Camille Farrington & Vicki Shaffer: standing up for students

“We changed lives. We saved lives. And that’s what I’m most proud of.”

Did you know? When the New York City Police raided Stonewall, they detained underage customers in the bar’s coat room to "teach them a lesson."

Locking queer youth in the closet didn’t work out so well at Stonewall, nor at any point in American history before or since.

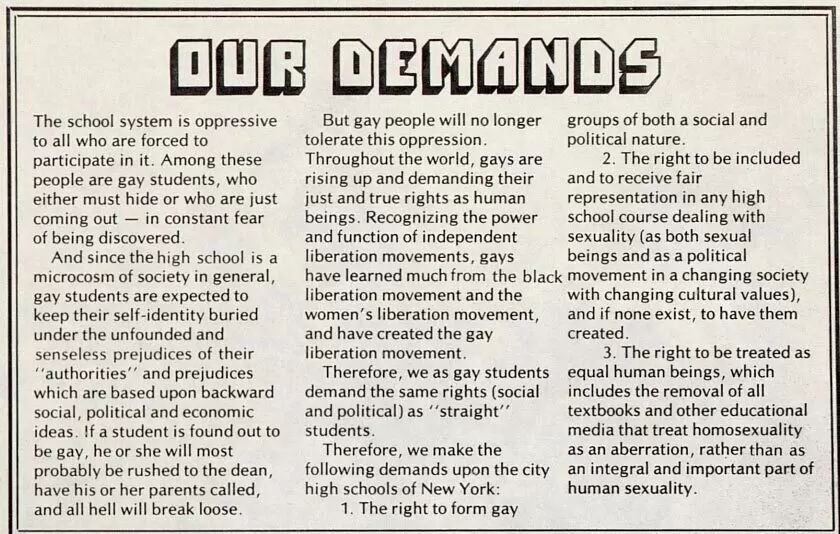

With increasing access to supportive resources, inclusive education, and accepting families, LGBTQ youth have been coming out younger, healthier, and more confidently with each new generation. Unfortunately, our nation’s schools weren’t always built to support everyone. Queer students have historically faced bullying, harassment, and violence from classmates, and even worse, silencing and exclusion from school employees.

Gay-straight alliances are such a recent invention that millennials were the first generation to benefit from them. Generation X relied on “teen clubs” – legalized by Wisconsin’s drinking age change of 1986 – to navigate their emerging identities and communities. By 1996, most of Wisconsin’s teen clubs were already gone, leaving a vacuum in their wake.

Today, over 260 gay-straight alliances (also known as gender & sexuality alliances) are creating safety, belonging, and connection throughout Wisconsin’s 421 school districts. But it wasn’t long ago that these groups were seen as controversial – despite their ongoing contributions to compassion, empathy, acceptance, and social good.

Here’s the story of how two determined Wisconsin educators, seeking a better world for all, took a stand so that LGBTQ students could be seen.

Vicki realized this was just the tip of the iceberg. If opposing homophobia couldn’t be discussed in the classroom, what message did that send to gay students facing homophobia in the hallways?

“Martha Popp was on staff at Middleton High School,” said Vicki. “She was very visible and out at work and very committed to the idea of safe and inclusive schools. So, we went to the [GLSEN] conference together and connected with a bunch of other people. Everything was coming together.”

And then Vicki and Martha had a life-changing moment: they went to see Jamie Nabozny speak.

“We knew we wanted to do something, but then we heard this young man speak,” said Vicki.

“His case had not yet been settled, and the outcome was still very uncertain. We said, ‘if he can do this after everything he’s been through… screw it, we’re going back, and we are making this happen!’”

Two things happened when they got home. First, Martha and Vicki connected with adult gay and lesbian groups around Wisconsin. Second, they met with their colleagues and announced they were starting a Gay-Straight Alliance at Middleton High School and a Madison-area chapter of GLSEN.

“Having the GLSEN chapter was really crucial to getting GSAs started in the area,” said Vicki. “I’m almost positive it was spring 1995 that we put up our first flyers.”

There was just one problem: while the administration was mostly supportive, the principal of the high school was not.

“My school district paid for me to attend the GLSEN conference, although I can tell you that my principal was not happy,” said Vicki. “So, when we came back, and I said we are going to start a GSA, she was even less happy!”

“She stopped me in the hallway one day – and I will never forget this – and asked if we were going to be talking about sex in the GSA. I am kind of a smart ass, so I almost said ‘well, of course, why wouldn’t we?’ but thank God there was a filter on my brain that day. I realized she was serious, and I said, ‘no, no, that’s not the goal of the GSA.”

While there were people like the principal who were not supportive, they were definitely in the minority. The number of allies far outweighed the naysayers.

“There was a period of time where four lesbians worked in the English Department together. We used to call ourselves the Lesbian Avengers and do the Charlie’s Angels pose for photos.”

Spark, meet blaze

Today, Camille Farrington is a senior advisor to the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research. In 1996, she was teaching at Oregon High School in Dane County.

“Some of the students had friends in Middleton, and said, ‘hey, look at what they’re doing for gay kids, let’s do it here,” said Camille.

“I was a married straight woman with kids, and I always recognized the privilege of that. They needed a faculty advisor for the Gay-Straight Alliance, and it was a no-brainer for me to take that role. Nobody was going to come after me or my job. That wasn’t true of my gay and lesbian colleagues at the time. There were no real legal protections for them. I knew that I could support my closeted co-workers by doing this.”

On July 31, 1996, Judge Jesse Eschbach of the 7th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals decreed that the Ashland School District had violated Jamie Nabozny’s Constitutional rights. Nabozny was awarded $962,000 in damages. A year later, the U.S. Department of Education clarified that Title IX protections applied to gay and lesbian students.

These actions sent an undeniable message to school administrators across the country: yes, bullying is your problem – and you will be held accountable for ignoring it.

“Things really started happening,” said Camille. “The Oregon High School administration realized they, too, could be sued for not providing a safe space for gay students. It was not in their best interest to say no, we won’t allow a GSA, or no, we’re not going to support you.”

Within four or five months, Wisconsin’s GSA movement went from zero to three. The next school to launch was Memorial High School (now known as Vel Phillips Memorial High School.)

“Judy Gump was their advisor,” said Vicki, “and there was a time where it was just Middleton, Oregon, and Memorial. We were the only schools in the area with GSAs. And Camille and Judy and I would be like, ‘what should we do with them? I don’t know what we should do?’”

GLSEN Lock-In with Senator Tammy Baldwin

GLSEN Lock-In with Senator Tammy Baldwin

"The internet wasn’t quite as accessible at the time, so they’d call around until they found someone who could help them do this.”

“Eventually, they’d get to Vicki,” she laughed.

“GLSEN ran out of people’s homes for the first 3-4 years,” said Vicki.

“We took turns alternating home phone numbers, and it was mine for a while. Kids would talk to other kids, and somehow the GLSEN number got out. We’d get adults calling, saying ‘this kid wants to start a GSA’ and GLSEN became a sort of support hotline. I always laughed, because people would think they were calling an office, and they’d get my home answering machine message.”

Connecting with community

Ryan Mueller started his freshman year in 1996.

"Middle school was a personal hell for kids back then," said Ryan, "you heard a lot of 'that's so gay,' 'you're a fag,' things like that. Nobody really addressed it -- and that was kind of sad."

"The GSA was just getting started when I arrived at Middleton High School, and its impact was visible to me right away. Teachers would say, 'that's not acceptable' or 'that's not tolerated in my classroom' when they heard those words."

Ryan admits he wasn't "necessarily a great student," having been expelled from school in eighth grade and homeschooled by a tutor for several years.

"When I got to high school, I didn't really have many friends," said Ryan. "I already felt like an outcast before I realized something was different about me. I wasn't quite sure what it was, until I met another student who was somewhat flamboyant, somewhat effeminate."

"He told me that he was gay, and I was like, OK. But then he asked me to come to the GSA, and I thought, what the hell is that -- and do I get out of class for it?"

"I had ulterior motives for joining," he laughed. "But I soon learned how important this group was going to be for me."

Ryan remembers feeling inspired by the group's mission statement: to create a world that wouldn't need GSAs, because everyone would be equal and accepted.

Unfortunately, he also remembers pushback from parents and students. Some parents feared there would be too much sex talk, which they felt was inappropriate for school. A few even requested to chaperone and observe the GSA meetings.

"It wasn't the cool club to be in," said Ryan. "It wasn't hush hush by any means, but kids were not rushing to join the GSA. I think part of the reason it took off was celebrities started coming out: Ellen DeGeneres, Melissa Etheridge."

"They made it OK to be the way we were. We're not weird, we're not strange, we're just normal people living our lives. Once people started to see that, things started to change."

Ryan was fortunate to have supportive parents who accepted and understood his needs.

"From the jump, they told me that they loved me no matter what," he said. "They just wanted me to be happy."

When one of his friends was kicked out of his home for being gay, Ryan's parents welcomed him into theirs.

"They felt he'd done nothing wrong, and that his parents should be ashamed of themselves," said Ryan.

"They let him stay with us, in our tiny little house, until he could figure something out. They saw the value of supporting kids where they were at. I think, by doing so, they inspired me to do the same for the next group of kids like him."

Overcoming the critics

“It was really connecting with Vicki that catalyzed some of the statewide work,” said Camille. “But we had a really big local problem to resolve first.”

The Westboro Baptist Church was canvassing Madison, putting up billboards, leafleting schools, and spewing hatred in the local media. In addition, Pastor Ralph Ovadal of Pilgrims Covenant Church was raising hell against Madison’s queer community.

“We were getting a lot of push back, and now Ovadal and his flock were coming to protest,” said Vicki.

“Club rosters – and member names – are publicly available. We were already concerned with how gay kids were being treated, and now GSA members were being targeted directly. So, we listed the GSA as a student assistance program and not a club, which protected the students against harm.”

“We had a superintendent at the time who was really supportive and really cared,” said Vicki, “and so was our teachers’ union. Everyone came out of the woodwork – teachers, parents, students – to encourage what we were doing. Yes, there were some people who weren’t thrilled about the GSA, but over time, their voices became less and less loud.”

“There was a lot happening, at this moment in time, and that was pushing the topic higher and higher in the collective consciousness, on all sides,” said Camille.

One challenge the founders never met: accusations of “grooming” or “recruiting” children.

“I have to say, we never really heard that,” said Vicki. “Sure, some of that ended up in the literature that Ovadal was spreading. One of our teachers walked into her classroom one day, and there was really gross propaganda on her desk. But nobody ever dared to say it to our faces.”

“As part of the curriculum battle, we had to attend a review committee meeting,” said Vicki. “That was a horrible process. The narrative was always ‘this isn’t appropriate, that’s not appropriate,’ but they didn’t use words like grooming. It just wasn’t a word they were throwing around then.”

“We didn’t hear pushback about recruiting,” said Camille, “but we did hear this notion that ‘young people don’t really know their sexuality, they’d grow out of it if you weren’t influencing and encouraging them.’ I don’t think they had found the word ‘recruiting’ yet.”

“We weren’t recruiting anyone, though, the students came to us as volunteers, and I’d like to think we saved a lot of lives along the way,” said Camille.

"As an adult, I look back and want to believe it wasn't me that people didn't like," said Ryan, "but the fact that I was OK living in my truth. They didn't know how to do that -- and they were jealous that I did. Instead of wishing they could be like me, they needed to put me down to make themselves feel better. It didn't stop me. I was very rah rah about myself!"

"I think one of the coolest things that happened was that teachers began coming out and being open," said Ryan. "They were like, hey, if these 16- and 17-year-olds can be out and happy, I should be able to do the same. That was really, really, really cool."

In April 2000, 18 students from the Oregon and Middleton GSAs traveled 23 hours by bus to Washington D.C. for a national rally, museum tours, and a visit with Representative Tammy Baldwin. Chaperoned by 11 adults, including teachers and parents, the trip was inspired by the Millennium March on Washington for Equality, which sought activism on hate-crime legislation, marriage equality, and voter engagement for the 2000 elections.

Their journey was covered by the Washington Post, who noted "this Wisconsin group is proof of just how far the gay rights movement has come."

"To this day, that Washington D.C. trip is one of my favorite lifetime experiences," said Ryan. "Seeing that many gay people in one place was life-changing. I still remember seeing a sign that said, 'If God hates gays, why isn't it raining?' Because it was one of the most beautiful, blue sky, sunshine days ever. I saw that as a message that I was going to be okay."

Bending towards justice

Three decades later, the GSAs at Middleton and Oregon High Schools are still operating.

It's hard to believe, but the students who attended those first GSA meetings in 1995 are now in their mid-40s.

“It’s baffling,’ said Camille. “I know it baffles me all the time.”

As GSAs have shifted from a “gay-straight” focus towards gender and sexuality, the role of a GSA administrator has changed tremendously. Transgender students, in particular, are in need of specialized and competent support today.

“It was probably 2010 before I had my first student seeking support with gender identity,” said Vicki. “This was not something we were prepared to support in 1996. In reflection, our approach was pretty basic: ‘gay and lesbian people exist in the world.’ It was all about the basics of making it OK for kids to identify as gay and lesbian.”

“Trans experience was not widely understood when I lived in Madison,” said Camille. “It was not a conversation we were having at the time with students, parents, or teachers.”

"When I was in high school, everyone referred to the GLB community," said Ryan, who identifies as a trans man today. "There weren't any additional letters, and queer was seen as a very bad word. I'm 43 now, and I still cringe when I hear queer, because of how negative that word used to be. Trans was not even talked about back then. There was nobody who was out. I remember hearing Cher's child was transitioning, and I was long out of high school by then.

"If I had the words to describe who I was in high school -- that I was trans, and not 'just gay' -- life would have been very different for me. I'm glad kids are able to define themselves and express who they are."

"Society evolves, language evolves, people evolve," said Ryan. "It's wonderful to know GSAs have evolved with them. Nowadays, when I talk to my godchild about the GSA, they're like huh. Because nowadays, kids can do all these things we would never have dreamed of -- i mean, taking a same-sex partner to Prom! -- and it's no big deal for anyone. I'm grateful things are more accessible for them."

Camille changed jobs and left Madison in 2000.

Martha Popp passed away in August 2023 at age 77. She was celebrated for co-founding GLSEN of South Central Wisconsin, organizing the Safe Zone program, establishing the Week of Respect, and raising awareness of the Day of Silence. She is also remembered for her groundbreaking role in Madison’s Domestic Partner Ordinance. She was named 1997 Woman of the Year by The United and a 2001 Distinguished Alumna Award winner by the University of Wisconsin. Martha and her wife Alix were married in May 2010. They spent 43 years together, raising two children of their own, while fighting for every Wisconsin student’s right to a safe school.

Vicki retired at the end of the 2021-2022 school year.

“I’d been teaching at a charter school, where we could push the envelope more than other schools,” said Vicki. “For the past few years, they’ve offered a course on LGBTQ history, and they asked me to come and speak about the history of Middleton. This was at the end of my teaching career, and we had students in the room representing the whole spectrum of the LGBT community."

"These kids knew about me, my wife, and my career. And you just can’t fathom what that was like. Early in my career, I would never have said, ‘my wife and I did this.' This just proved to me how students today can push boundaries and explore identities in ways we couldn’t have conceived in the mid-1990s.”

“I know we’ve changed lives,” said Vicki. “One of our students became a teacher and became the Gay-Straight Alliance advisor 15 years after high school. She still talks about what a difference we made in her life, because we were the strong female role models she needed. I know that we validated them. I know we told them, ‘You deserve a really good life.’

“Our social worker at Middleton High School once shared a story I will never forget,” said Vicki. “A boy came into her office and disclosed that he was gay. But he said, I could never go to a GSA meeting, but just knowing it’s there has made all the difference.’ I will always remember that story. Because of us, he knew he was not alone. I’m sure there were a lot of students like him, struggling to come out for themselves. They knew it wasn’t safe to do but knowing that group was there made them feel better.”

“I know we changed lives -- I know we saved lives, too. And that’s what I’m most proud of."

"These teachers absolutely saved lives," said Ryan. "So many gay students felt like they couldn't endure their lives. They were overwhelmed and found it hard just to continue day by day. And they'd come to GSA, where adults would remind them they are OK, that nothing was wrong with them, that you were accepted where you were at. That absolutely saved lives."

Closing thoughts

Nearly 30 years after they founded Wisconsin’s first GSAs, Vicki and Camille reflect on what students are facing today.

“The current generation of students feels so different,” said Camille. “I think it’s because they grew up in a much more accepting world. They’ve had a lot of role models showing them they don’t have to be quiet. They’ve had a lot of opportunities to express themselves for who they are.”

“Now, they’re seeing intolerance on the rise. The message it sends is that you are not OK, and in fact, we’re going to bring the full forces of government against you. That’s terrifying for anyone to feel that way. But I don’t think this generation is going to stand for it”

“I’ve tried to hang on to one thing as this situation has escalated,” said Camille. “Our country is notorious for backlashing against any group that gets rights. If you look at our history, this has been the swing, and we always swing back harder."

"I try to take the long view, yes, that’s the beautiful thing about teaching. There are always cycles of things in history and literature. There were many moments throughout history where life looked pretty bleak, and there was no way to imagine a better future. But better times always followed the darkest moments. Always. I do try to hold onto that long-term faith in humanity.

“But this is an ugly chapter, that’s for damn sure.”

“Oh, it’s real sad out there,” said Camille. “One of the only reasons I stay on Facebook is to stay in touch with my former students. Many of them were GSA members.”

“Right now, they’re out there being righteous in the face of this mess.”

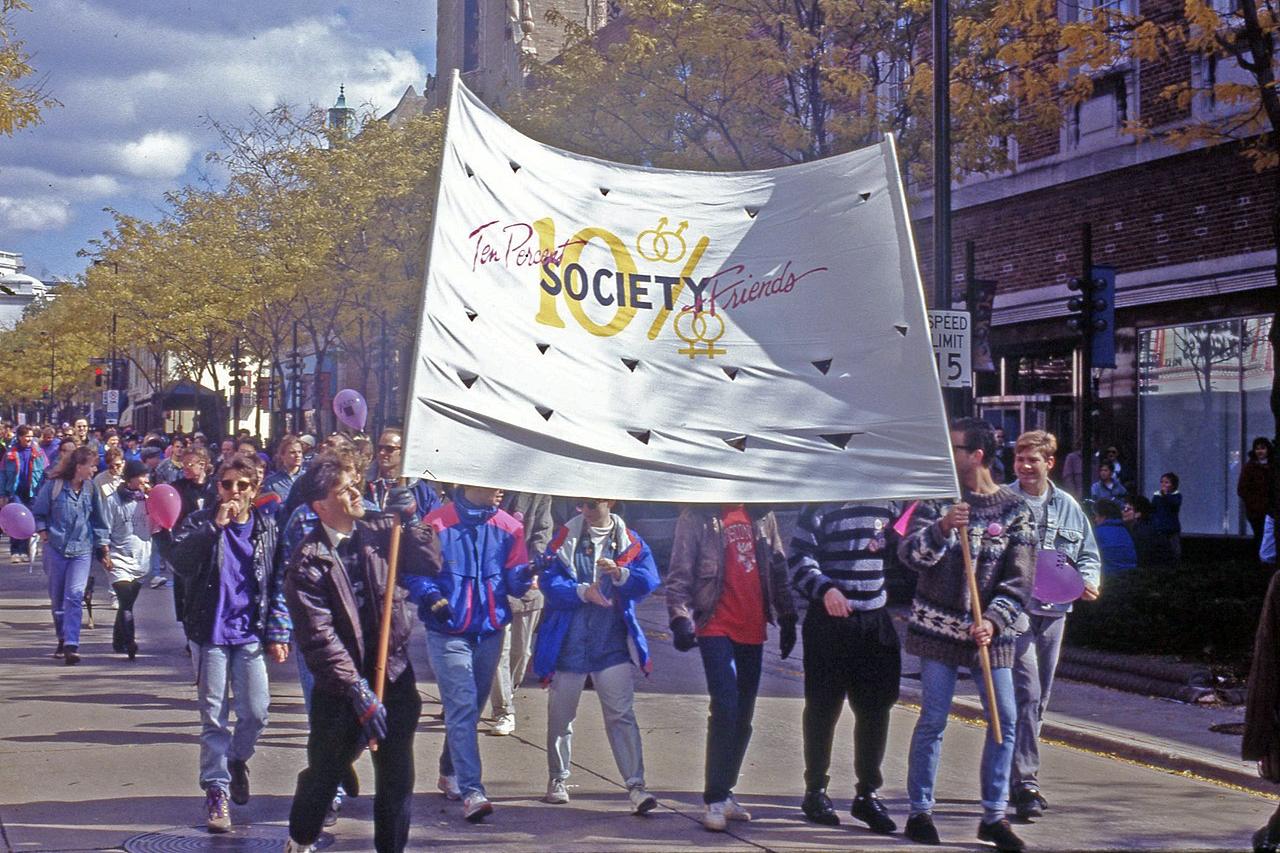

Madison Pride, 2000

Madison Pride, 2000

recent blog posts

March 31, 2025 | Amy Luettgen

March 29, 2025 | Michail Takach

March 22, 2025 | Michail Takach

The concept for this web site was envisioned by Don Schwamb in 2003, and over the next 15 years, he was the sole researcher, programmer and primary contributor, bearing all costs for hosting the web site personally.