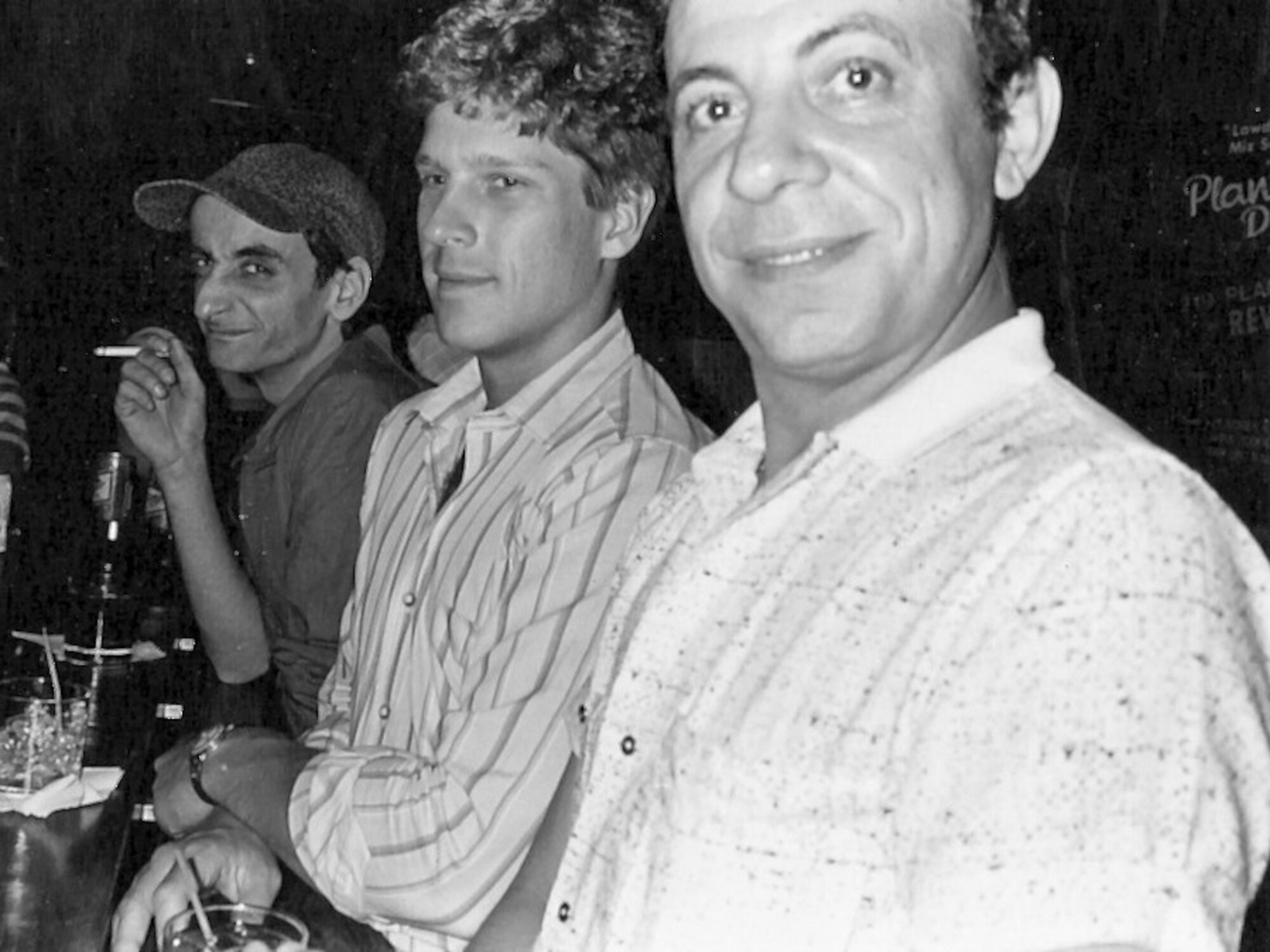

Robert Uyvari, 1980

Robert Uyvari, 1980

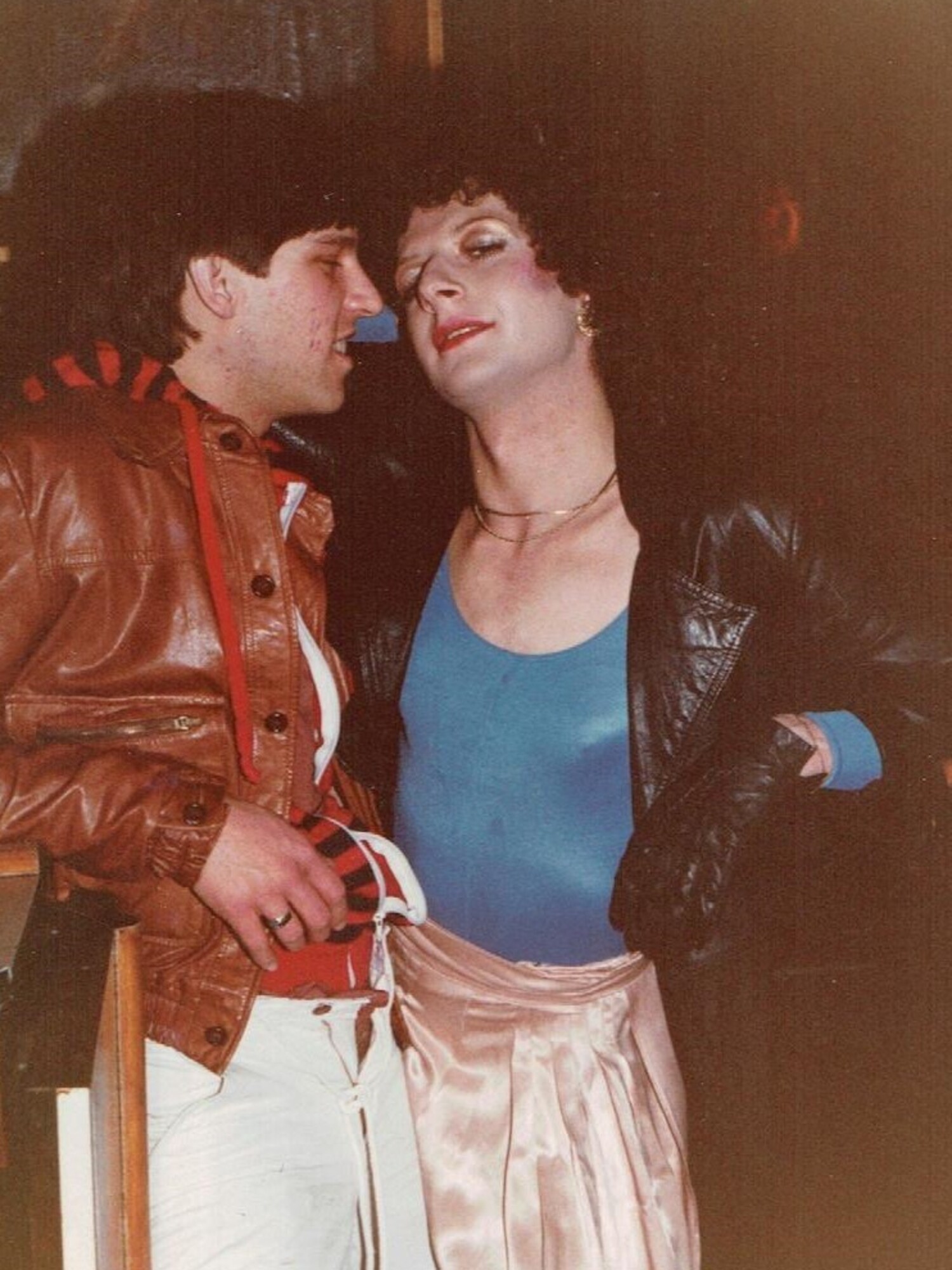

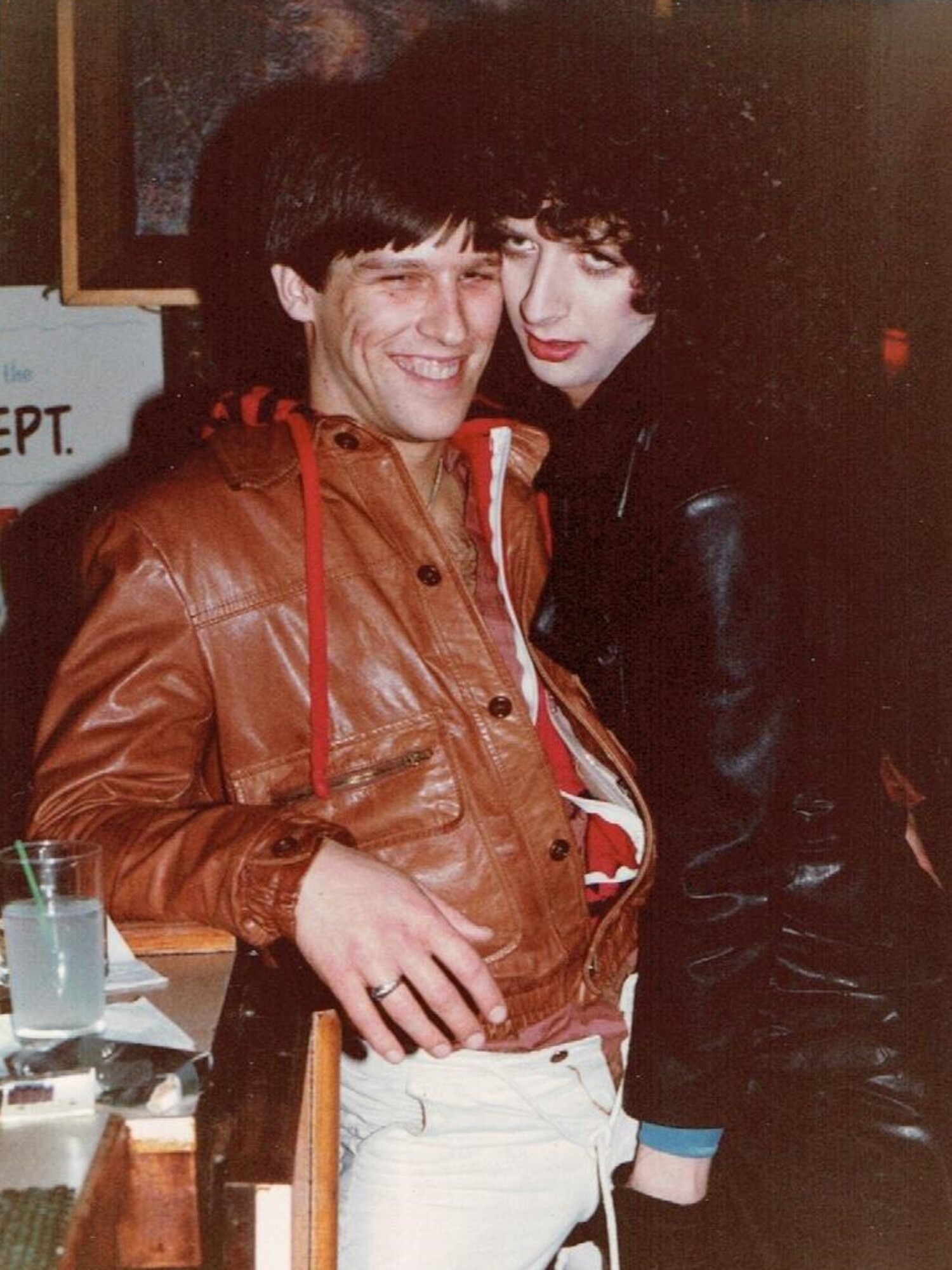

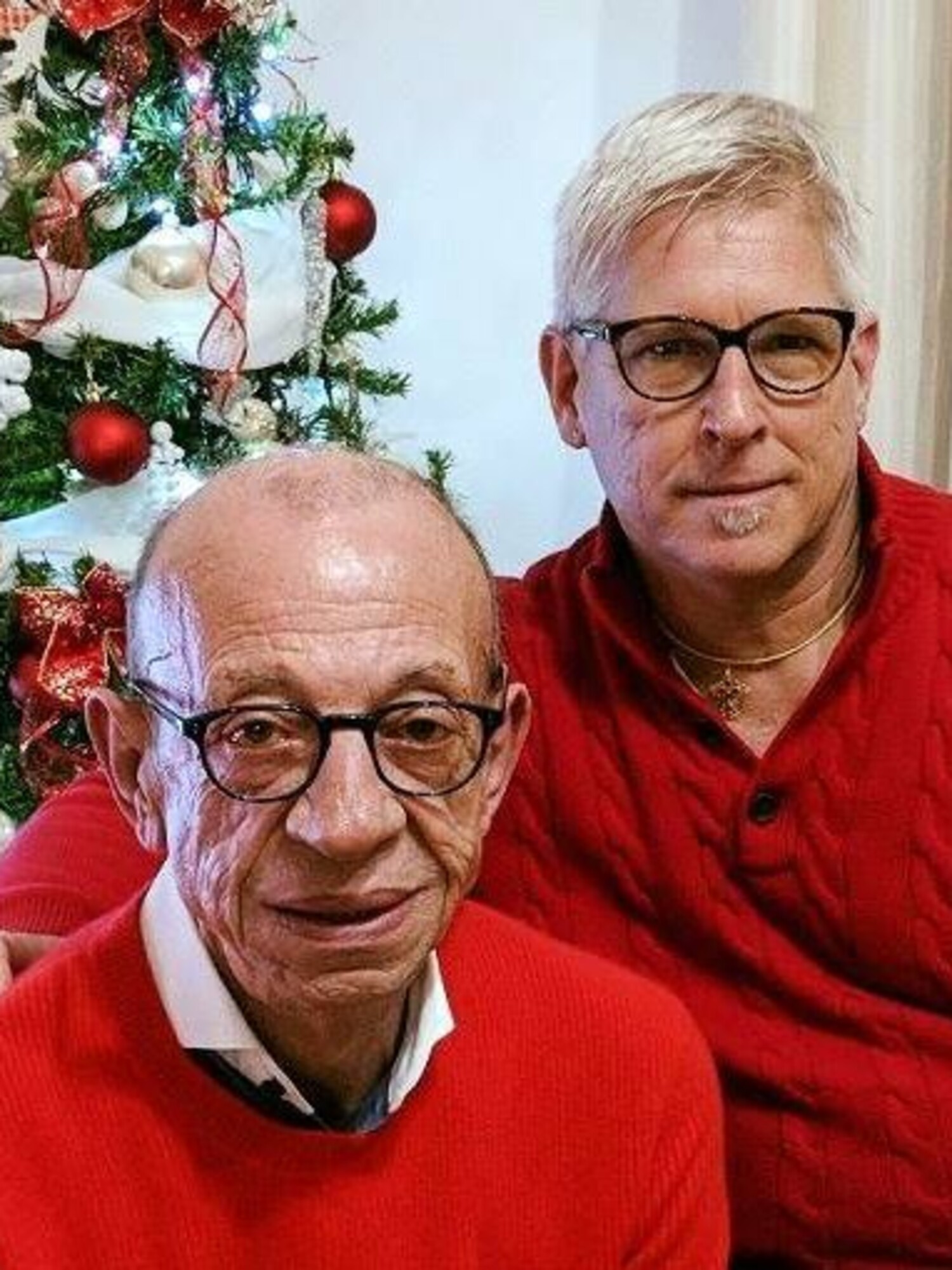

Debi Vance and Tony Canfora, 1980

Debi Vance and Tony Canfora, 1980

Take One: Trash (1980-1981)

Tony was born in Sicily, where he was a small-town shepherd boy in his childhood. He came to the United States by boat age 9 and ended up in New York City, where he ate his first American meal: a hot dog. He grew up around Brady Street, then a heavily Italian area, and worked at the Peter Sciortino Bakery.

Tony met Robert Uyvari through his childhood friend, Gene Olson, and they began a romantic relationship. However, after a disagreement with Robert, Tony began dating a woman. He decided he wanted a family, so the couple married, and he ended his romantic relationship with Robert. However, Judy and Tony didn’t last long and Tony’s divorce led to his ability to get together with Del. Tony’s relationship with Robert lasted for a lifetime.

Trash, the concept bar that Tony and Robert were planning, was a complete reversal of the Circus Disco (219 S. 2nd St.) it replaced.

“They’d stripped the space of all the glamour Circus was known for,” said Del. “The carpeting on the walls, the crystal lion chandelier, the mirrored walls, everything. Robert had just returned from San Francisco, and the trend there was minimalism: black walls, dark rooms, low lighting. They’d planned a dance bar upstairs and an exclusive members-only leather bar downstairs.”

Trash was absolutely packed. There were only three gay dance bars in Milwaukee at the time: Your Place (813 S. 1st St.,) The Factory (158 N. Broadway,) and Circus, and dancefloors were in high demand.

“Trash was very, very successful, but it opened and closed within six months. And here’s why.”

Although Robert and Tony were paying rent, they didn’t have their own licenses or permits. The apparent owner of the Circus, had subleased the bar to Robert and Tony, while under a land contract with Jimmy O’Connor, former owner of River Queen and the “Telephone House” (German American Bank, 2nd and National.) Somehow, Jimmy O’Connor didn’t get paid, so he came into the bar one day with his body guard and Sheriff and said “sorry, you’re closed.”

“Tony said, wait, we’ve been paying rent! Jimmy said that he owned the building and had not received any money!” said Del. “So it was closed down. We were shocked.”

“I went to work at the Wreck Room in the Cell. Tony went to work at the M&M Club. We were no longer employee/employer anymore, so I said to him, ‘just marry me and get me the fuck out of here.’ And he said, ‘are you serious?’ And I said absolutely.”

“One night, Tony asked me to meet him at Your Place (813 S. 2nd St.) I sat down, and he said, ‘are you going to be with me or not?’ and he opens this jewelry box and reveals this big gold ring with four or five diamonds. It’s sparkling all over the place. I’m going crazy. I realized ‘this is how people get engaged.’ And that’s exactly what it meant for us.” “Tony’s wife wasn’t happy with our relationship. She found out I was attending UWM and hinted that she could ruin my academic career through her connections. Tony quickly finalized the divorce.”

That moment started a relationship that lasted 38 years.

Take Two: Club 219 (1981-1989)

Del and Tony doubled down on negotiations with Jimmy O’Connor to get the land contract for themselves. Jimmy Zingale, a longtime benefactor of Milwaukee gay bars, was also involved in the deal. Soon, Club 219 was on its way to happening.

Tony wanted to reopen the bar, but he had some challenges ahead of him. Due to a long-ago disorderly conduct charge, he was unable to pass the required police background checks for the tavern license, so Del was named as the license holder. Tony’s sister represented the business along with Del on the land contract. After all this work to get the bar open, they submitted a reopening proposal to the Common Council that was rejected over and over.

“One day, I was cleaning the bar, when the phone rang,” said Del, “and the person said ‘I can’t tell you exactly who I am, but I can tell you that the Common Council will never, ever approve your license with the name Trash. You cannot have a liquor license with that name. You need to change the name on the application.”

“So I’m sitting there, alone, in a panic, trying to come up with a name. I didn’t even know where Tony was. And that’s how the name Club 219 came about: I thought, the address is 2-1-9 and it’s a club. So, Club 219. That’s about as innocent as it gets. I ran downtown to amend our application – and we were approved for a cabaret license. Club 219 became the business, and Trash was the lower level only.”

When Club 219 opened, it faced another challenge: an outdated city ordinance that said there could only be two liquor licenses on a block. At the time, there were three bars on the block, but they’d been grandfathered due to the age of the licenses. Sorting out the naming and licensing was especially important – as a new license would never have been issued otherwise.

“Robert wasn’t really happy with the name at first, but eventually he did the logo with the Roman numerals that made 219 famous.”

At this time, Del was working full-time as a second shift nurse, and the drugs and alcohol of nightlife were increasingly fogging up his perspectives.

“I’d get off work at 11 p.m., run my ass down to Walker’s Point, start bartending, and then I’d be out until 3, 4, 5 a.m.”

Club 219 was very, very busy from day one. But, as with any gay bar, Del and Tony knew it would need to reinvent itself every 2-3 years.

“People were fickle,” said Del. “We recognized there was a pattern to how they moved: from Your Place, to 2nd Street, to the Wreck Room and Factory. We disrupted the pattern and just kept disrupting it. We brought it new lighting, we opened up the back garden, we brought in new talent. By our 3rd anniversary, we had a major new competitor: La Cage (801 S. 2nd Ave.) It was time to reinvent ourselves again.”

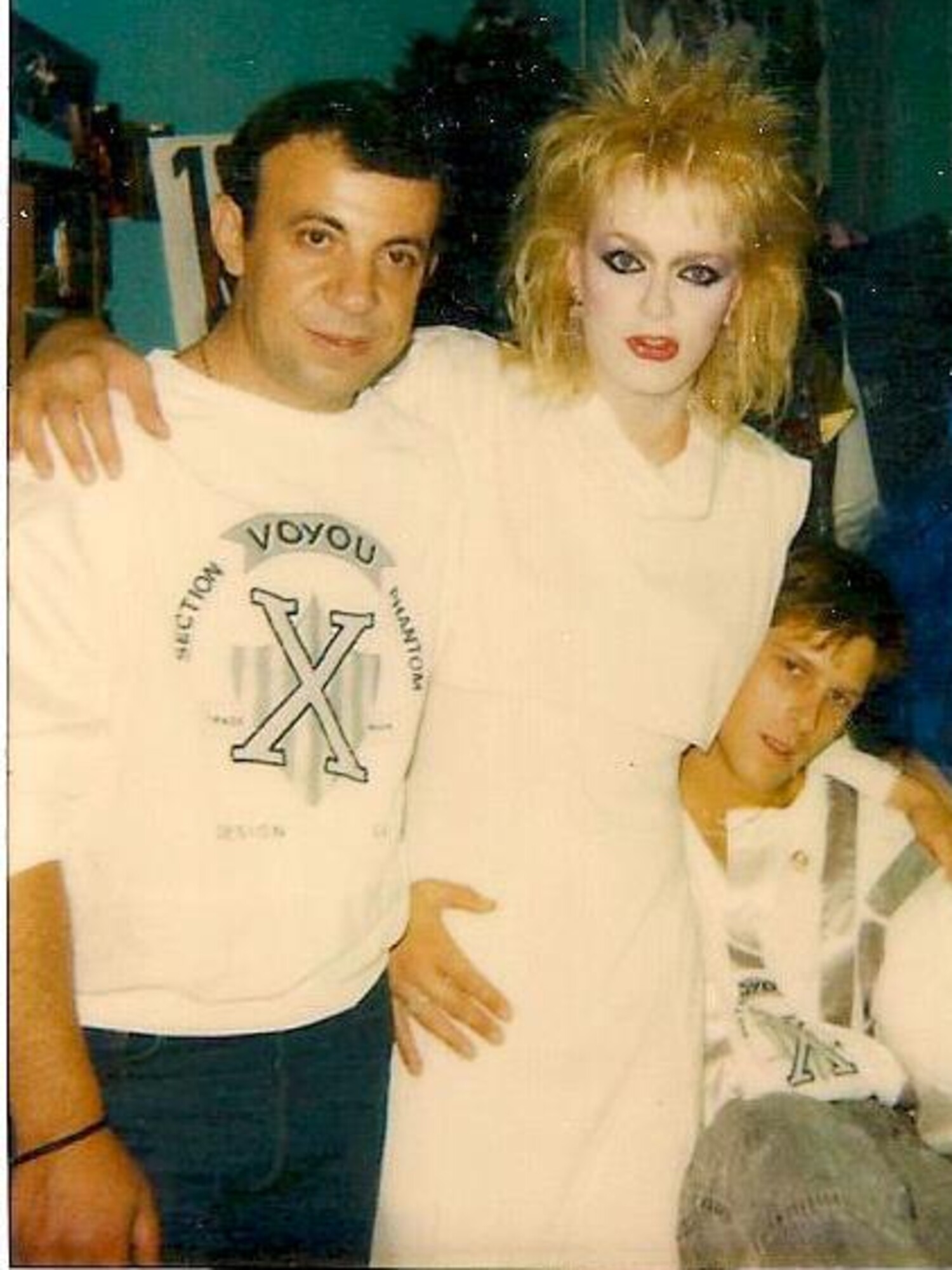

Tony and Del with Miss BJ Daniels

Tony and Del with Miss BJ Daniels

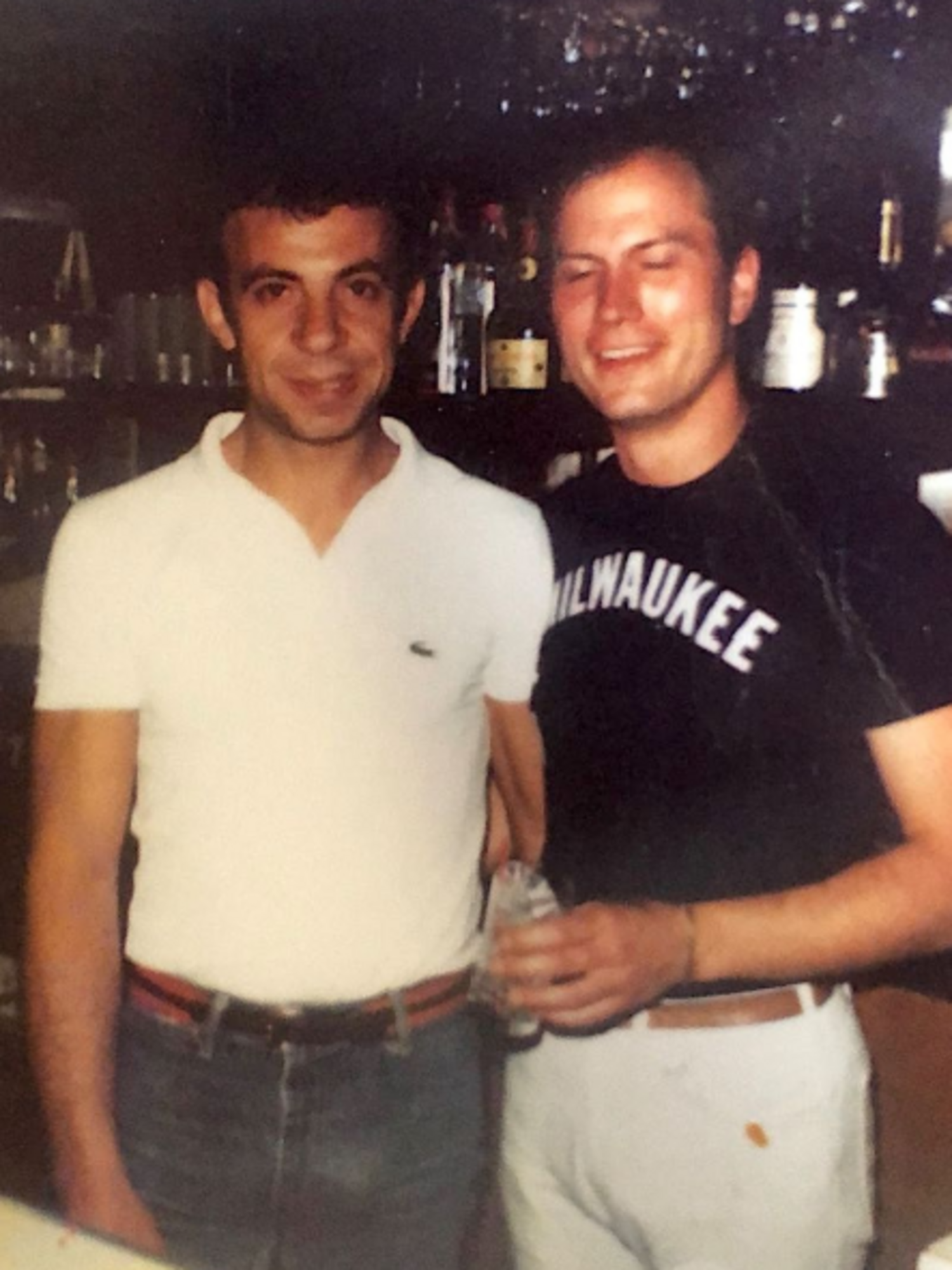

Tony and Rona worked together at M&M Club

Tony and Rona worked together at M&M Club

Caregiving in catastrophic times

During the AIDS Crisis, Del was on the board of the Brady East STD Clinic.

“I remember talk of these strange, concerning cases coming out of New York City,” said Del, “and then hearing about the same type of thing happening in Los Angeles and San Francisco. I remember advising the Board that we needed to be talking to people in Milwaukee. And there were people who actually said, no. There will be a backlash. We can’t talk about this. It’s on the coasts; it will never get here to Milwaukee. People actually believed that. They had no idea how bad it could and would get.”

“And then, cases started to appear in Chicago, and still it was seen only as a big city problem. Chicago is only 90 minutes away from Milwaukee. People go back and forth all the time. Why would it be difficult to believe a disease could travel the same way? I will never forget everyone denying this was a problem.”

“At the time, gay life had become popular. People had gay friends and went out to gay dance clubs. There was this fear of scaring people. And they should have been scared, because by 1983 we had our first case in Milwaukee.”

“I said, it’s here. It’s real. Now we’ve got to say something. It was just tapping lightly on our windows before, and then it was banging on the doors. Now, it’s blown the doors right off. It’s here. It affected more people in my life than I can even count.”

“And oh my God, it was horrible.”

The Golden Age of Milwaukee Drag

Tony, and Gene Olson (a childhood friend and mutual acquaintance) decided to visit Acapulco, but Del stayed behind to watch the bar. While in Acapulco, Tony became enthralled with the drag shows – the music, the lighting, the costumes -- and came back with a brand new vision for Club 219.

“That’s when the Who’s No Lady Review came in,” said Del. “Samantha Stevens was connected to Sam Mazur and Michelle of the Phoenix, and she came in with a stable of highly talented queens. We already had the cabaret license. And now, all of sudden, we were having shows.”

Club 219 was the first Milwaukee area gay bar to pay drag queens for their performances. Rather than working only for tips or a hopeful cut of the door, the artists were actually on payroll and receiving paychecks.

“I loved Samantha. She just had this air of elegance about her. As the shows were progressing, and we became part of the pageant scene, we wound up connecting with Felicia (Jim Flint) and The Baton. We started bringing performers up from Chicago for exclusive appearances at Club 219. Jim said, ‘you can have my performers when I don’t need them, but remember their costumes are all mine.”

Felicia was known for taking good care of his girls, but they were always his property, and he reminded them all the time not to forget. Their high quality performances won them spots on the Oprah Winfrey Show, which boosted their careers and The Baton’s popularity greatly. Soon, they were having shows every night of the week, and even afternoon matinees.

“At first, we paid Samantha to pay the girls, and later we paid the girls individually as employed artists,” said Del. “But we expected quality in return. You needed to have good outfits. You needed to be a good performer. You need to know the words to your songs. There will be no singing ‘peas and carrots’ to fake it until you make it. Not at Club 219.”

“We probably never got to the same level as the big Acapulco shows,” said Del, “but we sure accomplished something special. This little place, in Milwaukee, had stars like Candi Stratton and Mimi Marks. Big names. Huge careers. Mimi was and still is absolutely exquisite. Candi was and still is stunningly beautiful. They’ve done so well for themselves, and I’m so proud to know them.”

“Two shows really stand out in my memories,” said Del. “The first one was B.J. Daniels doing ‘Here Comes the Rain Again’ with actual rainfall onstage. Setting all that up, making sure it was working, all those logistics. And considering the size of the stage, the size of the bar, and the size of audience…. There was such great attention to detail. We worked so hard. Our Halloween and Christmas displays were also otherworldly. We transformed the main bar into a forest, and then flocked the forest white for Christmas. People would come in just to see that. Just to see the detail.”

“The second show was Shante, now known as Alexandra Billings, who came to Club 219 from The Baton,” said Del. “She would sing Broadway showtunes live on stage. Nobody had ever done that before. That was unheard of. It was something you could only see at Club 219.”

Club 219’s cabaret license allowed them to have not only drag shows, but ticketed concerts and comedy acts. From Julie Brown to Pamela Stanley to the Weather Girls, Del and Tony brought in some of the most popular acts on the gay circuit.

“There was an energy at Club 219,” said Del, “and people wanted to be part of it. Looking back, the performers who came to Club 219 were just phenomenal. These were high quality acts. We recognized that we were a small gay bar in Milwaukee, so our ticket prices were always affordable. It was a real experience to see a show. The stage set-up allowed a real audience connection. We really tried to discourage performers from going out into the audience, to maintain the illusion of the performance. Nowadays, the bars aren’t really set up for that kind of illusion, and the performers can’t make it happen on the ground.”

“When the Village People performed, we had lines stretching down the street,” said Del. “Our capacity was somewhere between 160-220. Well, we had a real capacity issue, and then the police showed up to make sure we knew it. That was probably the only time we ever had a problem with the Milwaukee Police Department.”

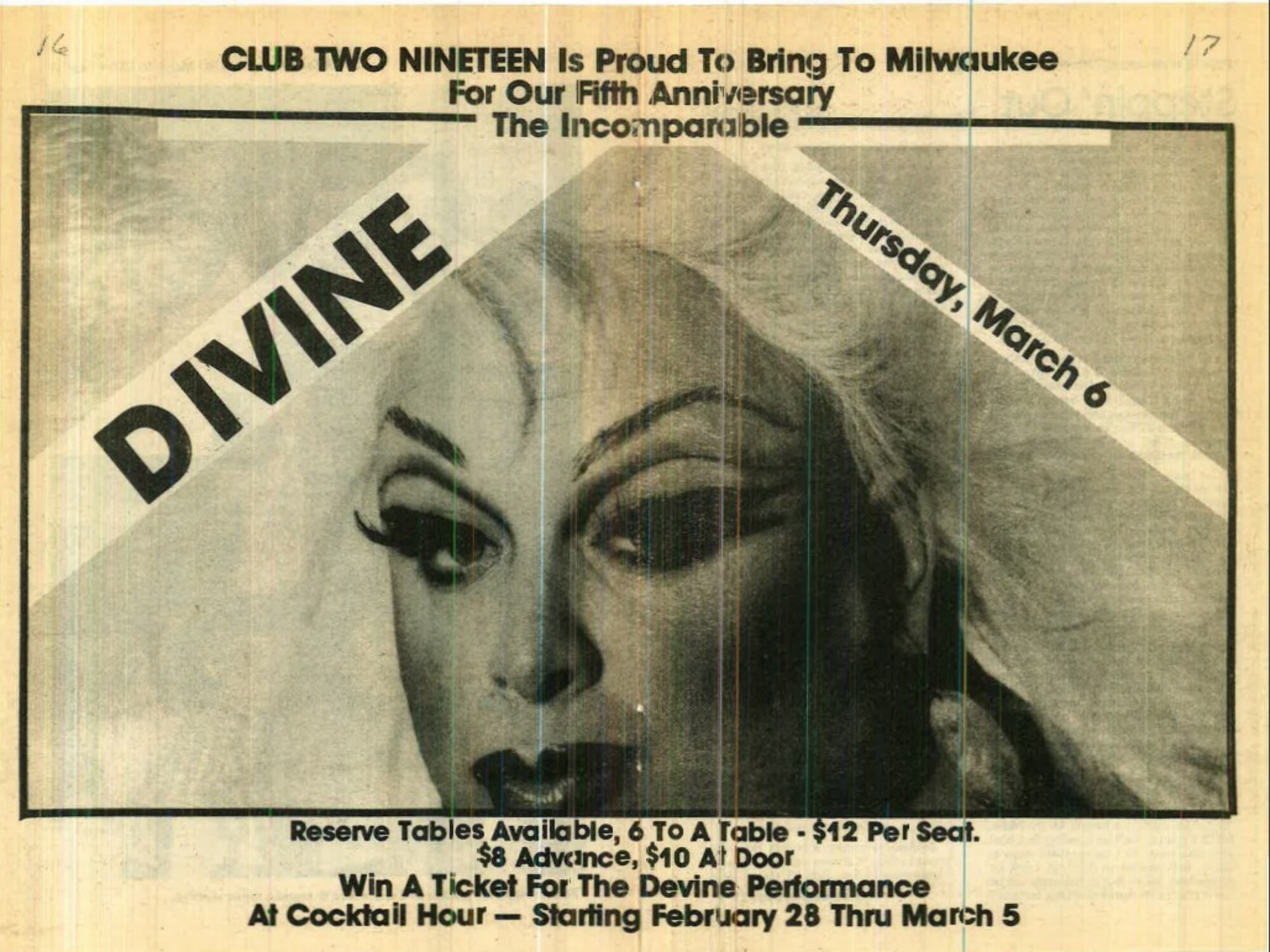

“Divine played twice: March 6, 1986 for our fifth anniversary, and February 18, 1988 for our seventh anniversary,” said Del. “I picked him up at the airport, and he’s really winded, and his legs were really swollen. I remember asking if he was going to be okay. He ended up doing a really, very powerful performance.

“It’s crazy, but Club 219 was her last performance anywhere ever. She died in Los Angeles three weeks later on March 7, 1988.”

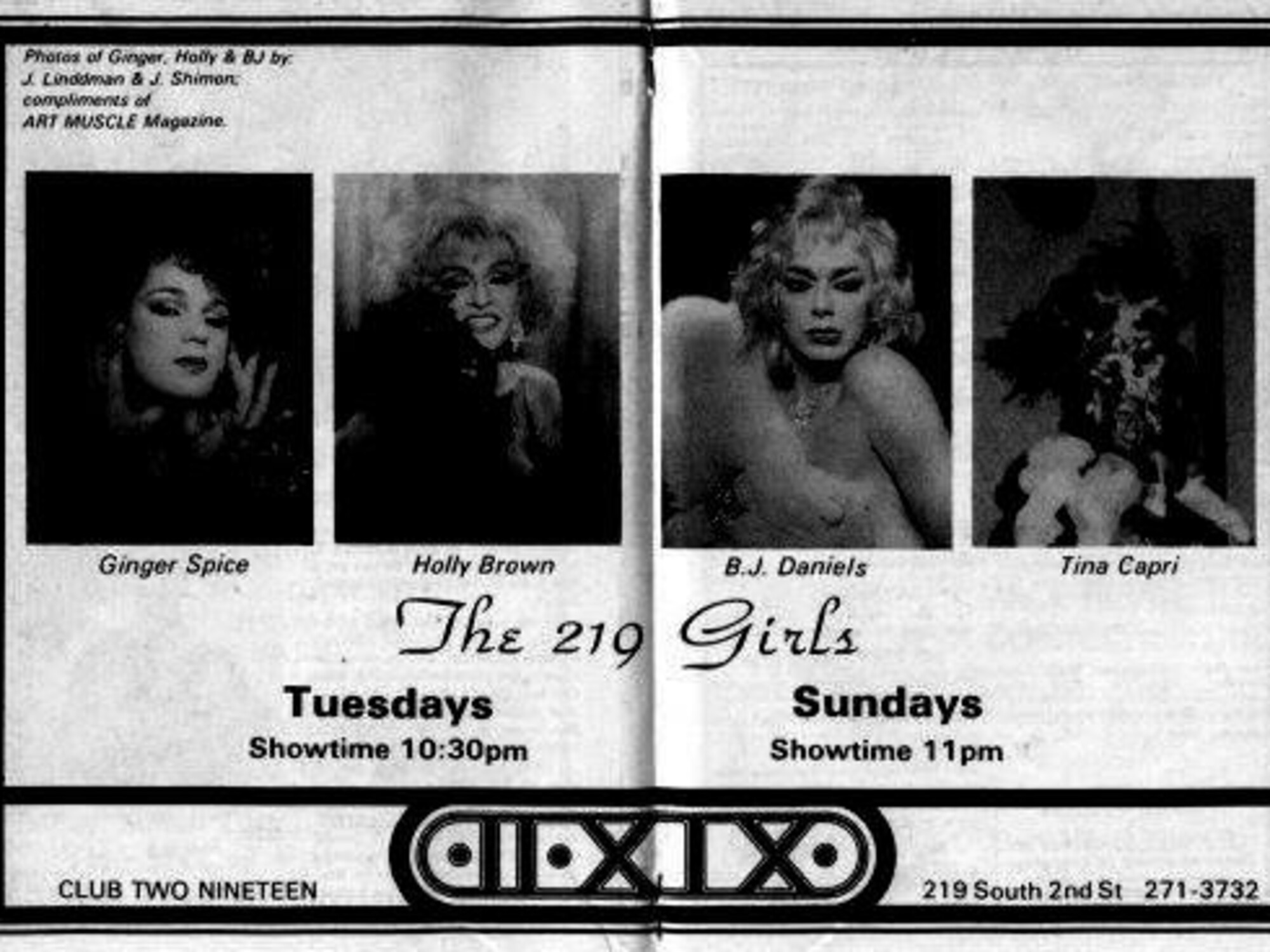

The Club 219 Girls

The Club 219 Girls

Divine performed at the 5th anniversary (1986) and the 7th anniversary (1988) of Club 219.

Divine performed at the 5th anniversary (1986) and the 7th anniversary (1988) of Club 219.

Life in the gayborhood

“The building was just gorgeous,” said Del. “The third floor had 20-foot ceilings with beautiful arched windows. It was built to last centuries. We had always dreamed of having a residence up there, but I decided I couldn’t live above a place like Club 219. I wanted to be able to leave it and go home at the end of the night.”

Del may not have ever lived at 219 S. 2nd St, but someone – or something – certainly haunted the building after hours.

“We would be sitting there after hours, and you’d hear noises in places where nobody could be,” said Del. “Footsteps on the second floor, creaking steps, things like that. Tony named the ghost ‘Harvey’ and he would actually talk to it. ‘No, Harvey, we know you’re not trying to scare us, we understand, it’s okay.’ Several people experienced this over the years, and we could never really explain it. You can say the old building was settling, or groaning, or whatever you want to believe. But this wasn’t that. This was very different. This was the sound of human motion. And I’m sure it’s still there.”

Del and Tony often had roommates living with them, and some of them brought controversy to their house.

“We had Raymond Messick, who was a brilliant, brilliant DJ, until we fired him and he ended up going somewhere else. Well, he wound up in a wrongful death case that involved heroin, a blood-filled bathtub, and body parts in trash chutes. And after getting out on bond, he just completely disappeared. It was just another one of those scandals that colored Club 219.”

Nowadays, it’s hard to believe there were four or five gay bars operating within one block of South 2nd Street, but Del remembers it well. The bar owners actually formed their own coalition, the Business Association of Milwaukee, to represent their interests.

“Everyone was cordial to one another, but we were all so business running our business, so there was very little time to socialize,” said Del. “We were the biggest thing on the block, but we weren’t pulling business from the other bars, we were attracting business for the entire block.”

“The police used to do routine inspections, and I remember one officer getting a bit of a lesson,” said Del. “He walked through the lower level, pointed out the sling, and asked ‘what’s with this?’ And we’d have to explain what it was used for – and also explain it wasn’t being used that way at Club 219. After that, they’d come back occasionally with other officers to look at it. And we’d ask, hey, is anything wrong? And they’d say, oh, no, just checking in. It was like a tour of the zoo!”

Unfortunately, the lower level “Trash” area, later named the “Shaft Bar,” never really succeeded as the exclusive leather bar Robert Uyvari envisioned. The Wreck Room already owned that clientele in Milwaukee, and after Boot Camp opened in 1984, competition increased further. Uyvari’s idea of a leather bar, with dress code strictly enforced, was hard to police within the 219 space. The bar needed two door men, one at the front door and one at the lower level entrance, to make the dress code work. If someone left the lower level to dance upstairs with friends, they couldn’t return downstairs with those friends. Unless a specific leather event was happening, there was simply not enough business downstairs to warrant all the extra staff.

The politics of dancing

Del challenges rumors that Club 219 operated with a “quota” system for performers of color.

“We had the same expectations of all cast members: you weren’t guaranteed a spot in the show, you had to earn it, and you really had to work to earn it. There were no trophies for showing up. We had very high standards, but we paid very well in return. Being a Club 219 Girl was a mark of distinction in Milwaukee. Samantha, Ginger, and BJ were starmakers.”

“We had no restrictions on customers,” said Del. “Many bars had policies in place that made it difficult for people of color to get in. Club 219 was not one of them. In fact, we were often criticized by white privileged gays that the bar was ‘too Black.’ After awhile, it was like, you’ve got to be kidding me, we live in Milwaukee. What the hell does ‘too Black’ even mean? We’re talking 1986, 1987, 1988.”

“Club 219 broke the rules when it hired a female bartender,” said Del. “Tony specifically wanted a gay woman behind the bar, and Debi Vance made a killing when she took that job. You wouldn’t see women at other gay bars, especially in such a visible role.”

Debi’s popularity inspired Del to launch a Ms. Gay Wisconsin contest at Club 219 in November 1981. Grace Muro was selected from four contestants as the first-year champion.

“I was afraid someone else was going to start one, so I got the trademark,” said Del. “I don’t know how many happened, but we had the first one.”

Showtime at Club 219

Showtime at Club 219

Showtime at Club 219

Showtime at Club 219

High school, reunited

Del was invited to his 10th high school reunion, which wound up being a rather unexpected experience.

“They sent out this questionnaire, asking us to tell them all about ourselves,” said Del, “so I answered it honestly. I figured someone was doing research. I’m writing all these details, I’m with this man, Tony, and we’ve been together five years, and we own one of the premier gay nightclubs in Milwaukee, and I’m working as a nurse, and on and on."

"When it was time to go, I said ‘come on, Tony,’ and my friends were all excited that I was bringing him. He agreed to come for dinner. So we’re checking in, and they hand you a nametag with your yearbook photo, and this reunion book. Inside is everyone’s name, in alphabetical order, and all this information I gave them. I thought it was going to be kept private, but no, no, it all ended up in that book.”

“So I open up the book, see what I said about myself, closed the book, and look at Tony,” said Del, “and we had this Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz moment. He asked, ‘what, what?’ and I said ‘oh, nothing.’ But as we walked into the hall, and took our seats with the rest of Section 15, there was dead silence. And he’s asking ‘what’s going on here, Del’ and I keep saying ‘nothing.’ And I’m sitting there just smirking like Lucy.”

“After dinner, five people came up to me from drama class, and one of them said thank you, because he was gay too,” said Del. “But that didn’t stop the jocks. I was walking around with my friend Gregg, and this football guy comes up behind us and pours a beer over Gregg’s head, saying ‘fucking fags.’ I’m totally aghast, and Gregg turns around saying ‘I’m not even the one who wrote it!’ I confronted the guy, and said ‘you were the people calling me a fag in high school, and I have just proven that what you thought was correct.’ He just walked away."

"People admonished him for his behavior, and eventually he apologized, but who thought they had the right to do that kind of thing?”

Family ties

As another reinvention, Club 219 introduced male go-go dancers, including The Male Factor.

“I was actually part of the group,” said Del, “and Bobby Rivers highlighted us on one of his talk shows. We were doing a Deer Hunter Widow’s Show at the Park Avenue over Thanksgiving Weekend, and a local video crew was coming in to film this for TV.

“I had to tell my mother that I was going to be on the show, because there was a real risk she would turn it on and see me. So, I called and told her, and she asked, ‘you got your nursing degree and THIS is what you’re doing with it?’ I reminded her that I was a nurse, but as a bartender and dancer at a gay bar I was making more money than nursing. And she said, ‘that’s ok.’ But all of a sudden, she says ‘you’re not one of THEM, are you?’”

“I didn’t know how to respond, because it’s very difficult for me to lie,” said Del. “There was a silence on the phone. And I told her, ‘I am, and I am with somebody, and we own a bar together.’ My mother said, ‘Delbert, how could you?’”

“That’s how the conversation started, and it went on back and forth for weeks,” said Del. “There was talk about doctors and therapists. I stopped talking to my mother for awhile. One day, my father came to my apartment and said ‘call your mother, she’s been crying.’ He also told me I would always be welcome, but not to bring my friends to my brother’s house.”

For years, Del would visit with his family, and then excuse himself to spend holidays with the Tony’s family. Tony specifically told his family that they would accept Del, no matter what. The Canfora’s spoke Sicilian around the dinner table, which left Del as the only one outside the conversation.

“I was very open with my parents where I was going, and after about two years of this, my mother finally says, ‘I don’t understand why you don’t just bring Tony here for the holidays,” said Del. “We were washing dishes, because these conversations always occur when you’re washing dishes with your mother, and I just looked at her with disbelief. She told me, don’t bring anybody, and now she’s like why aren’t you bringing him. Are you embarrassed of him? How do you respond to that?”

“So, after that, he started coming over, and I felt very blessed and fortunate. We went on vacations with my parents, and eventually, we even went to the Sicilian town that Tony came from.”

Del is proud that they ran their business as a family. Neither he nor Tony had children of their own, so they treated their employees well.

“We were the parents and our employees were our kids,” said Del. “That was our philosophy. Some of our employees had been literally disowned by their parents. So they needed some normalcy at the holidays. We realized the importance of that. We realized their need for family.”

Club 219 Girls

Club 219 Girls

Dahmer

Seeing Club 219 depicted in the Dahmer docuseries on Netflix was “seriously surreal” for Del.

“I’m not sure how this show even got made,” said Del, “because they didn’t talk to the bar owners. They didn’t talk to the bar employees. They barely spoke to the victims’ families. His victims were much younger than they were depicted. It’s a heavily fictionalized, irresponsible production. It’s almost mythological.”

Del had a confession to share: he actually served Jeffrey Dahmer, more than once.

“He was the cheap fuck customer that every bartender dreads,” said Del. “He would come in on Saturday and Sunday afternoons, drink tap beer, and hustle older men for drinks. He would be at C’est La Vie all the time, but for some reason, Netflix focused only on Club 219. He was a very annoying, high maintenance customer who pissed me off in the worst way.”

“A lot of people said they wouldn’t watch the Netflix show, and I understand why. We’ve already lived through this, and we keep living through it every time another movie comes out. Enough’s enough. There’s nothing left to say about it.”

End of an era

Club 219, and Milwaukee nightlife, continued to evolve. They decided to launch Sunday night drag shows – which was a direct challenge to ruling dance club Park Avenue.

“Park Avenue was not a gay bar, but they had a controversial ‘gay night’ on Sundays that divided the community,” said Del. “Many felt they were taking money from the gay bars, others felt the gay bars weren’t offering anything competitive. So we started doing drag shows early evenings, so we could get them before they went to Park Avenue.”

More nightspots opened, competition increased significantly, and reinventing Club 219 became a full-time job. Del and Tony took a “time out” to assess the future of Club 219 – realizing it was exhausting, frustrating, and increasingly expensive to operate.

“We needed to talk about money, because we needed to reinvest,” said Del, “and for the first time, we started thinking about how much longer we wanted to be doing this. Eight years is a long time to run a nightclub. Do we really want to keep doing this?”

After working for the Canfora family bakery, Tony had worked for Crestwood Bakery, and when it went out of business, he and Del bought a bakery in West Allis together. He wanted a bakery of his own. They maintained ownership of the Club 219 building, but sought a new owner for the business.

Bobby Lyons, who ran Club 94 in Kenosha, stepped forward to operate the business, and brought in Chuck Cicirello (formerly of The Factory) to manage Club 219. And then, all of a sudden, Bobby stepped out and left Chuck as the name on the lease. Chuck promised a grand remodel of Club 219, but it never happened, with one major exception.

“When it was Circus, the bar was in the middle of the room,” said Del, “but Robert and Tony wanted it up against the wall to create more traffic flow. When Chuck came in, he wanted a circular bar like he had at the Factory. He wanted people to be able to see each other across the bar. So, he moved it back to the center, which made it hard to move around the bar on busy nights, and hard to move from upstairs to downstairs. Oddly enough, this decision would later come back to haunt him.”

“Chuck was Chuck,” said Del. “He never paid his bills. Literally. He was listing Club 219 as his residence, and would run out winter moratoriums for electric and gas to prevent disconnection. When the moratorium ended, he stopped paying rent so he could pay his energy bills. He couldn’t get the money in fast enough, and one weekend, the bar was closed because there wasn’t any power. God rest his soul!”

The money wasn’t coming in from Club 219, so Del found himself working overtime and trying to support the household. Eventually, Del and Tony decided to sell the building. The new owner wasn’t ready to evict Chuck for not paying his rent, because he needed the tavern license. When he tried to renovate the bar, the new owner was required to get a new building permit, because some of the final “remodeling” of Club 219 was not up to code. Bringing the property up to code was more expensive than the new owner anticipated.

Club 219 closed forever in October 2005 and its contents were sold at auction.

“It was sad, it really was,” said Del, “but at the same time, we had a really good run for Milwaukee. Tony and I had a great ride.”

Going, going, gone

219 was the first domino to fall in a long series of gay bar closings. Between 2005 and 2020, nearly 40% of the gay bars in America closed down. How did that feel for someone who was there at the beginning?

“Yes, it was sad, but there are so many reasons it made sense,” said Del. “These bars opened where they did, when they did, to serve a fringe community. But now, it was 30-35 years later, and the neighborhood was gentrifying, the real estate increasing in value, and those owners were all retirement age or older. A perfect storm came to Walker’s Point, and within a few years, the bars were gone.”

“Sure, you can go anywhere you want now, but can you really be yourself when you get there? I think back to Park Avenue, which wanted to be Milwaukee’s Studio 54, but only allowed gay men to dance together on Sundays. It was frowned upon any other night of the week. That was an experience you’d only have at Park Avenue back then; now, that’s how the whole world works. You can go places, and express yourself, but will you be entirely comfortable and welcome doing that?”

“I also worry that our community has become too scattered to the wind,” said Del. “There’s not just one area, or those guaranteed spaces, where you can find your community, your commonality, your people, anymore. The bars were the place where you could have honest conversations. Now, that’s all become diffused. Socializing happens online on apps, not in person."

"How do you define yourself -- when you’re not together in real life anywhere anymore? How do you unite against a common cause?”

“If I’m going out, I want something a little more intimate now,” said Del. “I often find myself at Kruz, which has that sort of tenor I’ve always liked, going back to the Wreck Room. It resonates with me because it feels so familiar.”

“Would I do it all over again? Yes. I would love to do it all over again, as long as I could turn the clock all the way back to 1981. I wouldn’t want to be a business owner in today’s business climate. I’ve been out to places, and nightlife is not what it used to be. Electronic devices have really had a negative impact on human interaction."

"If I ran a nightclub, I’d make people leave their devices at the door. If you’re going to experience this place, then you’re going to experience it, and become part of it. And the only way to do that is to get rid of the devices. It was a beautiful time when we didn’t have them.”

However, history has a way of catching up with Del – at the most unexpected moments.

“Someone came up to me at work, a couple of years ago, and showed me this photo from Club 219,” he said. “We had some type of leather event in the lower level, and I wound up entering the International Man of Leather competition. And there I was, wearing a yellow wrestling singlet in this sea of black leather. And I thought, wow, what was I thinking, and how did I pull that off? And who took this picture? It wasn’t like people brought cameras to Club 219, or anywhere, back then.”

“I have no idea where he found the picture, but it was definitely me. The picture reminded me things were so very different then – more different than I even realized. It was wild.”

Del sings with the Bel Canto Chorus, an independent local choir dedicated to lifelong learning and thriving communities. He was a home health coordinator before working at the Veterans Administration Hospital for 34 years. Thanks to a generous tuition reimbursement program, he decided to pursue his master’s degree in nursing. Since then, he’s taught at Marquette University, Herzing University, and Briggs and Stratton.

After being diagnosed and treated for prostate cancer, Del has a public service statement for other gay men.

“We really, really need to be talking about prostate cancer,” said Del. “We need to keep an eye our PSA levels. Insurance companies will say this test is only needed every other year, because they don’t want to pay for it, but I believe it should be done a yearly basis. Especially if you have a family history of prostate cancer. You have to advocate for your own health care.”

Closing thoughts

“I was talking to someone recently, and going through all this history, and they said ‘wow, you need to write this stuff down,’ and I was like ‘you know, you’re right.”

“Looking back on my life, I am very grateful to be so very blessed,” said Del. “I have family. I was with Tony for 38 years. I still go to Sicily to visit his family. These visits are extremely therapeutic for me."

"I met one of his great nephews when he was a seven-year-old child. I remember him crying when we left Sicily, because he made such an impression on him. He went to college for nursing because I was a nurse. Today, he’s an ICU nurse living in London.”

“There’s always going to be bad moments, but you have to find the blessings in those moments.”

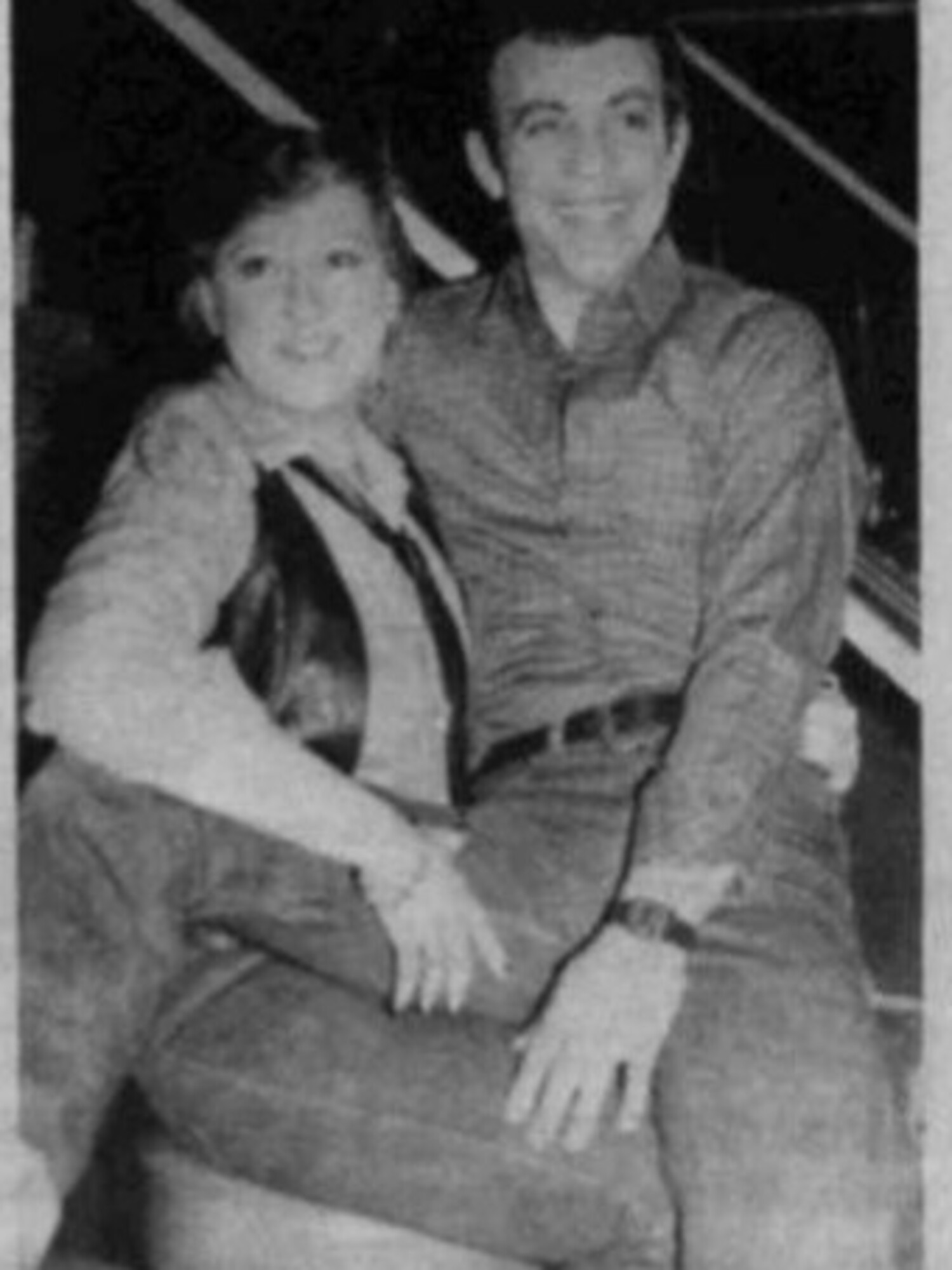

In memory of Tony Canfora (1939-2019)

In memory of Tony Canfora (1939-2019)

recent blog posts

December 17, 2025 | Michail Takach

December 16, 2025 | Michail Takach

December 01, 2025 | Dan Fons

The concept for this web site was envisioned by Don Schwamb in 2003, and over the next 15 years, he was the sole researcher, programmer and primary contributor, bearing all costs for hosting the web site personally.