Annie Hindle: America's first drag king

“I saw a future for myself as a queer person in Madison.”

In antebellum America, there were twice as many male roles as female roles at any given time. Female performers were expected to be attractive, while docile and subservient. Actresses were expected to be objects of beauty first, and morally upright second. They were not allowed to perform comedy – especially off-color or racy jokes.

For this reason, classical theater still cast men in a surprising number of female dramatic roles, especially roles that were intended to be comical or satirical. In other words, female impersonators were more highly valued (and more highly paid) by most American theater companies than female actresses.

Annie Hindle changed everything. She was the first male impersonator (or “drag king”) to appear on the variety stage. Only days after arriving from London in August 1868, she was making headlines and hoopla for herself in New York City. Within a few years, male impersonators were among the most highly paid variety performers in America.

Annie was determined to succeed in American theater – at any price. And her timing was perfect, because the American theater scene was booming, and hungry for fresh new acts. No longer limited to New York, proper theater companies set up shops up and down the Eastern Seaboard, across the Midwest, and along the river cities of the South. Most major cities had a reputable music hall by the 1870s, elevating these shows above the saloon trade. Safe and reliable train lines connected these cities, making it possible for troupes to go on regional or national tours.

There was just one problem: Annie was a solo act and a single female traveler. It wasn’t entirely safe for women, even a masculine woman, to venture the frontier. Although very few, if any male impersonators married men, Annie married traveling musician Charles Vivian shortly after her first tour. Vivian was one of the founders of the Grand Order of Elks and quite well-respected in his craft.

However, this was a marriage of convenience and nothing more.

Vivian said the marriage lasted just one night. Hindle said it failed in less than six weeks. She told the New York Sun that “he lived with me…long enough to black both my eyes and otherwise mark me.” The couple quickly separated, and the scandal damaged Vivian’s career. Researchers believe that Hindle had Vivian blacklisted from East Coast theaters for the next four years. The couple did not reunite on stage for a full decade.

1869 was a magical year for Hindle. She was regionally famous as “the Great Hindle,” booked solid for the full season, and the one and only male impersonator working in the United States. Imitation, of course, is the greatest form of flattery – and by late summer, Ella Wesner was giving Hindle a run for her money. She was older, more experienced, and more established in the theater world. Although her early shows were billed as “A La Hindle,” Ella Wesner became as well-known as Hindle nationwide.

In August 1869, John Stetson bought Leon & Kelly’s old minstrel hall and reopened it as The Waverly. He hired Wesner and Hindle to perform in his all-star line-up, but it closed after only three weeks. Although the women shared an agent, this was the only time they ever shared a stage or a friendship.

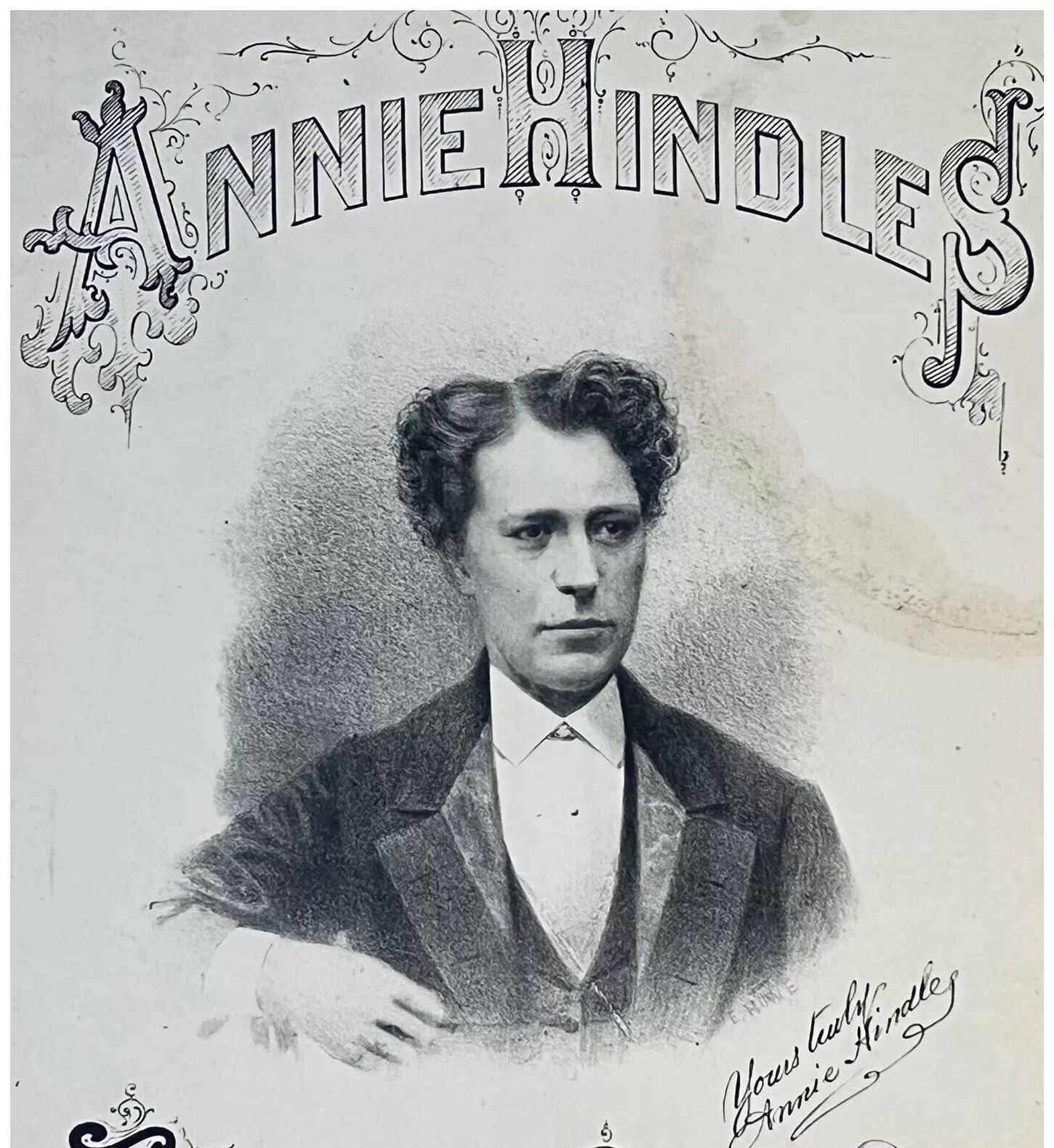

Annie Hindle show program

Annie Hindle show program

Annie Hindle Songster

Annie Hindle Songster

An imperfect gentleman

Hindle’s show was usually a series of songs, monologues, and jokes told over a 20-30 minute timeframe. Her most popular songs were about the pleasures of excessive drinking, while others celebrated the lives of ordinary men in sympathetic ways. Hindle always found a way to stir up workingman solidarity in the face of hardship and anxiety. Each song would present a different male character, involving an offstage costume change and an onstage change in voice and demeanor. Critics were harsh if each character didn’t offer a totally new experience.

At first, Hindle specialized in playing a heavy-smoking, hard-drinking, sexually adventurous stereotype of the everyday workingman. She rarely discussed work, though, because her “character” was all about being a man of leisure. She poked fun at middle-class reformers as hypocrites trying to ruin her fun. Over time her act evolved to the “man-about-town,” who was a clueless upper-class man rich in money but starved for real-world experience. The character could afford the finest fashions, wine, and cigars, but lacked the life skills to survive in urban America. Some in the audience found them ridiculous, while others envied their comforts.

Later, Hindle changed her act to represent the “fop,” “dandy,” or “dude,” or a delicate and effeminate man interested in fashion, elegance and extravagance. The “dude” was a product of toxic masculinity: Hindle’s rendition of upper-class men made the working-class audience feel more confident in their manliness. At the same time, she offered her audiences sympathetic advice about courting women, which was not a conversation most men of the era had with each other.

The ”dude” – an urban man unfamiliar with life outside the city – was both a reaction to ill-prepared East Coast men coming to the Wild West and hostility to upper classes thriving while the workingman suffered. There’s also a bit of a homophobic vibe to the character’ popularity, and it’s possible big-city audiences recognized elements of a queer subculture that was already visible. Either way, Hindle stirred up something in her audiences that loved to hate it.

Womanizing in a man’s world

In 1875, Hindle became the manager of the Grand Central Varieties of Cincinnati, a role not usually available to women at the time. Even during the Long Depression, Hindle and Wesner were very highly paid, and often out-earning their male co-stars at $100-$150 per week. This made it possible for them to thrive independently without male husbands or managers.

Annie Hindle’s poetry appeared in the New York Clipper throughout the 1870s, and it was often quite revealing. Sixteen poems describing love and loss – written about females in a female voice – seemed to send secret messages to an unrequited same-sex lover. The poetry confirms long-standing suspicions that Annie Hindle’s primary romantic interests were women.

Charles Vivian remarried after their separation, although the couple had never divorced, and Annie Hindle certainly had no need for a divorce either. Instead, she became a runaway groom – of a sort.

Researchers have discovered multiple marriage records for Hindle under the alias “Charles,” such as “his” December 1868 marriage to dancer Nellie Howard in Baltimore, and “his” November 1870 marriage to Blanche DuVere in Washington, DC. DuVere later reinvented herself as male impersonator Blanche Selwyn.

In September 1878, she married performer William W. Long, although the couple never actually lived together. Soon afterwards, the New York Clipper posted an announcement that Miss Augusta Gerschner was suing Annie Hindle for jewelry pawned for Hindle’s financial benefit. The column doesn’t specifically explain the relationship between the women, but it seems it was more than financial.

Billing herself as the “King of Fashion,” Hindle joined May Fisk’s Blonde Burlesque troupe in 1878, but the show was banned for “indecent content.” She toured variety houses from the Midwest to Cuba throughout the next few years. However, Ann Hindle’s death in March 1883 deeply affected Annie, as she found herself alone for the first time. She chose to chase headlines with gimmicks and publicity stunts, claiming to offer $10,000 to anyone who could solve the mystery of “whether She is He, or He is She, the Greatest Male Impersonator Living.”

In 1886, she married her tailor Annie Ryan in a Grand Rapids wedding ceremony conducted by a Baptist minister. Technically a bigamist twice over, Hindle was chased by local reporters until she “confessed” that she was a man all along. On June 7, 1886, the Grand Rapids Telegram-Herald ran an expose claiming Hindle was a man, had married Charles Vivian illegally, and had faked her entire stage act since day one.

Somehow, the scandal quietly blew over. Newspapers outside Grand Rapids simply reported that Annie Hindle, under the name Charles Hindle, married Annie Ryan, who has been traveling with him or her as a maid for five years. They left immediately for Cleveland.” Gossip about Hindle’s dalliances with her co-stars and handmaidens had percolated for years. Members of the troupe knew about the relationship and did not care. Some believe the wedding – and the gender reveal – were another one of Hindle’s publicity stunts. While there were frequent mentions of her marriage, nobody ever publicly challenged her gender again.

When the company performed in Buffalo, the local newspaper commented “there are probably few people…last evening who recognized in the character of Miss Annie Hindle, the only living woman who has a living wife. By everyone, it was agreed that her appearance was the hit…but few were aware of her remarkable history or knew of the extent to which she has carried her clever impersonation.”

For about five years, Hindle and Ryan lived together peacefully in Jersey City Heights. Hindle built them a comfortable home where "the neighbors respected them, the world did not disturb them with its gossip, and fortune was kind to them," according to The Metropolitan.

"Both dressed as woman, and lived together as man and wife, and were apparently happy," wroted the Reading Eagle. "TThe papers from that city claim they had the full respect of the community."

This was shockingly unusual for any American same-sex couple in the 1880s.

Newspaper sketch of Annie Hindle, 1897

Newspaper sketch of Annie Hindle, 1897

Hitting the skids

For the next few years, Hindle toured venues she might have shunned: dime museums, blue collar variety shows, and burlesque companies. One of her tours brought her to Jacob Litt’s Dime Museum in Milwaukee for a weeklong stay in November 1884.

“The Dime Museum continues to draw large crowds,” wrote the Milwaukee Journal on November 19. “Miss Annie Hindle, the male impersonator, has become a favorite. Her make-up as a dude is very good.”

“As a male impersonator, her sex is so concealed that one is apt to imagine that is a man who is singing,” wrote another critic.

Annie was the first male impersonator to arrive in Milwaukee, only five months after The Only Leon bedazzled audiences at Nunnemacher’s Music Hall on June 7, 1884. She wasn’t the last. Over the next few years, the city went wild for impersonators, notably Miss St. George Hussey, who took up a residency at the Grand Opera House in January 1886, and Ada Armour, who played Litt’s Theater for a spring run in 1888.

When her wife died in December 1891, she moved to Manhattan and returned to the stage almost immediately.

On June 26, 1892, she married Louise Spangehl of Troy, New York, in another Baptist wedding ceremony. Their marriage – Hindle’s fourth – was reported far and wide in national newspapers, and oddly enough, without any moral judgement. The couple met during Hindle’s local performance, but it’s not clear how they met, or if they ever actually lived together. Hindle left Troy, New York for the next show of her tour and Spangehl stayed behind. It’s possible this wedding, too, was a publicity stunt – but in the end, the headlines did very little for the twilight years of Hindle’s career.

By the 1890s, social concerns about gender roles were increasing. Fears about “mannish women” began to be as loud as complaints about effeminate men. Parents were warned against the dangers of “education and ambition” leading women to develop traits contrary to feminine nature.

“The nineteenth century has developed something between a woman and a man, called a ‘mannish woman,’” wrote one reporter. “She slaps her knees, she affects the most masculine of hats and ulsters, her language is of the stable and the boathouse, she delights in slang, she wears no gloves allowing her hands to grow red and coarse, she parts her hair on one side. Who can care for, or protect, this mannish woman?"

Despite her outspoken love for women, her scandalous affairs and marriages, and her onstage character, Annie Hindle was never accused of being a “mannish woman” nor an “invert” (a sexological term used to describe lesbians that strongly implied they were -- in today's terms -- actually transgender.)

Somehow, she always managed to separate the actor from the art in such a convincing way, audiences always understood that she was not a genetic man, didn’t want to be a man, and didn’t live her offstage life as a man. Her audience forgave her for taking multiple wives as much as they forgave her for taking multiple husbands.

By the turn of the century, Hindle and Wesner were considered “old-timers” of the stage, and no longer marketable or fashionable. In fact, reporters could be quite cruel to them.

"A strange fate has overtaken Annie Hindle...she has grown a moustache, and actually believes at time that she is a man. In male dress, she presents all the appearance of an ordinary man...[She] was originally a rather pretty girl..."

"Her voice became masculine in tone, and recently it appears that her mind has become somewhat unhinged..." wrote The Montreal Metropolitan in 1897.

As vaudeville rose in popularity, women were allowed more active stage roles unthinkable in Hindle’s time. These roles included many famous female impersonators, but male impersonators disappeared from American stages for many decades. Grace Leonard and Vesta Tilley visited Milwaukee during World War I, and Kitty Doner in the 1920s, but they were seen more as niche curiosities than an art form. Hindle was a hard act to follow.

Annie spent her final years in Ohio. She was reported to be on her deathbed in 1896 but was arrested for public intoxication in Buffalo in September 1900. She returned to a two-year stage engagement in Toledo in 1901. Her final known performance was singing at either Dayton’s Odeon Theater or Cincinnati’s Casino Theater in October 1904. After those shows, she simply disappeared.

Married six times, but never divorced, Hindle had no known children or successors of any kind. Nobody has ever been able to determine where, when or how she died, or where she was laid to rest.

For someone who lived every day of her life with a bang, she seems to have ended it with a whimper.

Postscript: Ella Wesner

On May 3, 1914, the Milwaukee Sentinel wrote, “Ella Wesner was the greatest male impersonator the stage has ever known .She was the real man of real life. For many years, Miss Wesner made a huge salary and helped to support an aged mother and sisters. Poverty overtook her, and we called upon this once famous star to see what might be done. “About how much do you require,” said I, and said she “I would like at least enough to get a haircut and a shave.”

Ella Wesner (1841-1817) died in the Bronx at age 76. She was buried in a mens suit at her request at Evergreens Cemetery in Brooklyn.

Annie Hindle marries Annie Ryan, 1886

Annie Hindle marries Annie Ryan, 1886

Annie Hindle marries Louise Spangehl, 1892

Annie Hindle marries Louise Spangehl, 1892

recent blog posts

April 21, 2025 | Michail Takach

April 06, 2025 | Michail Takach

Camille Farrington & Vicki Shaffer: standing up for students

March 31, 2025 | Amy Luettgen

The concept for this web site was envisioned by Don Schwamb in 2003, and over the next 15 years, he was the sole researcher, programmer and primary contributor, bearing all costs for hosting the web site personally.